The Journey Without

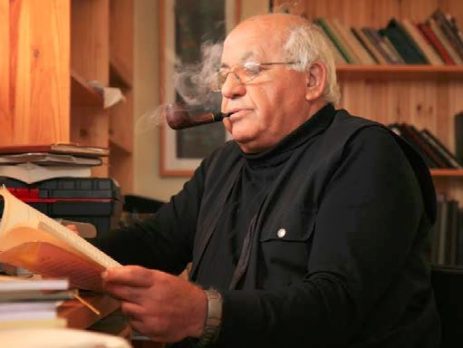

Salman Natour (1949–2016), one of the prominent Arab Palestinian intellectuals in Israel, was a writer, playwright, editor, and translator. Among his many roles, he was the editor of the cultural supplement of the daily Al-Ittihad, the editor of the monthly Al-Jadid for literature and art, and the editor of the journal Qadaya Israʾiliyya, published in Ramallah. He wrote more than thirty books and translated many works from Arabic into Hebrew and from Hebrew into Arabic. He was the director of the Israeli-Palestinian Committee of Artists and Writers against the Occupation (1986–1992) and served on the board of directors of Adalah, the legal center for Arab minority rights in Israel (2000–2006). He also served as the director of the Emil Touma Institute for Israeli and Palestinian Studies in Haifa. Salman Natour was born in Daliat al-Carmel and lived there all his life.

The Birth, Life, and Afterlife of a Text by Salman Natour

Nathalie Alyon

Sometime between 1949 and 2008, somewhere between Israel and Palestine

Salman Natour, an Arab Palestinian author from the Druze village of Daliat al-Carmel, wonders “how to begin the story between the homeland and what remains outside it? How to begin the story between the place you stand and the one that evades you?”[1]

Having grown up against the backdrop of the Israeli state that had arrived in his village nestled in the Mount Carmel hills, Natour relentlessly narrates the stories of the human beings behind the Arab-Israeli conflict. This story will not be different. Known throughout the Arab world, from Jordan to Tunisia, he is one of the most prolific and inspirational writers of the Arab Palestinian community in Israel.

2008, Ramallah

Salman Natour’s Safar ʿala safar (Journey over journey) is published in Arabic by Muʿassasat Tamer publishing house in Ramallah. In the novel Natour explores themes familiar to modern Palestinian Arab literature: memory, exile, and homeland. Yet the voyage he recounts in this book is not just a physical journey between places but also a metaphysical journey through time and memory.

It is “the story of time that has neither beginning nor end . . . the story of a man without a home and deprived of a homeland . . . the story of the Palestinian without time, without hope, and without a dream.”[2] It begins with an allegorical Palestinian hero at Ben-Gurion Airport, standing at the gates of home and exile, about to embark on a journey in search of both himself and the “other” self—the Palestinian exile—on the streets of Rome and Paris and London. Visiting these foreign stations, his narrator stops to find a glimpse of his complex identity.

2014, Jerusalem

Salman Natour, together with Yehouda Shenhav-Shaharabani and Yonatan Mendel, establishes the Translators’ Circle at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. It is a unique project in which Jewish and Palestinian literary scholars, translators, authors, and poets study and discuss the movement between Arabic and Hebrew, Arabic literature, and questions relating to translations between Arabic and Hebrew.

The Translators’ Circle suggests new norms in the field of translation from Arabic to Hebrew. First, translation is dependent on copyrights from writers. This sounds technical, but for many years it was customary to translate Arabic literature without the authors’ consent. Second, each translator enjoys the assistance of a native Arabic speaker and a native Hebrew speaker, who move back and forth between the two languages. One of the fruits of this project is Maktoob, a series of books—unique in terms of action and rationale—dedicated to the publication of Arabic literature in Hebrew.

A strong believer in the power of literature to raise and nurture humanism, Natour has already translated works by many prominent Israeli authors—including David Grossman, Amos Oz, Benjamin Tammuz, Haim Nahman Bialik, Yehuda Amihai, and Yeshayahu Leibowitz—into Arabic. Indeed, Natour’s faith in literature is rooted in the belief that living together, especially in the case of Jews and Palestinians in Israel/Palestine, could not be achieved without the acknowledgement and awareness of the experiences of the other, particularly those that hurt one the most. In an interview on Israeli television he says, “If Jews want to live in peace with Palestinians, they need to hear their stories.”[3] When the editors of Maktoob inform Natour that they would like to include one of his novels, translated into Hebrew, as one of their books, he is deeply touched.[4] He does not know and will never find out that the book will be Maktoob’s first publication.

2015, Jerusalem

Natour shares with Yonatan Mendel the idea of translating Safar ʿala safar into Hebrew, but rather than keeping it solely a novel, infusing it with sections from two of his other creations that include segments of the figurative Palestinian’s journeys traveling both to and from and within and without his homeland: Yamshun ʿala al-rih (Hebrew: Holkhim al ha-ruah, English: Walking over the wind) and Intizar (Waiting). It will describe the Palestinian traveling around and through his mythological and historical homeland as both native and foreigner. It will be “the story about the no-place, about the no-time, no-soil, and no-sky.”[5]

November 2016, Jerusalem

After months of work, Mendel sends Natour a draft of Safar ʿala safar’s new life in Hebrew. The draft includes notes by Mendel outlining the seams where he envisions the different works meet to create what will become Holekh al ha-ruah (Walking on winds).

January 13, 2016

Mendel receives Natour’s comments on the draft by e-mail. “Dear Yoni, at last,” Natour writes alongside the attachment. This electronic communication is their last correspondence.[6]

February 15, 2016, Daliat al-Carmel

Salman Natour, age 66, who was born and raised in Daliat al-Carmel and who worked there throughout his life, passes away at the Carmel hospital in Haifa

after a sudden heart attack. The translation of his new trilogy, Holekh al ha-ruah (composed of Safar ʿala safar, Yamshun ʿala al-rih, and Intizar), is far from finalized. Which sections will be included at the expense of others? In what order will the text be organized? How will the narration of a dialogue between a Palestinian and a rightwing Israeli Jew be rendered in Hebrew? With further input from Natour no longer possible, the small decisions that accumulate to create a piece of linguistic art now burden his translator.

February 15, 2017, Jerusalem

Natour’s trilogy, in its Hebrew reincarnation, is published in a rather emotional book launch at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, exactly one year after its author’s death. As Natour’s family, friends, and colleagues pay homage to his life and work, an audience filled with Jews and Palestinians, including Natour’s friends and family from his hometown, listen with utmost attention to the speakers, who greet them in Arabic and in Hebrew.

Mendel, who never imagined that the book would be published in Natour’s absence, writes about the book launch he wished for:

I pictured myself greeting Salman on the eve of the launch, seeing the warm, paternal smile in his eyes. I picture him taking his place upon the stage; he rests his glasses on his nose and begins to speak. His deep voice echoes through the hall. He talks about the most difficult things in a way that allows for true listening. He talks about humanity, about the path to shared living and a just life. He speaks about honor and about understanding and recognition of Arab culture and language, about the concerns of the poor and the need to fight oppression, about Palestinian identity and the experience of exile. His voice rises like thunder as he speaks of the nation that deserves liberation from occupation and the nation whose freedom remains shackled as long as it controls another people.[7]

September 2017

Inspired by Natour’s words, the editorial team at the Journal of Levantine Studies asks the author’s family for permission to translate into English and publish the first chapter of Holekh al ha-ruah. With their blessing, a new team of translators and editors embarks on a new journey to give this “text of exclamation points and question marks” yet another afterlife as a stand-alone piece titled “The Journey Without.”

***

As Walter Benjamin delineates in “The Task of the Translator,” a work of linguistic art enters a new stage of existence with its translation into a new language, a new culture, and a new set of readers with different historical and cultural narratives. Through the act of translation it is reborn in a new form:

Just as the manifestations of life are intimately connected with the phenomenon of life without being of importance to it, a translation issues from the original—not so much from its life as from its afterlife.[8]

The convoluted history of “The Journey Without” in its English reincarnation illustrates the independence of a text after it separates from its author’s pen. It is the second text by Natour to be translated into English.[9] As both writer and translator, Natour was painstakingly aware of the opposing prejudices of a Hebrew versus Arabic readership and did not see the act of translation as one dictated by fidelity to the original.[10] It required not only a reordering of letters but also a reconceptualizing of the delivery of an idea into a different culture. In the case of translation from Arabic to Hebrew, it was also a negotiation between two kindred cultures with conflicting narratives.

“The kinship of languages manifests itself in translations,” Benjamin writes. All suprahistorical kinship between languages consists in this: in every one of them as

a whole, one and the same thing is meant. Yet this one thing is achievable not by any single language but only by the totality of their intentions supplementing one another: the pure language.[11]

Arriving at pure language via an expression of Natour’s words in English presented difficulties in its own right: conveying a local experience to an outsider readership. Shoshana London Sappir used the Arabic original as a primary source, while Mendel’s Hebrew translation served as a blueprint. In that sense “The Journey Without” symbolizes the kinship of languages as a child born to Arabic and Hebrew parents.

In “The Journey Without” this is all we present to the international readership of JLS: an afterlife of several creations from Natour’s expansive oeuvre.

Nathalie Alyon

Notes

1 Salman Natour, Holekh al ha-ruah [Walking on winds], trans. Yonatan Mendel (Jerusalem: New World Press, 2017), 9. All translations into English are my own.

2 Ibid., 10.

3 “Hotze Yisrael” with Kobi Meidan, interview with Kobi Meidan, published December 2, 2014, accessed September 11, 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ssohNWXJXGk&t=306s.

4 Yonatan Mendel, “Aharit davar” [Epilogue], in Holekh al ha-ruah, 245.

5 Natour, Holekh al ha-ruah, 10.

6 Interview with Yonatan Mendel, August 28, 2017, Tel Aviv, Israel.

7 Mendel, “Aharit davar,” 245.

8 Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator,” in Selected Writings, Vol. 1, 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996), 254.

9 See Salman Natour, “The Chronicle of the Wrinkled-Face Sheikh,” trans. Yehouda Shenhav-Shaharabani, Granta 129: Fate, The Online Edition, Fiction, November 20, 2014, accessed September11, 2017, https://granta.com/The-Chronicle-of-the-Wrinkled-Face-Sheikh

10 In “Hashpaat ha-kore be-girsaot Holkhim al ha-ruah me-et Salman Natour,” Hamizrah Hehadash 35

(1992–93), Matityahu Peled describes how a Hebrew versus an Arabic readership influences Natour’s decisions as both author and translator of his own novel.

11 Benjamin, “The Task,” 256–257.

- + About the Author

-

Salman Natour (1949–2016), one of the prominent Arab Palestinian intellectuals in Israel, was a writer, playwright, editor, and translator. Among his many roles, he was the editor of the cultural supplement of the daily Al-Ittihad, the editor of the monthly Al-Jadid for literature and art, and the editor of the journal Qadaya Israʾiliyya, published in Ramallah. He wrote more than thirty books and translated many works from Arabic into Hebrew and from Hebrew into Arabic. He was the director of the Israeli-Palestinian Committee of Artists and Writers against the Occupation (1986–1992) and served on the board of directors of Adalah, the legal center for Arab minority rights in Israel (2000–2006). He also served as the director of the Emil Touma Institute for Israeli and Palestinian Studies in Haifa. Salman Natour was born in Daliat al-Carmel and lived there all his life.

- + Analysis

-

The Birth, Life, and Afterlife of a Text by Salman Natour

Nathalie Alyon

Sometime between 1949 and 2008, somewhere between Israel and Palestine

Salman Natour, an Arab Palestinian author from the Druze village of Daliat al-Carmel, wonders “how to begin the story between the homeland and what remains outside it? How to begin the story between the place you stand and the one that evades you?”[1]

Having grown up against the backdrop of the Israeli state that had arrived in his village nestled in the Mount Carmel hills, Natour relentlessly narrates the stories of the human beings behind the Arab-Israeli conflict. This story will not be different. Known throughout the Arab world, from Jordan to Tunisia, he is one of the most prolific and inspirational writers of the Arab Palestinian community in Israel.2008, Ramallah

Salman Natour’s Safar ʿala safar (Journey over journey) is published in Arabic by Muʿassasat Tamer publishing house in Ramallah. In the novel Natour explores themes familiar to modern Palestinian Arab literature: memory, exile, and homeland. Yet the voyage he recounts in this book is not just a physical journey between places but also a metaphysical journey through time and memory.

It is “the story of time that has neither beginning nor end . . . the story of a man without a home and deprived of a homeland . . . the story of the Palestinian without time, without hope, and without a dream.”[2] It begins with an allegorical Palestinian hero at Ben-Gurion Airport, standing at the gates of home and exile, about to embark on a journey in search of both himself and the “other” self—the Palestinian exile—on the streets of Rome and Paris and London. Visiting these foreign stations, his narrator stops to find a glimpse of his complex identity.2014, Jerusalem

Salman Natour, together with Yehouda Shenhav-Shaharabani and Yonatan Mendel, establishes the Translators’ Circle at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. It is a unique project in which Jewish and Palestinian literary scholars, translators, authors, and poets study and discuss the movement between Arabic and Hebrew, Arabic literature, and questions relating to translations between Arabic and Hebrew.

The Translators’ Circle suggests new norms in the field of translation from Arabic to Hebrew. First, translation is dependent on copyrights from writers. This sounds technical, but for many years it was customary to translate Arabic literature without the authors’ consent. Second, each translator enjoys the assistance of a native Arabic speaker and a native Hebrew speaker, who move back and forth between the two languages. One of the fruits of this project is Maktoob, a series of books—unique in terms of action and rationale—dedicated to the publication of Arabic literature in Hebrew.

A strong believer in the power of literature to raise and nurture humanism, Natour has already translated works by many prominent Israeli authors—including David Grossman, Amos Oz, Benjamin Tammuz, Haim Nahman Bialik, Yehuda Amihai, and Yeshayahu Leibowitz—into Arabic. Indeed, Natour’s faith in literature is rooted in the belief that living together, especially in the case of Jews and Palestinians in Israel/Palestine, could not be achieved without the acknowledgement and awareness of the experiences of the other, particularly those that hurt one the most. In an interview on Israeli television he says, “If Jews want to live in peace with Palestinians, they need to hear their stories.”[3] When the editors of Maktoob inform Natour that they would like to include one of his novels, translated into Hebrew, as one of their books, he is deeply touched.[4] He does not know and will never find out that the book will be Maktoob’s first publication.2015, Jerusalem

Natour shares with Yonatan Mendel the idea of translating Safar ʿala safar into Hebrew, but rather than keeping it solely a novel, infusing it with sections from two of his other creations that include segments of the figurative Palestinian’s journeys traveling both to and from and within and without his homeland: Yamshun ʿala al-rih (Hebrew: Holkhim al ha-ruah, English: Walking over the wind) and Intizar (Waiting). It will describe the Palestinian traveling around and through his mythological and historical homeland as both native and foreigner. It will be “the story about the no-place, about the no-time, no-soil, and no-sky.”[5]November 2016, Jerusalem

After months of work, Mendel sends Natour a draft of Safar ʿala safar’s new life in Hebrew. The draft includes notes by Mendel outlining the seams where he envisions the different works meet to create what will become Holekh al ha-ruah (Walking on winds).January 13, 2016

Mendel receives Natour’s comments on the draft by e-mail. “Dear Yoni, at last,” Natour writes alongside the attachment. This electronic communication is their last correspondence.[6]February 15, 2016, Daliat al-Carmel

Salman Natour, age 66, who was born and raised in Daliat al-Carmel and who worked there throughout his life, passes away at the Carmel hospital in Haifa

after a sudden heart attack. The translation of his new trilogy, Holekh al ha-ruah (composed of Safar ʿala safar, Yamshun ʿala al-rih, and Intizar), is far from finalized. Which sections will be included at the expense of others? In what order will the text be organized? How will the narration of a dialogue between a Palestinian and a rightwing Israeli Jew be rendered in Hebrew? With further input from Natour no longer possible, the small decisions that accumulate to create a piece of linguistic art now burden his translator.February 15, 2017, Jerusalem

Natour’s trilogy, in its Hebrew reincarnation, is published in a rather emotional book launch at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, exactly one year after its author’s death. As Natour’s family, friends, and colleagues pay homage to his life and work, an audience filled with Jews and Palestinians, including Natour’s friends and family from his hometown, listen with utmost attention to the speakers, who greet them in Arabic and in Hebrew.

Mendel, who never imagined that the book would be published in Natour’s absence, writes about the book launch he wished for:I pictured myself greeting Salman on the eve of the launch, seeing the warm, paternal smile in his eyes. I picture him taking his place upon the stage; he rests his glasses on his nose and begins to speak. His deep voice echoes through the hall. He talks about the most difficult things in a way that allows for true listening. He talks about humanity, about the path to shared living and a just life. He speaks about honor and about understanding and recognition of Arab culture and language, about the concerns of the poor and the need to fight oppression, about Palestinian identity and the experience of exile. His voice rises like thunder as he speaks of the nation that deserves liberation from occupation and the nation whose freedom remains shackled as long as it controls another people.[7]

September 2017

Inspired by Natour’s words, the editorial team at the Journal of Levantine Studies asks the author’s family for permission to translate into English and publish the first chapter of Holekh al ha-ruah. With their blessing, a new team of translators and editors embarks on a new journey to give this “text of exclamation points and question marks” yet another afterlife as a stand-alone piece titled “The Journey Without.”***

As Walter Benjamin delineates in “The Task of the Translator,” a work of linguistic art enters a new stage of existence with its translation into a new language, a new culture, and a new set of readers with different historical and cultural narratives. Through the act of translation it is reborn in a new form:

Just as the manifestations of life are intimately connected with the phenomenon of life without being of importance to it, a translation issues from the original—not so much from its life as from its afterlife.[8]The convoluted history of “The Journey Without” in its English reincarnation illustrates the independence of a text after it separates from its author’s pen. It is the second text by Natour to be translated into English.[9] As both writer and translator, Natour was painstakingly aware of the opposing prejudices of a Hebrew versus Arabic readership and did not see the act of translation as one dictated by fidelity to the original.[10] It required not only a reordering of letters but also a reconceptualizing of the delivery of an idea into a different culture. In the case of translation from Arabic to Hebrew, it was also a negotiation between two kindred cultures with conflicting narratives.

“The kinship of languages manifests itself in translations,” Benjamin writes. All suprahistorical kinship between languages consists in this: in every one of them as

a whole, one and the same thing is meant. Yet this one thing is achievable not by any single language but only by the totality of their intentions supplementing one another: the pure language.[11]Arriving at pure language via an expression of Natour’s words in English presented difficulties in its own right: conveying a local experience to an outsider readership. Shoshana London Sappir used the Arabic original as a primary source, while Mendel’s Hebrew translation served as a blueprint. In that sense “The Journey Without” symbolizes the kinship of languages as a child born to Arabic and Hebrew parents.

In “The Journey Without” this is all we present to the international readership of JLS: an afterlife of several creations from Natour’s expansive oeuvre.Nathalie Alyon

Notes

1 Salman Natour, Holekh al ha-ruah [Walking on winds], trans. Yonatan Mendel (Jerusalem: New World Press, 2017), 9. All translations into English are my own.

2 Ibid., 10.

3 “Hotze Yisrael” with Kobi Meidan, interview with Kobi Meidan, published December 2, 2014, accessed September 11, 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ssohNWXJXGk&t=306s.

4 Yonatan Mendel, “Aharit davar” [Epilogue], in Holekh al ha-ruah, 245.

5 Natour, Holekh al ha-ruah, 10.

6 Interview with Yonatan Mendel, August 28, 2017, Tel Aviv, Israel.

7 Mendel, “Aharit davar,” 245.

8 Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator,” in Selected Writings, Vol. 1, 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996), 254.

9 See Salman Natour, “The Chronicle of the Wrinkled-Face Sheikh,” trans. Yehouda Shenhav-Shaharabani, Granta 129: Fate, The Online Edition, Fiction, November 20, 2014, accessed September11, 2017, https://granta.com/The-Chronicle-of-the-Wrinkled-Face-Sheikh

10 In “Hashpaat ha-kore be-girsaot Holkhim al ha-ruah me-et Salman Natour,” Hamizrah Hehadash 35

(1992–93), Matityahu Peled describes how a Hebrew versus an Arabic readership influences Natour’s decisions as both author and translator of his own novel.

11 Benjamin, “The Task,” 256–257.

The Journey Without

Salman Natour

(Translated by Shoshana London Sappir)

The Glass Doors

She called from Paris to set up a time to meet.

She said: “All roads lead to Rome.”

So we agreed to meet in Rome.

I put down the receiver and laughed at our situation.

We’re meeting in Rome? Really? As easily as if we were meeting in Ramallah on Rukab Street or at Baladna ice cream, or on Khouri Street in Haifa, or in Tel Aviv, at a café on Sheinkin Street or Bograshov, or the Writers’ Guild cafeteria on Kaplan?

Yes, I told myself. We’re meeting in Rome, Fadwa and I, to talk.

After all, we are in the business of words.

We’ll meet to talk.

And write poems and dream about a boy who left his childhood behind him to become a hero.

We’ll meet to stop for a moment, to think and to plan the next stage in the campaign to liberate humanity.

But before we meet, I’ll have to make the journey out of here.

After all, I can’t travel to see you until I get past the checkpoints.

And until I show my identity card to a policeman who will grumble when he reads my name and lose his composure.

I won’t even get past the first checkpoint if I don’t prepare for it carefully.

I’m at home, packing and getting ready to go.

I take out anything that could arouse the suspicion of the policeman at the checkpoint or make the inspection officer at the airport nervous.

I carefully select the books I will take with me, making sure that I take my ticket and passport.

I forget that I already made sure, and make sure again, then make sure that I made sure that I’m sure.

I feel a lump in my throat on the way to the airport.

It happens when I get off the highway at the Ben-Gurion exit, on the ramp winding toward the airport. The airport extends over the land of the good village of al-Khayriyya, which was wiped off the face of the earth.

For those who know its history, the name evokes the ache of a lost world. For most Israelis, it is nothing but the name of a garbage dump.

Here I am, at the checkpoint. On either side stand a policeman, two soldiers, and numerous border guards with green berets. It is the first sign that I am about to embark on the adventure of departure.

I stop at the red light, and an armed border policeman approaches me. As soon as he reads the name on my identity card and passport, his face darkens.

The questioning begins: “Where do you come from and where are you going? Why? How? Where are your bags?”

One of the men with the green berets carries out his orders meticulously, ascertaining whether I am an Arab and whether I am a threat to anyone’s safety or state security or am carrying any secrets or love letters. He also has to make sure I don’t get on the plane until my nerves are completely frayed.

I breathe a sigh of relief after I get out of the grip of the border police. I drive toward the terminal. I see an airplane circling the sky for landing, while another floats up and disappears with a roar.

The large building seems like the boundary between me and space, or between my homeland and the outside world.

My favorite things about the building are the automatic glass doors.

They don’t ask you who you are; they don’t care about your identity or nationality.

When you walk toward the doors, they open. When you go through them and walk away from them, they close. I start to play with the doors like a little kid. In and out I go, delighting in their opening and closing at my command. I love those doors. They are free of racism.

On I went.

At the next inspection point, a young woman came up to me and said she was sorry she had to ask me these questions again.

She was doing it for my safety and security, she said.

I said: “Before you ask me, here are the answers to all of your questions:

I packed by myself.

I locked my suitcase myself, and since then it has been with me the whole time.

Nobody opened it, and nobody gave me any object or package.

No, not even an object that might look innocent.

No, I have no weapons or anything that could look like a weapon.

I don’t have a nail file or scissors.”

I rattled through the answers to the laughter of the security official, who

added a question about the purpose of my visit.

I controlled myself and said:

“The purpose of my visit is a personal matter. It has nothing to do with my

safety or the safety of the other passengers.”

She repeated her question but did not force me to answer.

Then she said to me: “Have a good trip.”

I went on. Another young woman was waiting for me as if we had made a date.

She looked pretty and alert. I looked at her with suspicion.

“Shalom!” she said and took my passport from me.

More than ten passengers moved forward toward the inspection post, while a black man in his thirties, in a black suit and a necktie, was asked to step aside.

He waited quietly, his face tense and confused, his eyes angry.

The officer asked him for his passport and ordered him to put his suitcase on the inspection table.

She asked him questions and he answered.

Then she asked him to take his suitcase and follow her.

They disappeared.

A blonde woman, also in her thirties, was about to open her suitcase when the security official asked her to stand aside. She started questioning her in Israeli English, and the blonde woman answered in English with a French accent.

I tried to eavesdrop and picked up bits and pieces. I understood she volunteered in a movement for solidarity with the Palestinians. She told the security guard she was at a women’s peace conference in the Galilee “for Israeli-Palestinian peace.”

Oh no, I thought. Here it comes.

That “Israeli-Palestinian peace” piqued the officer’s curiosity.

The officer kept asking, and the Frenchwoman answered at length. She spoke with incredible naïveté, as if she were speaking at a women’s demonstration during the intifada or a press conference.

Meanwhile, the beautiful girl who was waiting for me approached and asked for my passport and ticket. The girl was nice and very beautiful. It occurred to me to ask her why she didn’t work as a stewardess instead of a security officer, but I changed my mind.

She asked me to open my suitcase. I did.

She asked me where I was going. I answered.

She asked whether I packed myself. Yes.

Did anybody give me anything to deliver? No.

It seemed like everything was going well.

When she asked her questions and rummaged through my bags, I felt almost calm. I convinced myself she was only doing her job to keep me and the public safe.

Then she asked me to wait for a minute. I waited.

I started worrying everything was going wrong. My heart began to pound, and the minute lasted ten minutes and the ten minutes lasted a long time, full of insults and humiliations.

The Frenchwoman disappeared; an open suitcase was placed on another table. A Palestinian woman who looked like she was in her sixties stood in front of it.

An officer asked her in broken militarized Arabic: “Where going to?”

The woman asked: “What does ‘where going to’ mean?”

I intervened and shifted to real Arabic: “She means, ‘where are you going, ma’am?’”

I wanted to stay with the woman and translate for her, but the pretty officer said: “Your plane is taking off in five minutes,” and accompanied me to the ramp.

This is our homeland, my dear Fadwa, and every time we leave they make sure to remind us who the masters of this country are. And every time we return, they remind us again, before letting us go through those automatic doors.

Don’t condemn me, my dear, for this idle chatter, but the plane is taking off. I’m listening at full attention to the captain’s instructions, for my own safety, of course.

A Dream in Rome

I found the meeting place with Fadwa Habib easily. A little seafood restaurant overlooking the Colosseum. Before eating our seafood meal and drinking the local

wine, we talked. We talked about Scythopolis, the city of Dionysus, the god of wine.

Every once in a while the restaurant owner approached us. He was an elegant Italian with a big smile on his face, his thick mustache shaking with his easy laugh.

He showed a friendly interest in us. With a light step and a smile he went and brought a guitar and played us pleasant tunes. He sang about love, and we sang our

songs with him. He sang “Avanti Popolo,” and when he got to the chorus, “bandiera rossa,” we sang along:

Avanti o popolo, alla riscossa

Bandiera rossa, bandiera rossa

Avanti o popolo, alla riscossa

Bandiera rossa trionferà.

Forward people, to the rescue

Red flag, red flag

Forward people, to the rescue

Red flag will triumph.

We clapped and joined him again for the refrain:

Bandiera rossa la trionferà

Evviva il socialismo e la libertà!

So we sang, Fadwa Habib and I, a painter and a 57-year-old poet.

When I spoke, she listened attentively, whereas when she spoke, I constantly interrupted her until I noticed my rudeness. The Italian restaurant played in the

background.

It annoyed her that I didn’t know how to start talking about Scythopolis, the small city that is more than 6,000 years old. The city our ancestors called Bisan,

and then came others and called it Beit Shean. I thought to myself: O Scythopolis, I know the remains of the coliseum and its shattered arches well, and I even know Nysa, Dionysus’s wet nurse. And everybody knows Dionysus, the god of wine.

Fadwa cut off my thoughts and started telling her story:

“I was 16. I remember everything. You don’t remember anything, and you don’t know what happened that year, before you were born.

“But I was born there, and I don’t know who is living in my house today. Maybe the Jewish rabbi whom you told me you saw once with the chickens in my yard?

“I don’t really know how I feel about him anymore. Maybe it doesn’t hurt me as much anymore that a stranger is living in my house. Sometimes I think the house has already extracted from me all the pain it can bear.

“I’ve cried over my house a lot, but what use is crying?

“Sometimes it seems to me as if the house continues to hurt us only to make us let go of it. It’s tired of me bringing its memory back. It’s very painful to bring back the memory of a place. But it’s the only way to prove your loyalty to it.

“Yes, precious house, I am going to continue inflicting pain on you. I am going to talk and talk.

“Please do not interrupt me.

“It was the middle of the night. A group of soldiers arrived. They told us the planes were going to bomb us at dawn and that we had better leave town. They brought trucks. They loaded us on them. They dumped us near the bridge between Nazareth and Afula.

“They dumped us near the bridge, but the bridge was not there anymore. They destroyed it themselves to block our way back. We walked at night to Nazareth.

“My brother ran away and joined the fighters in Jordan. We slipped into Jenin. That is where our road of pain began—

“to Jordan

“to Syria

“to Lebanon

“to Cyprus

“to Paris

“to Rome

“to Tunis.

“Morocco was our last stop.

“I remember you told me that those immigrants who live in our house now are afraid. Are they really afraid? Tell me, the people who live in my house, did they actually say fear? Do they know what fear means? Did they tell you about their fear themselves?”

Fadwa stopped talking and waited for answers to her difficult questions about Jewish fear and Palestinian fear, about my fear and her fear, and fearful and terrified nations.

We started discussing our situation and tragedies, and wondered: Which fear is more legitimate—the fear of the victim or the fear of the executioner?

The deeper into the discussion we got, the more absurd our conversation appeared, sometimes ridiculous, and finally we summed it up absurdly.

We agreed we should probably be institutionalized in a mental asylum to treat our madness and release us from our complexes.

She ended our discussion and said firmly: “Don’t turn politics into psychology; don’t be naive. Ultimately, you must remember who is the wolf and who is the sheep in this story. You must not treat them as equals and compare the murderer and the victim.”

We said goodbye, and Fadwa left without telling me where she was going.

Chatting in Paris

Paris?

Paris is not my exile. I don’t pop over to the city of lights and cafés for a few days of leisure. But when Fadwa invited me to come see her exhibit, I came. Fadwa didn’t exhibit her work at a museum or art gallery but, rather, in the street and in an abandoned house, on the wall of a restaurant, and at a café.

That’s Fadwa.

I got to Paris in the morning. I don’t like being a tourist. I prefer just wandering through the streets.

My Parisian friend understood me and agreed to meet me in a café on Montparnasse Square on the Left Bank, which he described as a meeting place for Parisian writers and intellectuals. We agreed to meet at 9 a.m.

I was there at 8:30, drinking an espresso and eating a croissant. He didn’t show up.

The hands of my watch showed nine, and he still hadn’t come. When he arrived an hour later, I looked at my watch, and he looked at my watch too. He laughed because I hadn’t reset my watch.

Middle Eastern time, two hours ahead of Greenwich, and one hour ahead of France, wasn’t the only thing I brought with me to Paris. I brought a lot of other things from my Middle Eastern background as well.

During the hour I was waiting, I felt as if I were carrying my entire homeland on my back. I carried my village from Mt. Carmel, putting it on the table in front of me, next to the glass ashtray, which the waitress never let fill up with cigarette butts.

This is Paris café life in the blistering summer on the banks of Saint Germain and Saint Michel. Hundreds of thousands of Parisians fill every corner and every seat and chair in the cafés, looking at you as if you were a Middle Eastern idiot walking in the wide boulevards. Meanwhile you look down on them because they’re doing nothing but drinking their coffee, chatting, and staring at you.

At the beginning I thought that wandering around is an Oriental phenomenon, until I realized that my wandering actually made me a local. A big weight lifted off my shoulders as I told my disturbed self: When in Paris, act like a Parisian. I relaxed.

My friend took me to the café where Jean-Paul Sartre used to sit. This is where he sat thinking about existentialism and nihilism and what is and what it is all about, and I felt it could be a good place for contemplation. I started to go there every morning, sitting on a chair waiting for the waitress.

Bonjour!

Bonjour, Madame!

She brought me my espresso and croissant.

I got used to the same seat, or maybe it got used to me, and the only time I got upset was the time I got up and went to buy an Arabic newspaper from a kiosk across the street—when I came back, two elderly women were sitting at my table, and one of them had occupied my seat.

The waitress did not tell them it was reserved for that Middle Eastern man who smokes a lot, doesn’t do anything except watch passersby, and doesn’t speak French.

I got myself a different seat, waiting for my original seat to be vacated. As soon as the white-haired elderly ladies got up, I took my newspaper and cigarettes,

returning to my seat.

I returned as if I were returning from exile to my homeland. That is when I realized that a homeland is not a place, nor is exile. Both are depths where

the self meets the outside world.

I hid my bitter smile when I discovered my village, my homeland, and my birthplace in a Paris café, of all places.

I discovered how much my attention was diverted from them when I was there. I realized you are never in the place you love until you travel far away from it. It was there, in Paris, that I returned to my grandfather, the children of my neighborhood, to the old house, and to Haifa—to the cafés of Wadi Nisnas, where people sat and watched the passersby, thinking you were stupid if you hurried to work every morning.

I thought those Haifa people were stupid because they didn’t do anything except for talk, sip coffee, get mad at the backgammon dice for not doing what they wanted, and curse the world and the government.

I smiled.

Here is my beautiful Haifa in the heart of Paris. At home, Haifa loses another bit of itself every day, another bit of its memory, another word from its language, another shade of its scent. But for some reason, in Paris its memory comes back.

I listened to the French people’s chatter. I don’t know who the Parisians chatting in the cafés were cursing. I don’t know French, so I couldn’t tell who they were cursing. But I was sure they were cursing somebody. It seemed to me that every café has a government that its patrons curse, otherwise what’s the point of sitting there for hours drinking coffee?

I asked myself: Could the uprising of the oppressed erupt in the cafés and not in the offices or factories or mass demonstrations? Or perhaps it is the uprising of the middle class that will erupt there?

It didn’t comfort me that I belong to a generation that was born torn away from childhood dreams and idle chatter, a generation denied the right to just sit there and think about nothing, and that never had the time to idle.

Dear Fadwa,

The gravity of life seized us just like an afternoon nap takes away your wakefulness in the middle of the day, and now we have to learn to treat it dead seriously with eyes wide open, because we have no space left for dreams or superfluous fears, not even for empty words.

We eventually became proficient in the art of bombastic rhetoric and even in our casual café chatter the only thing we talked about was freedom and the Palestinian people and “the Palestinian problem.”

We were driven like sheep to the battleground, and we didn’t have the ability to resist. We were gripped by the dreams of our mighty leaders. We were so preoccupied with their great thoughts that we belittled ourselves and our own thoughts and aspirations.

We looked for great victories and in vain tried to stand tall, to skip over the pages of history and change it.

We imagined man to be like clay in our hands that we could shape, that history could be written based on the last line of the last page we reached and marked with a transparent bookmark.

And what did we end up with?

Nostalgia . . .

And how would you like, my dear Fadwa, to meet again and again at my Paris café? My café! The café that is mine!

It’s amazing how exile can turn into home.

The café in Montparnasse became my café, and that is where I met my friends.

A few days later Fadwa said to me:

“Since we met in Rome I’ve had no peace. You brought Bisan back to me the way I left it. You brought it back to my imagination and my dreams, and I can’t stop thinking about it. Before, it lived only in my memory. But now it came back to life for me. I laugh with it; I cry with it.”

She stopped talking, her eyes welled up, she drew in a deep breath, sighed, pulled a notebook out of her purse, and started reading me a poem she had written about Bisan. And another one. Tears ran down her cheeks.

Then she grasped my arm and dragged me to a Lebanese restaurant in the middle of Paris. It’s her place in Paris. That is where she sits when she visits the city and where she displays her work.

We stood in front of her pictures hanging on the restaurant walls. I was surprised to see she called one of them “The Road to Ein Harod,” after a novel by the Israeli author Amos Kenan. She told me she liked the book, which I had given her, because the road to Ein Harod also leads to Bisan, Beit Shean, and because it is about the end of the regime of Israeli generals.

She said when she read it she was overcome by terror, and she channeled her feelings into a large painting, two by two-and-a-half meters, on canvas taken from a refugee tent. With the imprint of the UN refugee agency still visible in its lower right corner, the painting portrayed a general carrying a cannon with two shattered corpses on it, a woman in the arms of a man in his fifties, and a lot of barbed wire. In the background bare mountains were swallowed by the sandy, gloomy horizon.

She wept, wiped her tears with her pink handkerchief, and said:

“I may never go back to Bisan in my life. Everything has changed. History, the reality, and the landscape. Bisan might wait for me until infinity, but to no avail.

I will not live into eternity, like the place.

“All I can do to show my faithfulness to Bisan is to leave my work and my poems and my testament. It will tell others:

‘Don’t forget your home!

‘Don’t forget the way home, the road paved with the black stones.

‘Don’t forget Bisan!’

“Maybe I’m fooling myself when I say that I despise life in Paris, Rabat, and Rome. Everything here is so beautiful. And maybe I’m lying when I say that I can’t stand traveling with a refugee card, even though it gets me a lot of sympathy.

“Yet, reality is what it is. I cannot change illusion into reality. And I can’t change reality into illusion.

“Remember, fear is fear.

“Do you know people who live their whole lives in a no-man’s-land?

“Do you know people who live their whole lives between fear and faith, between freedom and prison, between hope and despair, between poverty and wealth, between sadness and joy, between heaven and earth, and between life and death?

“Do you know anyone else who lives their whole life as if they were a character in a puppet show, with somebody else pulling the strings behind a curtain?

“The immigrants living in Bisan are probably staying there. Maybe one day I could at least go back, and even if I don’t go back to my house, I could live in a nearby village looking out on Bisan.

“Maybe I will come visit the people you told me about, and they will welcome me into their homes. Excuse me. Our homes. Just like they welcomed you.

“Are they their homes or our homes?

“I’ll come visit them, and invite them to visit me. We’ll exchange views and visits. Isn’t that the humanity demanded of me?

“Is that the only way the world will recognize my existence?

“Is that the only way it will remove the label of terrorist from me?

“Do I have to give up my memory to deserve to live? Will I only have a right to my place when I betray it?”

I spent two weeks in Paris. I wasn’t attracted to its museums or its great monuments, not because I didn’t have a tourist mentality but because I was a dumb Middle Easterner carrying his Metro ticket in his pocket, constantly listening out for other Middle Easterners speaking Arabic—another fool from the Orient whose heart also longed for the distant past, our legends, and even our wounds.

At that moment in Paris, I realized that you don’t love the time you live in. You must move away from it to love it. I also learned that when you talk about the past with great love, it means that your present is very bad.

The weather in Paris was very hot, because of all the car fumes; I couldn’t breathe deeply. I couldn’t fill my lungs with clean air the way I was accustomed to in my childhood on Mt. Carmel. My beloved Mt. Carmel, on one of whose peaks stands my house, my childhood.

I had nothing in this world back then except for the humid breeze from the sea. As a child I was satisfied with what nature gave me, and I dreamed of no other place. When life became oppressive, I would go down to the Valley of Palms. There I would jump from stone to stone and cut my way through the Aspalathus bushes, their thorns in my flesh causing me a sweet pain whose memory still gives me goosebumps.

Our village doctor once told me: “Mt. Carmel is the best pharmacy in the world, because every one of its plants is a medicine. The Aspalathus is aspirin, easing the very pain of living. Inula viscosa is good for the headaches you get from the morning news, and chicory is good for chasing away the terror of the evening news.”

Paris brought me back to the summer in our village on Mt. Carmel. I don’t know why the aroma of those distant summer days was brought back to me by the smell of the Paris car fumes, of all things.

It pleased me to know that our village smelled much better. The fragrance of the cow dung or the smell of the sheep who went through our yard every morning, how much lovelier they were than the Paris car fumes.

For a moment of silliness, the Citroens and Peugeots chugging through the streets of Paris, stopping, going, and emitting smoke, turned into cows rushing through the village alleys, raising dust in their wake as they spread out between the houses to unload their pure milk. Then they disappeared as they were forcefully taken to have their necks slashed by the butcher, so they could return to us in pieces.

What a terrible fate not to let a cow have the right to live her life in its fullness. Cows in our village did not experience old age, did not get to meet their grandchildren. Is that the fate that was decreed upon animals? Do cows have memories? Do they miss the place of their birth, too?

Do they have homelands?

In a teeming café on Boulevard Saint-Germain, I returned to the smell of coffee in my grandfather and grandmother’s home, to their faces and

voices. I sat there looking at the café goers like an idiot, with my suspicious Middle Eastern appearance, and went back in my thoughts to the hakawati, the old

storyteller of our town on Mt. Carmel.

He told tales of the ferocious heroes, Antara Ibn Shaddad and Abu Zayd al-Hilali, riding their horses to glorious battle. When he told his stories, we all gathered around him, leaning in to be first to hear the results of a duel over the heart of a beautiful girl in the desert, or about the heroism of the Arabs.

I said to my Paris friend: “Your city brought me back to my village. My little village.

I feel as if I were in it. My body is here and my heart is there.”

My friend gave out a full belly laugh: “What you find in Paris you will not find anywhere else in the world. Let alone in a village too small to appear on the map.”

I boasted to my friend, only half kidding: “You can find everything in our village.”

I felt I was in a duel, that I had to win. “Do they have za‘atar and ‘akoob in Paris?”

He shook his head no. The French flora did not include these two, that was for sure.

I felt as if I’d defeated him with a knockout.

They don’t, do they?

Meanwhile, we’ve made za‘atar into an effective weapon against imperialism. They drop bombs on us and we spray them with za‘atar.

Zaʿatar in London

Let’s not beat about the bush.

Our troubles did not begin in Paris or in Rome.

I might as well go straight to the home and castle of the ring leader.

I made up my mind to go by myself, carrying with me the memories of my grandfather and my father. I came back to you, London. Which, as the Arabs used to cry in their revolt against the British in Palestine, is the stable of our horses!

London, the city where the conspiracy was designed in all of its details.

The city to which I am taken again and again by the stories of my grandfather, my father, and the wrinkled-face sheikh who told me, with sparks flying out of his eyes: “By God, if I could, I would blow it up until doomsday.”

To this day it’s hard for me to comprehend the animosity that generation harbors for Great Britain. It seems to be a hereditary hatred with very strange rules, because I have yet to meet an old sheikh who didn’t curse and badmouth Britain with all he had, while, in the same breath, had he been given one last wish, he would have wished to visit London.

Each one of them has etched in his memory an unflinching image of a British policeman. No matter whom you talk to, they will describe a man in his thirties wearing a beret, shorts, and a buttoned, brown uniform shirt with short sleeves. He will be holding a whip, never smiling, and saying only two words: “Hands up.”

All I could think about on the way to that accursed city was revenge. At that moment, I felt I was settling an old account with London and with Capt. Schiffer, who ruled our town for thirty years and left it bleeding.

Those feelings only stopped when I reached the border terminal between France and England. There were two lines in passport control: one for EU citizens, who could go through it with little control, and another one for non-EU citizens, including me.

They took my passport and a policewoman asked me to wait, so I waited.

A blond British officer asked me to open my bags, and as soon as I unzipped them and he saw the bag of zaʿatar, he lost his composure. I realized the curse of the zaʿatar had followed me all the way to England.

The officer pulled the bag out nervously and asked three other officials to join him. They ordered me to stand aside. A large dog came and started sniffing the suitcase, my body, and the zaʿatar, and I couldn’t help but burst out laughing. I said to myself: Here it is again, the curse of the zaʿatar.

I asked the officer in English: “This is zaʿatar. Do you know what zaʿatar is?”

The blond officer looked at me helplessly. He had no idea. Had he been the son of the Englishman who ruled our town on Mt. Carmel, home of the zaʿatar, he surely would have taken a deep breath of its good smell. But that was not the case.

Within minutes I was surrounded by three other officers who asked me to stand by the wall, so I did.

“Hands up!” they said.

I raised them.

The dog started sniffing me enthusiastically.

London declared a state of emergency. The British Army went on high alert. Her Majesty’s Navy started moving ships out of the port. The Royal Air Force

readied its planes for emergency takeoff. The reserves were called up.

And what caused all this panic?

A little bag of zaʿatar.

They took the bag, ordered me to sit on a wooden chair, and the officer started investigating me.

“Where did you come from?”

“Where are you going?”

“Is anybody expecting you in London?”

“Why are you carrying that bag?”

I said: “If push comes to shove in London and I have nothing to eat, I’ll always have my zaʿatar. Do you know what zaʿatar is?”

They didn’t answer and left me sitting alone.

While I was waiting, I wondered: How did they manage to rule our country for thirty years if they can’t tell the difference between ground zaʿatar and gunpowder?

Or maybe it was all deliberate? Maybe they’re afraid of zaʿatar because they know it strengthens the memory, and they want to erase that memory for eternity?

I was pleased that my little bag of zaʿatar managed to defeat the entire United Kingdom this time.

That is the secret of zaʿatar.

It begins with a curse and ends with a blessing.

The curse of the zaʿatar brought me back to the story of Abu Salah al-Lawah, the old sheikh from our town who refuses to die and still has his memory and his stories, and still wraps his headdress around his waist when he leads the dabke dancers.

He said: “One day my wife, Umm Salah, asked me to take her to pick zaʿatar. We rode our donkey into the hills. We picked some zaʿatar. We tied it to the donkey and rode back. On the way home a green jeep from the nature protection agency stopped us. One of the inspectors got off.

“He shouted at us in Hebrew: ‘Stop! Stop! Stop!’

“We hit the donkey’s brakes and stopped.

“The son of a bitch started screaming at us:

“‘No zaʿatar! No maramiya! Noʿillet! No khubeze!’—which means: no thyme, no sage, no hyssop and no mallows.

“‘But, Sir,’ I said, ‘this one is good for your stomach and that one for your nerves and the other one for a headache. What’s the problem? We’re just taking a little home.’

“‘Nope,’ he said in that broken Arabic again. ‘You’re “destructing” nature.’

“‘I’m “destructing” nature?’ I asked.

“He didn’t reply. He just confiscated all the sheaves we had picked and even wrote me a ticket. Two months later they hauled me into court, charged me with ‘destructing nature,’ and fined me 2,000 shekels.

“A year later I open the newspaper and what do I see but a picture of that nature guy spread across half of the page. The son of a bitch opened a factory for zaʿatar and sage. In the advertisement, under his smiling face, it said: ‘This one is good for your stomach and that one is good for your nerves and the other one is good for a headache.’

“And I’m the one who ‘destructed’ nature. Huh.”

How I wished I had Abu Salah with me to help me confront the British Empire.

Half an hour later a young man came holding the bag and laughing wholeheartedly.

He said to me in Arabic: “What blithering fools.”

I learned from the young man that he was a Palestinian working as a driver in the area, and he was called in as an expert on the matter of Arab plants.

He asked me: “Do you know anybody in London?”

I said: “Yes, I have friends I’m going to visit.”

He said: “Take this number of my friend Marwan. He’s an exile, from the Tulkarm refugee camp. He’ll help you manage in London.”

I said: “Brother, please take this bag and keep it. The only reason I brought it with me is so that I could give it to any Palestinian I met who had not smelled the smell of the homeland for a long time. Since the beginning of my journey, I’ve been taking it wherever I go and the only times it’s been opened have been for investigations. So, how would you feel if I gave you this bag, with the smell of the homeland, as a gift from one brother to another?”

His eyes moistened and he took a deep breath of the smell of the zaʿatar.

We embraced as brothers. I left, took the bus from the terminal to Victoria Station, and called Marwan. Within ten minutes a young man in his twenties was standing before me. He was pulsing with vitality, with a big smile on his face.

He said: “I will not let you stay in a hotel. I am going to give you an apartment to stay in.”

I learned from him that he owned five small apartments in London that he rented to students, only from the Third World and for low rent, out of solidarity of the

Palestinian people with the nations of those countries, living under oppression and poverty.

Marwan was nothing like I expected from Palestinians living in exile, just like London’s traffic confused all of the driving rules I knew.

Said Marwan: “I’m going to get back at them. They colonized our country for thirty years only to hand it to the Jews. So I’m going to buy all of London. I’m getting rich here so I can buy it with their money.”

We laughed a lot. We laughed at ourselves and our sweet revenge.

I said to him: “Marwan, you and I are not much different from our fathers. Listen to this story.

“There was a British officer in our town. Every time he felt like taking revenge, he went and ordered people to leave their homes and gather in the town square, just like that, for no reason. He made them stay there for an hour or two until he ordered them back to their homes.

“Abu Salah decided to take revenge on him.

“He waited for the officer to order the villagers to the town square, and when he did, Abu Salah climbed onto the roof.

“The officer shouted to him:

‘Come on! Come on here!’

“Abu Salah shouted back at the officer: ‘Come on inta,’ which means: ‘You “come on” yourself.’ I’m paralyzed and cannot move. I can’t climb down. If I try, I’ll fall down and break my neck.’

“The officer approached him and stood against the wall and said: ‘Come, I’ll help you down.’

“Abu Salah let down his legs and threw them over the officer’s shoulders. The officer started walking.

“Abu Salah started shouting in Arabic at the top of his lungs: ‘Hey townspeople: By God, we ride them. We ride them like donkeys. We ride Great Britain.’

“People started clapping and shouting. Even the officer was happy. After all, he didn’t understand a word of Arabic. At first he thought they were congratulating him for his generosity.

“Later, when he found out what was really going on, he got a hold of Abu Salah and taught him on his skin what the power of Great Britain really means.”

I said to Marwan: “How long can we keep carrying our anger and rummaging through the past?”

He said: “Until we restore our lost honor. Until the end of days.”

Marwan is a good chap to the point of innocence. Even when he talked about revenge and vengeance, he sounded like an innocent child who had his toys stolen.

His revenge is sweet as honey, I thought. He is not after death or destruction or damage.

As soon as I started looking for coffee shops in London, I realized right away that it is a cursed city that knows no quiet. It is a city of fog and commotion. Its streets are crowded with people from different places and nationalities, Westerners in suits or dresses mingling with Arabs in headdresses and robes on their way in and out of its stores.

All I could think of were the verses that used to comfort our grandparents during the Arab Revolt:

“Balfour, khaber dawlatak

London, marbat kheilna.”

“Balfour, tell your government,

London will be our horse stable.”

I asked Marwan: “Where do these people in headdresses tie their horses?”

“At Heathrow airport,” said Marwan.

“We exchanged our Arab horses for Boeing 707s. There they are, tied at the airport stables.”

Marwan introduced me to a Palestinian friend who was born in Nablus and grew up in Amman. He went to school in Amman, then went on to study business management and trade in London, where he now runs the family business.

He said to me: “You’re from Daliat al-Carmel, right?”

I said yes.

He said: “Would you like to see, here in London, a picture of your village from sixty years ago?”

I said: “Of course, I’m sure I’m going to be amazed.”

I felt a chill run down my spine when he pulled an old picture out of his briefcase showing three old men sitting on a stone bench with Middle Eastern coffee cups

and a brass pitcher laid out in front of them. Each of them held a string of prayer beads in his hands. They looked at the photographer as if wondering: “What does the stranger want?”

I tried to figure out who the three old men from my town were, but I didn’t manage to. But I could tell they were sitting in the yard of the western neighborhood.

On the photograph it said in English: “Daliat al-Carmel. Three old men. They do nothing.”

I asked my Palestinian friend: “Where did you get this picture?”

“I bought it here. On Sundays, there’s an antiques market where you can find memorabilia, stamps, old pictures, all kinds of things that were found in the homes of old English people who died, and their grandchildren put up for sale. Probably some English tourist visited your village and took the picture.”

That’s how the old objects found their way from the warm houses to the street corners.

I said: “That’s strange. Why did that Englishman decide to take a picture of three old men doing nothing? And what about you? Why did you choose that out of all of the antiques you found on the street?”

He said: “Because I long to have contact with that generation. Whether I’m here in London or in Amman. It was the same when I was in Nablus, and before that in al-Khayriyya, where my father and mother come from. My father always talked about the village, and I always felt as if I lived there with them.

“I have pictures in my mind that I never saw, of its houses and streets and schools, vivid pictures that never leave me. I know the color of the school windows, I know where the basil grew along the staircase next to my father’s classroom, and I know they used to crush its leaves every time they went into the classroom, to spread its scent.”

He stopped to take a deep breath.

I asked my Palestinian friend: “Do you know what became of al-Khayriyya?”

“I do,” he said. “I know full well. But could you tell me, is anything left of it? I bet on your way here you went through our land and when you took off you circled its sky. Did you see a stone house with a luscious jujube tree in its garden?”

We were crossing a bridge over the Thames when he asked me, and I wondered to myself: How do you begin the story between the homeland and those who are

outside the homeland? Or, between the place you are and the place that has left you?

That is our situation, my dear Fadwa. We have become nothing but a bundle of worries, and we are not Arabs unless we are in exile.

I am an Arab, therefore I am an exile.

Arab places have nothing to pull you back to them, only things to keep you away from them.

The enemies of yesterday are still the enemies of today.

But what about the friends of yesterday? Today we have no friends left.

Once upon a time we used to sing about our freedom and liberation, but today we just cry about our situation. When you meet your past you cry about your present, barren as the desert soil.

Our present has become a desert that expels you every time you try to get close to it. But the present that became a desert always brings you back to the beginning of the story, to the airport

that occupies

the good land

of al-Khayriyya.

Literary editor: Michael Dickel

The four segments are taken from Safar ʿala safar (Journey over journey), a trilogy of Salman Natour’s novels, which was published in Hebrew under the title Holekh al ha-ruah in February 2017 (translator: Yonatan Mendel) as the first book of Maktoob. The Maktoob book series, the flagship project of the Translators’ Circle at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, is devoted to the translation of Arabic literature into Hebrew. The project is supported by Van Leer and Mifal Hapais and is published by Olam Hadash.

Leave a Reply