Analysis by Idan Barir: “I Own Nothing Save My Dreams”: Ezidis Recount Their Tragedy

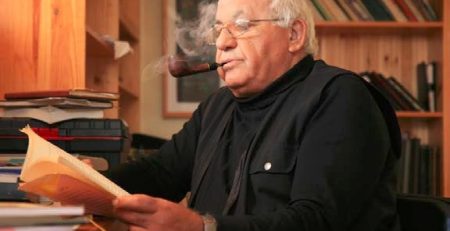

Idan Barir

August 2014 was probably the most difficult and blood-soaked month in the recent history of the Ezidi community in Northern Iraq. The Ezidis are an ancient Kurdish-speaking ethno-religious group, whose believers are considered by Islamists to be “devil worshippers” and thus “the worst of infidels.” On August 3, 2014, Islamic State (IS) militants invaded the Shingal (Kurdish for Sinjar) region—an area that was populated at that time largely by Ezidis—with a clear and preannounced mission: to eliminate the Ezidi presence there. The Kurdish Peshmerga forces, the only military force that had pledged to grant the persecuted and threatened Ezidi minority protection, surprisingly withdrew from the battlefield in the entire Shingal region, leaving some 350,000 Ezidis at the mercy of their worst of enemies. Approximately 80,000 Ezidi men, women, children, and the elderly—who could not flee by car to Iraqi Kurdistan—had to find refuge among the peaks and ravines of Mount Shingal in the scorching heat of the Iraqi desert. Hundreds of Ezidis, mostly children, the sick, and the disabled, lost their lives to famine, thirst, and disease during the weeks spent on the mountain. Ultimately, the stranded Ezidis were rescued by Kurdish forces from Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan) and were transported through Syrian territory to Iraqi Kurdistan. On August 6, only three days after the Shingal atrocities took place, IS forces invaded the Ezidi villages of Baʿshiqa and Bahzani, some sixteen kilometers (ten miles) east of IS-controlled Mosul. They took advantage of both the Peshmerga’s retreat and the horror that befell the town’s residents after seeing what had happened in Shingal, quickly occupying the towns and driving their entire Ezidi population, estimated at 30,000, into Iraqi Kurdistan.[i]

The horrific events of the Ezidi genocide (ferman in the Ezidi discourse) in Shingal left the Ezidi community battered and bruised, with its communal backbone completely shattered. At present most of the Ezidis are exiled in their own country, living in refugee camps and on construction sites in the cities and towns of Iraqi Kurdistan. Many of them are deprived of the basic needs of life, of a functioning school system for their children, of privacy, and of personal hygiene and health. Most of them are dependent on the kindness of foreign aid agencies and international humanitarian organizations for their basic needs. In addition to their unbearable present, Ezidis have to face the physical, mental, and moral consequences of their past, as many of them witnessed their houses, lands, and property destroyed and looted by IS militants, and they suffered the loss of relatives during the escape to the mountain. Another issue that continues to haunt the entire Ezidi community since August 2014, one that casts a giant shadow on the community’s ability to return to normal life, is the thousands of Ezidi women and girls who were captured in Shingal by IS militants and enslaved for sexual and domestic purposes. The trauma from the events of last year grew even deeper as a result of the bitter feelings of betrayal and abandonment experienced by Ezidis toward both their Muslim neighbors, who assisted the IS militants in their deadly campaign, and the Kurdish authorities, who fled the scene and failed to fulfill their only commitment to them. The uncertain future of the community and the absence of a solution that would ensure its survival might turn the trauma of last year’s events into a death blow that will bring a sad end to this ancient community.

These issues regarding the past, present, and future comprise the core concerns of the Ezidi community these days, in what seems to be the most difficult period in its history. Since the ferman in Shingal, poetry has become one of the most fascinating outlets reflecting these concerns, allowing a creative space for the clarification and exchange of ideas, thoughts, fears, plans, and even hatred and contempt. The Ezidi poets presented here—Sarmad Saleem, Haiman Alkarsafy, Murad Suleiman Allo, Saado Bajoo, Saleh Mado, Haji Mershawi, and Sana Tapany—are young and old, women and men, experienced as well as green, and constitute a representative sample of modern-day Ezidi poets. All set out to write poetry as both a therapeutic tool and a means to express their opinions. Poetry allows them to take an active role in the Ezidi communal and political discourse of the post-ferman period and to comment on the situation of their community, their longing for their villages, communities, and friends, and their hopes and fears.

The vast majority of the Ezidi poetry published after the Shingal events, and all the poems in this selection, were written in Arabic. While the Ezidi community is predominantly a Kurmanji-speaking minority, Arabic has been the cultural and educational language of most Ezidis in all regions inhabited by the community. It is also the mother tongue of Ezidis from the towns of Baʿshiqa and Bahzani, represented in this selection by two poets (Mershawi and Tapany). Furthermore, Arabic is a richer and more standardized language than the Kurdish language, allowing the poets more flexibility and breadth of expression. Using Arabic also enables the poets to direct their words to their tormentors, as may be seen, for example, in Saleh Mado’s poem Don’t Curse My Mother. A combination of these reasons may explain why Ezidi poets choose to write in Arabic rather than their native Kurdish. That being said, writing in Arabic puts the Ezidi poets and writers in an astounding duality on a personal, political, and literary level. They draw from the writing tradition of Arabic poetry and gather various sources of influence from it. At the same time, however, they live in a constant state of fear of their Muslim Arabic-speaking neighbors, torchbearers of this old tradition, who often persecute them or support their persecutors. This duality is most evident in their writing and poems, making them even more interesting.

This new wave of Ezidi “posttraumatic poetry” provides an invaluable glimpse into the depths of the community’s traumatic collective memory—of events of the last year and of the long line of persecutions against them. These poems often fluctuate between the extreme poles of hope and despair, victimhood and might, pride and shame, collectivity and paranoia, allowing a rare and unusual perspective of the mindset and range of victims’ emotions, while the disaster is befalling them and immediately thereafter. The poems collected here deal with topics that have preoccupied the Ezidi discourse during the past year. First and foremost, they present Mount Shingal in its many facets: Shingal is a place of special holiness and historic importance for the Ezidis, as is highlighted in Saado Bajoo’s poem with the title “Mount Shingal.” For many Ezidis, Shingal is also home in the broadest meaning of the word: a geographical space that contains an elaborate Ezidi human mosaic and that serves as a lost childhood landscape that is now an object of longing. While already lost for good, Shingal is still perceived and experienced as home in the memories of its former residents, even in the memories of Ezidis from different regions. Poet Sarmad Saleem, a native of Shingal, reveals in the untitled poem translated in this selection the gaps in memory between the present reality in Shingal and the way it was experienced before the attacks.

The poems are rooted within the Ezidi historical consciousness, placing the Shingal atrocities of last year on a long historic continuum of persecution and attacks against them on religious grounds. It is therefore no surprise to find a line such as this, from the poem “The Captive,” written by the senior poet from Shingal, Murad Suleiman Allo: “We will restore the glory of Dawûd, Mirza, and Basha.” The three names mentioned are those of legendary Ezidi leaders from the Ottoman period, remembered and identified above all with the protection of Ezidi honor in the face of past fermanat (annihilation campaigns, or attempts at genocide). The connection made between these three leaders and modern-day Ezidi leaders who paid with their lives for the defense of Shingal, is equally natural and unsurprising. However, Ezidi honor is not confined merely to communal cohesiveness or to standing up against external attacks on the battlefield: it may also be a very personal honor, a concept of special importance in the traditional Ezidi community. This honor is perhaps best demonstrated in Saleh Mado’s poem “Do Not Curse My Mother.” Personal and family honor are portrayed as values to be protected with no less determination than the protection of human lives, even at the cost of expulsion and exile.

The Ezidi identity, both prior to and following last year’s events, is another recurring theme in these poems. In “Identity,” Haiman Alkarsafy details for us, the readers, the various components and features of this complex identity: “my Ezidi self, / my language, / my Shingali self—.” On the one hand, this identity is deeply rooted in Kurdistan. (As an Ezidi friend once told me, “For Ezidis the sky speaks Kurdish and the earth speaks Kurdish.”) On the other hand, it seeks to shake off the Kurdish identity, mainly after what many Ezidis see as the Kurdish betrayal of their people. The outcome is an emerging Ezidi identity, personal and communal alike, that is firmly anchored in the community’s traumatic collective memory more than anything else. Poet Haji Mershawi demonstrates this connection with past traumas and the commitment to “Ezidiness” in his poem “Ezidi I Am”: “I bear the pain of 74 genocides / and a million years of sobbing. /[ . . .] / Agony is inherent in my genes.”

The constant movement of the new Ezidi identity, between heroism and victimhood, strength and weakness, is another interesting theme emerging from these poems. This tension between two extremes, so distant from each other, stems from the discrepancy between the Ezidi self-image of a courageous and determined people unwilling to compromise their beliefs and the bitter Ezidi reality of misery and helplessness. This discrepancy can be shown in the difference between two poems in this selection. The first is Murad Suleiman Allo’s poem, stressing the greatness and bravery of the Ezidi. The second is the call for the rain to have mercy on the people of Shingal after their tragedy, which appears in Sana Tapany’s poem “Rain Rain.” These lines show the many faces of the Ezidi self, as imagined by Ezidi poets, and may be an account of the Ezidi mood and state of mind in their posttraumatic stage.

The task of translating these poems was not easy: translating poetry is difficult, more often than not compelling the translator to sacrifice many of the original poem’s characteristics, such as the rhyme, tone, meter, or enjambment, for the sake of a fine translation. In addition this highly personal poetry, written under impossible conditions by poets experiencing their darkest hours, was very difficult for me to fully grasp in the beginning. It took me many hours of reading and contemplation, as well as long hours of conversations with the poets themselves, to understand that the Ezidi poetry written after August 2014 is not typical of their poetry, and beyond its mere poetic value, it is a capsule of feelings and emotions as experienced by an entire community. For me the translation of this poetry is part of a broader commitment to the Ezidi community: I dedicated my MA thesis to the emergence of the new Ezidi identity and found many close friends and partners in the Ezidi communities in Iraq and Europe. After the outbreak of the Shingal atrocities, I felt it was time for me to reciprocate to a community that had helped me so much and that had been so generous to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to the many Ezidi poets, and specifically to all those presented here, who were so kind as to share their poems with me and who allowed me to be very intimately involved in their torments, fears, and hopes. I am also deeply indebted to Michael Dickel, who, with some magical waves of his editing wand and with his expertise and experience, polished the translations and taught me some important lessons in word choice and the music of language. Thanks to the effort and good will of these people, I believe that the present undertaking, part of a broader translation project involving poetry written by more than twenty Ezidi poets, will help amplify the voice of the oppressed and humiliated Ezidis.

I believe that in the future, when thorough research is conducted on the Shingal atrocities of summer 2014, this poetry will stand out as being among the few literary and textual products created by victims of atrocities at the time and place of the occurrences. This, above all other things, is what gives this poetry its importance and what makes its translation so necessary and interesting. That said, the long-term importance of the poetry does not in the least diminish its beauty and quality, which makes its translation not only an important and timely task but also a very pleasant and satisfying one.

Prior to approaching the poems themselves, some technical notes are required: although their poetry is written in Arabic, the terminology used by most Ezidi poets is in Kurdish. I chose to respect this choice, and throughout this preface the Kurdish terms were preferred over Arabic alternatives. Thus, Ezidi, the name most commonly used by Ezidis themselves for their community and religion, was used rather than the more familiar Yezidi or Yazidi; the Kurdish name Shingal was used instead of its Arabic form, Sinjar. Similarly, other idiosyncratic Ezidi religious and cultural terms are used throughout the translations, and where needed, clarifying footnotes were added.

[i] Mohammed A. Salih, “Kurds Prepare for Counteroffensive as US Strikes IS,” Al-Monitor, August 10, 2014, accessed September 3, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/08/kurds-iraq-isis-islamic-state-us-strikes-sinjar-yazidis.html.

Leave a Reply