Living with This Name: “Foreign” Names of Turkey’s Non-Muslim Natives

Rita Ender was born in Istanbul in 1984. She graduated from the Saint Joseph French High School in Istanbul in 2003 and from Marmara University Law School in 2008. She has worked as a lawyer since January 2010. She holds master’s degrees from Galatasaray University and Panthéon-Assas University (Paris II) and has worked in the field of minority rights.

Ender, who has written for a variety of newspapers and magazines since 2001, has published three books: Mümkündür Mucizeler [Miracles do happen] (Istanbul: Gözlem Publishing, 2007); Kolay Gelsin: Meslekler ve Mekânlar [May the work be easy: Professions and places] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2015), and İsmiyle Yaşamak [Living with this name] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2016).

She also produced and directed the documentary film, Las Ultimas Palavras, about Ladino, also known as Judeo-Spanish, a language on the verge of extinction in Turkey.

What’s in a Name?

Introducing Rita Ender

Introduction by Nathalie Alyon

My grandmother is the only one in our Turkish-Jewish family to bear a Muslim name. I remember asking about its origins many years ago, when I was about ten years old. At first she shrugged, saying that her mother simply liked the name. Yet when I inquired about its meaning, she couldn’t give a clear answer. I pressed on. It was the time of Hitler, she finally explained: “My parents wanted to protect me. They thought a Turkish name would be safer.

My grandmother may have confronted fewer questions in her day-to-day life as Belkis than she would have as an Esther or a Rozi. Nevertheless, a local name didn’t spare her from justifying why her name is what it is—only this time, she had to provide these explanations to her own granddaughter. Perhaps I remember this conversation so distinctly because I was already facing the challenges of my own “foreign” name, living and studying in Istanbul as “Nathalie,” which—along with Natasha— had become synonymous with “prostitute” after the influx of Russian women who arrived in Turkey after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Living with my name, I understood at an early age that names carry social and communal significance beyond linguistic preference.

The following essay by Rita Ender exposes the nuances of living with a foreign name in Turkey. It is based on the author’s book İsmiyle Yaşamak (Living with this name), which presents the author’s interviews with forty-five non-Muslim natives about one of our most basic possessions: our names. Like my grandmother, Ender’s elder interlocutors were born during a tumultuous time. In the decades before and after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, both the state and the people living in those lands were busy negotiating who was or could become a Turk. [1] This negotiation is hardly over—the conversations in Ender’s book demonstrate that the debate over who is “local” or “foreign,” and according to which criteria, is ongoing. Markers such as “majority” or “minority” can hardly be understood in plain terms even among Muslim communities in Turkey—a Sunni Kurd could be a member of a minority group for ethnic and linguistic reasons, while an Alevi Turk could be considered part of one for religious reasons.

In presenting names as another frontier in the nationalization project of multiethnic nation-states like Turkey, each interview in Ender’s compilation leaves the reader with more questions, as each individual presents a unique history, revealing further complexities beyond the ethnic or religious traditions that often influence our identities: What are the roles of names in sustaining a minority consciousness? Which markers, alongside names, are used to erode minorities’ rights to civil inattention? How do minorities negotiate pressures for assimilation and acculturation as their communities dwindle in size?

Ender’s straightforward style in presenting her interviewees’ viewpoints also serves as a much-needed bridge for a gap in the documentation of the oral history of Turkey’s minority communities. While scholars and independent researchers have made significant strides in this arena in recent decades, Turkey’s diverse communities are in dire need of having their experiences recorded. [2]

Ender’s conversations touch upon sensitive moments endured by minorities during Turkey’s early history, as well as more recent events such the murder of Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in 2007 and the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident. Certain traumas that have become watershed moments in collective memory surface in the interviews like invisible threads connecting these diverse communities. For example, some conversations mention the “Citizen, Speak Turkish!” campaign, which began in 1928 and continued throughout the 1930s, targeting both Muslim and non-Muslim minorities who faced a fierce program of Turkification under the auspices of nation building in the new Turkish republic. [3]

As an oral history project, Ender’s book also shines a light on the symbolic influence that these moments in Turkey’s early history had in shaping the communal and national consciousness of the country’s minorities. Among Ender’s Armenian interviewees, memory of the Armenian Genocide of 1915 evokes a powerful emotional response. Almost all of them mention the tragedy and how it influenced their families. Other traumas that come up include the 1936 attacks on the Jewish communities of Thrace, the 1942 Varlık Vergisi (“Wealth Tax” levied on non-Muslim citizens), and the 1955 pogroms against non-Muslims in Istanbul.

Another symbol of minority-majority relations at both state and communal levels is the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). This peace treaty delineated the borders of the republic and overrode the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), which the Turkish national movement had rejected as a catastrophic division among foreign powers of what was left of the Ottoman Empire. The Treaty of Sèvres left a scar on the Turkish collective memory that has proven difficult to heal. Arguably, the rights granted to non-Muslim minorities as part of the Lausanne treaty contribute to the so-called Sèvres Syndrome whereby conspiracy theories often accuse minority communities of involvement in foreign influence and invasion. Even the most basic assertions of identity among minorities are often interpreted as attacks on the territorial integrity of Turkey. [4]

The freedom to name is one of those basic rights that many feared to exercise. The president of the Kadıköy Greek Orthodox Community Churches, Schools and Cemetery Foundation, Yorgo Istefanopulos, explained to Ender during their interview that at times, minority communities chose to use Turkish names to hide their identities. “During the period when the ‘Citizen, Speak Turkish!’ campaigns were ongoing, everybody denied their names. For example, we knew a Mr. Fedon. He instructed us to never call him by Fedon. Only Feridun! So we called him Mr. Feridun. His wife’s name, Triandafilia, means “rose” in Greek, so she became Mrs. Gül. Her sister Thedolosula became Şule. They didn’t want to use their own names. They were truly afraid.” [5]

That a discussion about something as innocous as a personal name conjures such painful moments in history is telling. Yet it would be a disservice to these communities to focus solely on the traumatic. Rather, İsmiyle Yaşamak celebrates the diversity and individuality of our names and our identities. Starting each interview with a pleasant and deeply personal discussion about the origin and meaning of her subjects’ names, Ender narrates communal and family histories. For example, after recounting the story of his being named after a character in a movie that his mother admired, Nino Varon explained that “Nino means storm. ‘El Niño’ is the name of a storm in Spanish. . . . Coupled with my last name, Nino Varon is very phonetic. Like an Italian fashion label or a French lighter company. . . . And for Turks it’s hard to categorize. People wonder—is he Greek, French, Italian, Armenian? The last thing they think of is that I am Jewish.” [6]

Ender’s study poignantly reveals, through honest discussions about our names, the multiplicity of identities that make up a person, beyond those of ethnicity or religious tradition. They embody the diversity—be it of age, gender, profession, life experience, or worldview—within each individual, community, and country.

Notes

[1] See Soner Cagaptay, Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk? (London: Routledge, 2006).

[2] For an overview, see Leyla Neyzi, “Oral History and Memory Studies in Turkey,” in Turkey’s Engagement with Modernity: Conflict and Change in the Twentieth Century, ed. Celia Kerslake, Kerem Öktem, and Philip Robins (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

[3] Senem Aslan, “‘Citizen, Speak Turkish!’: A Nation in the Making,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 13, no. 2 (2007): 245–272.

[4] Baskın Oran, Tűrkiye’de Azınlıklar: Kavramlar, Teori, Lozan, İç Mevzuat, İçtihat, Uygulama [Minorities in Turkey: Concepts, theory, Lausanne, legislation, case-law, implementation] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2008), 161.

[5] Yorgo İstefanopulos in Rita Ender, İsmiyle Yaşamak [Living with this name] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2016), 281. All translations are my own.

[6] Nino Varon, in ibid., 215–216.

- + About the Author

-

Rita Ender was born in Istanbul in 1984. She graduated from the Saint Joseph French High School in Istanbul in 2003 and from Marmara University Law School in 2008. She has worked as a lawyer since January 2010. She holds master’s degrees from Galatasaray University and Panthéon-Assas University (Paris II) and has worked in the field of minority rights.

Ender, who has written for a variety of newspapers and magazines since 2001, has published three books: Mümkündür Mucizeler [Miracles do happen] (Istanbul: Gözlem Publishing, 2007); Kolay Gelsin: Meslekler ve Mekânlar [May the work be easy: Professions and places] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2015), and İsmiyle Yaşamak [Living with this name] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2016).

She also produced and directed the documentary film, Las Ultimas Palavras, about Ladino, also known as Judeo-Spanish, a language on the verge of extinction in Turkey.

- + Analysis

-

What’s in a Name?

Introducing Rita Ender

Introduction by Nathalie Alyon

My grandmother is the only one in our Turkish-Jewish family to bear a Muslim name. I remember asking about its origins many years ago, when I was about ten years old. At first she shrugged, saying that her mother simply liked the name. Yet when I inquired about its meaning, she couldn’t give a clear answer. I pressed on. It was the time of Hitler, she finally explained: “My parents wanted to protect me. They thought a Turkish name would be safer.

My grandmother may have confronted fewer questions in her day-to-day life as Belkis than she would have as an Esther or a Rozi. Nevertheless, a local name didn’t spare her from justifying why her name is what it is—only this time, she had to provide these explanations to her own granddaughter. Perhaps I remember this conversation so distinctly because I was already facing the challenges of my own “foreign” name, living and studying in Istanbul as “Nathalie,” which—along with Natasha— had become synonymous with “prostitute” after the influx of Russian women who arrived in Turkey after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Living with my name, I understood at an early age that names carry social and communal significance beyond linguistic preference.

The following essay by Rita Ender exposes the nuances of living with a foreign name in Turkey. It is based on the author’s book İsmiyle Yaşamak (Living with this name), which presents the author’s interviews with forty-five non-Muslim natives about one of our most basic possessions: our names. Like my grandmother, Ender’s elder interlocutors were born during a tumultuous time. In the decades before and after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, both the state and the people living in those lands were busy negotiating who was or could become a Turk. [1] This negotiation is hardly over—the conversations in Ender’s book demonstrate that the debate over who is “local” or “foreign,” and according to which criteria, is ongoing. Markers such as “majority” or “minority” can hardly be understood in plain terms even among Muslim communities in Turkey—a Sunni Kurd could be a member of a minority group for ethnic and linguistic reasons, while an Alevi Turk could be considered part of one for religious reasons.

In presenting names as another frontier in the nationalization project of multiethnic nation-states like Turkey, each interview in Ender’s compilation leaves the reader with more questions, as each individual presents a unique history, revealing further complexities beyond the ethnic or religious traditions that often influence our identities: What are the roles of names in sustaining a minority consciousness? Which markers, alongside names, are used to erode minorities’ rights to civil inattention? How do minorities negotiate pressures for assimilation and acculturation as their communities dwindle in size?

Ender’s straightforward style in presenting her interviewees’ viewpoints also serves as a much-needed bridge for a gap in the documentation of the oral history of Turkey’s minority communities. While scholars and independent researchers have made significant strides in this arena in recent decades, Turkey’s diverse communities are in dire need of having their experiences recorded. [2]

Ender’s conversations touch upon sensitive moments endured by minorities during Turkey’s early history, as well as more recent events such the murder of Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in 2007 and the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident. Certain traumas that have become watershed moments in collective memory surface in the interviews like invisible threads connecting these diverse communities. For example, some conversations mention the “Citizen, Speak Turkish!” campaign, which began in 1928 and continued throughout the 1930s, targeting both Muslim and non-Muslim minorities who faced a fierce program of Turkification under the auspices of nation building in the new Turkish republic. [3]

As an oral history project, Ender’s book also shines a light on the symbolic influence that these moments in Turkey’s early history had in shaping the communal and national consciousness of the country’s minorities. Among Ender’s Armenian interviewees, memory of the Armenian Genocide of 1915 evokes a powerful emotional response. Almost all of them mention the tragedy and how it influenced their families. Other traumas that come up include the 1936 attacks on the Jewish communities of Thrace, the 1942 Varlık Vergisi (“Wealth Tax” levied on non-Muslim citizens), and the 1955 pogroms against non-Muslims in Istanbul.

Another symbol of minority-majority relations at both state and communal levels is the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). This peace treaty delineated the borders of the republic and overrode the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), which the Turkish national movement had rejected as a catastrophic division among foreign powers of what was left of the Ottoman Empire. The Treaty of Sèvres left a scar on the Turkish collective memory that has proven difficult to heal. Arguably, the rights granted to non-Muslim minorities as part of the Lausanne treaty contribute to the so-called Sèvres Syndrome whereby conspiracy theories often accuse minority communities of involvement in foreign influence and invasion. Even the most basic assertions of identity among minorities are often interpreted as attacks on the territorial integrity of Turkey. [4]

The freedom to name is one of those basic rights that many feared to exercise. The president of the Kadıköy Greek Orthodox Community Churches, Schools and Cemetery Foundation, Yorgo Istefanopulos, explained to Ender during their interview that at times, minority communities chose to use Turkish names to hide their identities. “During the period when the ‘Citizen, Speak Turkish!’ campaigns were ongoing, everybody denied their names. For example, we knew a Mr. Fedon. He instructed us to never call him by Fedon. Only Feridun! So we called him Mr. Feridun. His wife’s name, Triandafilia, means “rose” in Greek, so she became Mrs. Gül. Her sister Thedolosula became Şule. They didn’t want to use their own names. They were truly afraid.” [5]

That a discussion about something as innocous as a personal name conjures such painful moments in history is telling. Yet it would be a disservice to these communities to focus solely on the traumatic. Rather, İsmiyle Yaşamak celebrates the diversity and individuality of our names and our identities. Starting each interview with a pleasant and deeply personal discussion about the origin and meaning of her subjects’ names, Ender narrates communal and family histories. For example, after recounting the story of his being named after a character in a movie that his mother admired, Nino Varon explained that “Nino means storm. ‘El Niño’ is the name of a storm in Spanish. . . . Coupled with my last name, Nino Varon is very phonetic. Like an Italian fashion label or a French lighter company. . . . And for Turks it’s hard to categorize. People wonder—is he Greek, French, Italian, Armenian? The last thing they think of is that I am Jewish.” [6]

Ender’s study poignantly reveals, through honest discussions about our names, the multiplicity of identities that make up a person, beyond those of ethnicity or religious tradition. They embody the diversity—be it of age, gender, profession, life experience, or worldview—within each individual, community, and country.

Notes

[1] See Soner Cagaptay, Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk? (London: Routledge, 2006).

[2] For an overview, see Leyla Neyzi, “Oral History and Memory Studies in Turkey,” in Turkey’s Engagement with Modernity: Conflict and Change in the Twentieth Century, ed. Celia Kerslake, Kerem Öktem, and Philip Robins (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

[3] Senem Aslan, “‘Citizen, Speak Turkish!’: A Nation in the Making,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 13, no. 2 (2007): 245–272.

[4] Baskın Oran, Tűrkiye’de Azınlıklar: Kavramlar, Teori, Lozan, İç Mevzuat, İçtihat, Uygulama [Minorities in Turkey: Concepts, theory, Lausanne, legislation, case-law, implementation] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2008), 161.

[5] Yorgo İstefanopulos in Rita Ender, İsmiyle Yaşamak [Living with this name] (Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 2016), 281. All translations are my own.

[6] Nino Varon, in ibid., 215–216.

Living with This Name: “Foreign” Names of Turkey’s Non-Muslim Natives

Rita Ender

(Translated by Nathalie Alyon)

If you live in a country where you are afraid to admit that your name is Pierre, or Mahmoud, or Baruch, and where that state of affairs has lasted for four or perhaps for 40 generations; if you live in a country where you don’t even need to make such an “admission” because your allegiance is to be seen in the colour of your face, because you are a member of what in some places is called the ‘visible minorities’—if you live under any of these conditions, you don’t need long explanations to convince you that the words “majority” and “minority” don’t always belong to the vocabulary of democracy.

Amin Maalouf [1]

As Amin Maalouf eloquently writes, we minorities in Turkey who are made visible through our names indeed need no explanation to understand the limitations that accompany our imposed status. Just like our grandparents, we have long internalized the concept of being a minority and the fact that the so-called rights that accompany this status are not valued in the way that democracy or equality are and exist mostly on paper. We also don’t require an explanation of our rights, yet individuals we encounter in our day-to-day life constantly demand an explanation of our names. For example, if you don’t have a Turkish name and you live in Turkey, people ask, “Where are you from? Why do you have a foreign name? Where did your family come from?” As you try to prove that you’re not foreign at all, you often receive a small compliment, “You speak Turkish so well!” More often than not, a discussion on the ethnic implications of your name turns into a political discussion, and you find yourself taking responsibility for political decisions in other countries. İzel Rozental’s caricature (below) sums it up well. [2]

Figure 1. The cartoon depicts a group of children puzzled by the name of a peer. “What? What kind of name is Igal?” they ask. “Well… Igal is a Jewish name. I’m Jewish,” he responds. In bold, the children yell, “Booo! Death to Israel! Death to the USA!”. Reprinted by permission of İzel Rozental.

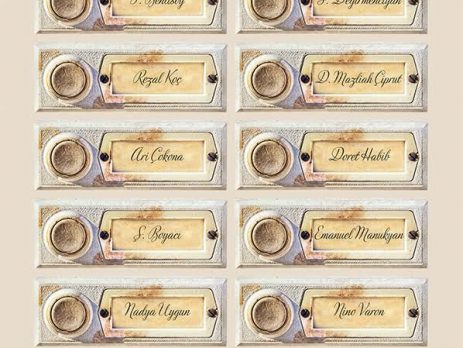

To understand the burdens imposed upon such individuals by society at large, I interviewed forty-five non-Muslim Turkish citizens who call Turkey home—Armenians, Greeks, Bulgarians, Jews, Assyrians, and Catholics. Each interview revealed two parallel storylines. The first described the origin and meaning of each person’s name: who had chosen their name, based on which traditions or under which circumstances, and why. The second narrative detailed each individual’s experience living in Turkey with a name that revealed a non-Muslim identity—which is often understood to be synonymous with a non-Turkish identity.

My interlocutors were made up exclusively of people who belong to non-Muslim minorities. Since the main goal of this project, originally published as a series of columns in the Armenian-Turkish bilingual newspaper Agos, was to examine the experiences of people with names that Turkish society sees as “foreign,” I did not interview members of non-Muslim minorities with obviously “Turkish” names. In other words, instead of interviewing an Armenian with the first name Murat or a Jew whose name is Selim, I spoke with an Armenian called Rafael and a Bulgarian named Elena. In choosing whom to interview, I also tried to give voice to a wide range of opinions by including people who belong to a variety of different age groups and professions and who have different sociopolitical stances. This diversity among my pool of interlocutors emphasizes the heterogeneity of these communities that are dwindling toward extinction.

These stories came together in the book İsmiyle Yaşamak (Living with this name), which alludes to a common Turkish expression that functions as a blessing for newborn babies. [3] When a baby is born in Turkey, good wishes are often conveyed through a common saying: İsmiyle yaşasın—May she (or he) live with her (or his) name. Friends and family pray that the newborn will embrace her or his given name and enjoy a long life using it. This blessing also charges newborns with the task of living a life that is deserving of their given name. These few words uttered in Turkish, a language that serves as the common tongue among Turkey’s diverse communities, form a small collective prayer.

Despite this small prayer, that which is sacred isn’t always shared among different communities. And when it comes to the act of naming, sometimes ideas of the sacred aren’t even agreed upon within the same community. Ari Çokona, a chemistry teacher at the Zografeion Lyceum who has translated several important works from Greek into Turkish, explained this with an example from his own baptism ceremony: members of the Greek Orthodox community in Turkey, who follow the rules of the Greek Orthodox Church, can only be baptized with a saint’s name. Because of this rule, Çokona’s father struggled to get him baptized. “They didn’t want to baptize a child with a name like ‘Aristotle.’ The rule is the same in Greece. If your name is Aristotle, they will baptize you as Georgios (Yorgos) and write Georgios Aristoteles on your ID card.”[4]

While Ari’s father didn’t want to bother with a saint’s name, Teodora Hacudi, a member of Izmir’s Greek Orthodox community, explained the importance of this custom to her: a Christian is protected by the saint whose name she or he carries. The custom is so important that

among Orthodox Greeks, the celebration of a name day takes precedence over a birthday. For example, people may not know the birthday of someone called Kosta, but without exception, they will commemorate his name day with a party: they invite everyone over, they give out food, treats, gifts . . . For us, name days are much more important than birthdays. My name day is the first Saturday that marks the beginning of the big fast [Lent]. [5]

In Judaism too newborns receive their names as part of a ritual. Boys, for instance, receive their names during the circumcision ceremony called the Brit Milah. Rabbi Albert Gershon from Istanbul explained the theological reasoning behind this practice:

Until his circumcision, our patriarch was known by the name Avram. Once he followed God’s commandment to circumcise, he became the first person to prove his loyalty and was told, “From now on your name will be Avraham, not Avram.” The rabbis took from this that a male child shall be named at his Brit Milah because according to the Torah it is during the circumcision that creation becomes fully complete. The mother, the father, and God are three partners in creation, shaping the child’s body, but creation is only completed on the eighth day when the circumcision takes place. Brit Milah means “covenant” precisely because it symbolizes that the covenant between Avraham and God will hold for generations to come. [6]

The rules according to which a newborn receives his name are as significant as the name itself. Most Turkish Jews—a majority of whom follow Sephardic traditions—name children after grandparents according to a particular order. If a family’s first born is a girl, she takes her paternal grandmother’s name. The second girl would take her maternal grandmother’s name and so forth. Ashkenazi Jews, however, do not name a baby after a living ancestor. As the president of the Ashkenazi Synagogue in Turkey, a minority within a minority, Benyamin Poluman, explained, “We only name our children after people who have passed away. When my daughter was born, my mother was still alive, so we didn’t name her Besi like her grandmother. We named her Brenda.” [7]

According to Bulgarian traditions, babies are named not by their biological parents but rather by their godparents. An administrator at the Bulgarian Exarchate Orthodox Church Foundation, Milko Pecatikov, traces this ancient ritual to Macedonian villages:

Our ancestors came from villages in Macedonia. According to the village tradition, a newborn couldn’t be named until its baptism. So people called newborns “baby” until the godparents named the child. And the biological parents had no say about this process. I even remember our elders describing how village children ran to the biological mother of a baby who had just been baptized to inform the mother of her child’s name and ask for baksheesh. Naturally, such traditions changed with time and emigration, but even until fairly recently a mother wouldn’t enter the church until her baby was baptized. She would wait outside until the baby was sanctified, and only after all rituals concluded would she enter the church and take her baby in her arms. [8]

All of these show that naming is not only about the individual—rather, it embodies thousands of years of communal traditions. Naming is a social act with symbolic and political significance. As sociologist Arus Yumul explains, societal aspects of naming are meaningful:

In the biblical story of creation, God says, “Let there be light,” and there is light. God then bestows Adam with the power to name, and he [Adam] dominates his realm by naming animals and plants. We can observe the same power game on the societal level. For instance, the names a particular community uses to refer to itself often differ from the names given to them by outsiders. Humans divide the world into parts and name them. Maps present a static reality, as if time has halted. It is not possible to deduce which societies have come and gone from a specific land by looking at maps—they don’t provide such information. A new sovereign erases the past and renames the land. [9]

Precisely because naming is related to a community, names often have different connotations within different groups. For Istanbulites, the name Despina—one of the names of the Virgin Mary—evokes Madame Despina, the owner of a famous tavern in Istanbul. The surname Manukyan is reminiscent of the ethnic Armenian Matild Manukyan, who made such a fortune managing brothels in Istanbul that she became a top taxpayer in the 1990s and was given commendations by the state.

Alongside their associations in popular memory, names carry symbolic significance. Mt. Ararat, believed to be the site where Noah’s ark landed after the Flood, is a massive mountain near the Turkish-Armenian border. As a personal name, Ararat symbolizes the grandeur of this mountain. Ararat Şekeryan, a PhD student in comparative literature, describes Mt. Ararat, a national symbol in Armenia, as “a most dominant character in Yerevan,” Armenia’s capital city. Ararat didn’t see his namesake with his own eyes until he was in his late twenties. When he finally visited Yerevan, he realized that “Ararat is indeed everywhere! The street artist paints Ararat; it’s on cookie packages and on banknotes . . . Walk on any street in Yerevan, turn a corner and there it is, in front of you. And it’s so beautiful with its snowy peaks, protecting the country.” Indeed, Ararat’s namesake evokes a feeling of patriotic pride for some, as if the mountain declares, “We were here, we are here, our roots are here.” [10]

It’s important to be accepted where you’ve laid down roots. For this reason people often refer to the past when explaining their identities and feel the need to provide historical information or to correct myths about their communities. For those minorities in Turkey who carry “foreign” names, this daily, repetitive task can become irritating. “People don’t seem to understand,” says Teodora Hacudi, explaining her frustration:

They start with a compliment on how well I speak Turkish. When I state that I’m a Turkish citizen born in this country, they follow up with a question inquiring as to when “we” arrived in Turkey. We never arrived, I say, because we were always here. My mother, my father, my grandfather, they are all citizens of Turkey. But they don’t give up. “Before then?” they press on. Before then, we were Ottoman, and before then, Byzantine . . . They can neither seem to understand that we belong to this land nor that a citizen of this country can be a non-Muslim. [11]

Those individuals who belong to the majority and view minorities as “foreigners” or “local foreigners” cannot be convinced otherwise, even after they learn the history of the vast number of different ethnic and religious groups who are native to this land. As if to emphasize our differences, they devise linguistic “solutions” to our status. For example, non-Muslim women in Turkey are often addressed with the title “bayan” or “madam,” instead of the Turkish equivalent “hanım.” Similarly, non-Muslim men are often addressed with the title “bay” instead of “bey.” Even though bayan and hanım are synonyms, bayan is reserved for non-Muslims. This discrimination frustrates Gila Benmayor, a Turkish journalist of Jewish descent:

I scold people who ask me if I’m a foreigner. . . . It makes me angry when people call me “Bayan Gila” instead of “Gila Hanım.” . . . And they don’t call Turkish [Muslim] women bayan. I also find it strange that minorities also use this title among themselves. Every time it happens I snap: “Don’t call me Bayan Gila, call me Gila Hanım!” [12]

Why do people feel the need to verify whether you are a foreigner or a native? Why do they strive to gauge the level of your connection to your country through your religious or ethnic identity? And why do minorities find themselves defending their native status in the land where they were born, live, and die?

Like the others I interviewed, Yudit Namer spent many years having to provide answers to those who question her identity. A psychologist by profession, she believes that minority status evokes a curiosity: “The majority sometimes feels like it has a right to meddle in the personal lives of the minority. Minorities seem like objects displayed at a zoo for the enjoyment of the majority.”

Namer explained the phenomenon through an analogy from her own life. As a psychotherapist she works with individuals who identify as LGBTQ. Often, when a new acquaintance first hears about this part of her professional life, they ask whether she is a lesbian. Namer finds a parallel with this invasive inquiry into her personal sphere. She replies with a question of her own: “Did I ask you who you sleep with? We don’t know each other! What makes you feel comfortable enough to question my personal [sexual] identity?” In Namer’s experience, the majority grants itself a collective right to inquire and intrude into the intimate identities of minorities. “It seems to me that people believe that by virtue of our status as a minority, we relinquish our right to privacy in this regard.” [13]

Not only do minorities have rights to privacy just like anybody else, they also have special rights as minorities, which have been and continue to be violated repeatedly. Just as individuals inherit their names, so too do they inherit these injustices. For many Armenians, this is the dark and painful history of the Armenian Genocide in 1915. Zakarya Mildanoğlu is an architect and researcher who inherited his uncle’s name. His father was born in 1903 in Yozgat to a family of six siblings, none of whom Zakarya met.

Out of all of his brothers, only my father survived. He was saved by missionaries in Kayseri in 1915. For some time, he stayed in the Talas American College and then traveled all over looking for his family. When he reached about the age of 25-30, he grew tired of the search and married my mother. They had four boys and two girls, all of whom he named after his brothers and sisters. My name is my uncle’s name, my uncle Zakarya. [14]

Mildanoğlu didn’t want to talk further about either his uncle’s disappearance or what happened in 1915. “I don’t talk about this much. I don’t want to. It’s not that I’m stuck back in time, but as Hrant [Dink] used to say, ‘Where are my fathers, my grandfathers?’ [15] It’s like that. Where are my uncles? Where are my five uncles? They existed. Their names are recorded in population registries, but where are they?” [16]

Communications consultant Doret Habib inherited her name from her paternal grandmother, Doreta Aviyente, who lived in Kırklareli during the 1934 pogrom known in Turkish as the “Thrace Events,” perpetrated against the Jews of Thrace. Doret never met her grandmother but learned her story from history books. She describes her grandmother as an “interesting personality, an active woman. I’m told she was a very strong, fearless, opinionated woman. She was a graceful woman who protected her family and community.” [17]

As in Doret’s case, these intimate ties of memory and family history often focus particularly on women, on the intimate rather than the public sphere. For this reason it is befitting to remember philosopher Ioanna Kuçuradi’s words, “Whenever I go somewhere where I am not acquainted with the local naming customs, I ask people what their mothers called them. A mother is always the most intimate to a person. Mothers know best how to pronounce their children’s names.” [18]

May our names always be pronounced correctly and our right to privacy be respected.

Notes

[1] Amin Maalouf, In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong, trans. Barbara Bray (New York: Penguin, 2003), 153.

[2] İzel Rozental, Şalom, July 26, 2006.

[3] Rita Ender, İsmiyle Yaşamak [Living with this name] (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2016). These interviews were initially published between March 2015 and March 2016 in the Armenian bilingual weekly newspaper Agos, published in Istanbul, Turkey.

[4] Ari Çokona, interviewed in Ender, İsmiyle Yaşamak, 40.

[5] Teodora Hacudi, ibid., 262.

[6] Rabbi Albert Gershon, ibid., 27.

[7] Benyamin Poluman, ibid., 67.

[8] Milko Pecatikov, ibid., 197.

[9] Arus Yumul, ibid., 58.

[10] Ararat Şekeryan, ibid., 34.

[11] Teodora Hacudi, ibid., 263.

[12] Gila Benmayor, ibid., 132.

[13] Yudit Namer, ibid., 286.

[14] Zakarya Mildanoğlu, ibid., 288.

[15] Hrant Dink served as the editor-in-chief of the Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos from its founding in 1996 until his death in 2007. Owing to his unwavering stance and declarations regarding the Armenian Genocide and minority rights, he became a public figure and was murdered in front of the Agos offices in Istanbul on January 19, 2007.

[16] Zakarya Mildanoğlu, in Ender, İsmiyle Yaşamak, 290.

[17] Doret Habib, ibid., 87.

[18] Ioanna Kuçuradi, ibid., 141.

Leave a Reply