Being Frank? Discovering My Frankist Roots

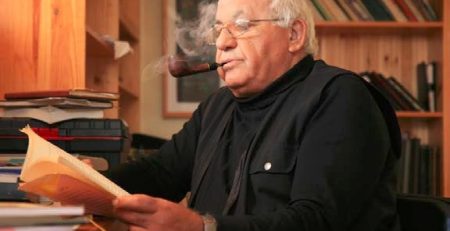

Jaan Kaplinski’s ancestors include Estonians, Poles, Jews, Tartars, and Greeks. He was born in 1941 and grew up in the old university town of Tartu (Dorpat) in Estonia, where he studied linguistics. He has written some eight hundred poems, two collections of short stories, a novel, and many essays and articles. Several of his books have been translated into English, and one of them– Ice and the Titanic– into Hebrew. From 1992 to 1995 he was a deputy in the first democratically elected parliament of Estonia, after the country had regained its independence in 1991. He has traveled widely in Europe, Asia, and America. He has a large family and lives, most of the time, in an old farmhouse near Tartu.

Being Frank?

by Zohar Kohavi

From the beginning of my involvement in the history of the Frankist movement, I understood the special combination of two factors that were at work in it and that shaped it in the generation before the French Revolution and in the generation after it. These two factors are the leaning toward esoteric and kabalistic schools of thought, on the one hand, and the leaning toward the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) and the enlightened (maskilic) frame of mind, on the other. Both trends become intertwined and lend this movement a strange and wondrous duality.[i]

Jacob Frank and his community, which apparently included Jews of every social class and occupation, were actually Dönme, that is, secret Sabbateans, who called themselves Sabbatean Believers. That is how they were perceived by many Jews, and indeed the name “Frankists” came into use only in the nineteenth century. Many of the rites Frank introduced–such as profanation of the Sabbath; abstention from fasting, even on Yom Kippur; and incest–subverted Jewish customs and the social order, although one must not infer from this that Frankism was a marginal phenomenon.

From the story of Jacob Frank’s life or, to be more precise, of his adventures, emerges a portrait of a subversive and unrestrained character, charismatic and quick-thinking, mythic and ecstatic, dark and enigmatic, and at the same time, narcissistic, aggressive, coarse, sly, and deceptive. These characteristics suggest a very complex personality, but at the same time they appear to coexist with each other. Frank’s biography reflects a considerable gap between his outward liminality and his inner identity. Another characteristic, perhaps the one that joins together all the diverse aspects of his personality, is movement. Frank traveled around the world, moving among languages (between Yiddish and Ladino, inter alia); moving among clerics and among rulers (both male and female); moving between religions, and also, in keeping with his teachings, moving between worlds – between the concealed world and the revealed world, and between the old world and the new world that he wished to represent. When one learns of his “(mis)deeds,” one cannot but be amazed by his ease of movement and by the impression that he moved in the world effortlessly, as if he were coasting. Also, one cannot help but notice that such movement and action are characteristic of both historical and fictional figures, in the past and in the present, who are fearless or unable to feel fear. Such figures are rooted in a world without borders, and this makes one doubt their autonomy (which can exist only in the presence of borders).

Jacob Frank was born in Korolivka, Podolia, in 1726, apparently to a Sabbatean family. He spent his childhood with his family in Czernowitz and in Sniatyn; later he lived in Bucharest, where he earned a living as a merchant. From there he moved to the Balkans, arriving in Izmir and Thessaloniki, cities in which many Dönme lived. In 1752 he married in Nikopol, Bulgaria. Between 1752 and 1755 he started claiming that he was the incarnation of Shabbetai Zevi and that he was the Messiah. In 1755, Frank and his followers returned to Poland, where he presented himself as the Messiah and disseminated his teachings and subversive rites. In 1756, for example, Frank aroused a scandal in Landskron when he conducted an antinomian religious-sexual rite that resulted in the arrest of the participants (Frank was released, apparently because he was a Turkish national). This scandal led to the excommunication of Frank and his community in 1757 by the rabbis of Brody, forcing his persecuted followers to flee to the protection of Bishop Dembowski in Kamianets-Podilskyi. Under the auspices of the bishop, an eight-day disputation between the Frankists and the rabbis was held. In October 1757, the bishop ruled in favor of the Frankists and ordered, inter alia, that the rabbis be punished and that all volumes of the Talmud be burned. The burning of the books was interrupted by an unexpected twist in the plot: the sudden death of the bishop. This was seen as divine intervention, and consequently the persecution of Frank’s community was renewed. By then Frank was already back in Turkey. In 1757, he converted to Islam along with many of his believers (as had Shabbetai Zevi in his day), perhaps because of his desire to receive Turkey’s protection after all the persecution the Frankists had suffered. In 1758, King August III of Poland granted his protection to Frank and his followers and thus enabled them to return to Iwania, a town in Podolia. During this period Frank consolidated his leadership of the sect, introduced organizational rules, developed his doctrine, and claimed that all religions were nothing but way stations through which the believer must pass before arriving at true belief, like the peel of a fruit through which one must pass before the fruit can be eaten. At this time Frank seems to break away from Sabbatean theology.

In 1759, Frank and his followers turned to the archbishop of Lvov and asked to convert to Christianity but to keep several Jewish practices, such as engaging in study of the Kabala and abstaining from eating pork. The church rejected the conditions but agreed to accept the Frankists, despite rabbis’ warnings that the sect was rooted in Sabbatean belief. Prior to the conversion, a public disputation between the Frankists and the rabbis took place regarding the principles of Jewish faith, such as the Frankist claim that all the biblical prophecies concerning the coming of the Messiah had already been fulfilled and that the Messiah was the true God. They also debated the blood libel according to which the Talmud requires Jews to use the blood of Christians. The Frankists sided with the arguments of the church, largely because they wanted to be accepted by the church. The disputation ended indecisively but led to the conversion of hundreds of Frank’s faithful (according to tradition, thousands converted), including Frank himself. A short while later, in the beginning of February 1760, Frank was arrested after the church learned that the Frankists’ conversion had not been sincere and that he and his followers saw him as the living incarnation of God. Frank was exiled to the Częstochowa monastery, where he remained some thirteen years in relatively comfortable conditions. During this period he sent emissaries to the Greek Orthodox Church and to the Russian authorities. In 1762, his wife joined him and a group of his faithful was allowed to live near the monastery and conduct orgiastic rites. In August 1772, following the Russian conquest of the area, Frank was released and until 1786 he lived in Brno, Moravia, under the protection of the authorities.

In Brno, Frank enlarged his community and turned it into a court of sorts; he did the same also in Offenbach, near Frankfurt, where he settled in 1787. His court took on a military character. His followers wore a uniform and underwent continuous military training, strict discipline was enacted, and violations entailed severe punishment, including imprisonment in a jail within the court. During this period many Sabbateans who lived in Moravia joined Frank. In Brno and Offenbach he also wrote The Collection of Words of the Lord (known also as The Sayings of the Lord). The book was actually transcribed by several of Frank’s longtime disciples, and it includes hundreds of sayings concerning stories, memories, and proverbs, and kabalistic and mythical traditions. Maciejko argues that “Frank went farther than his predecessors: His bizarre theosophy is an attempt to look at what one is forbidden to look at, to return to the sources that preceded the sources of the overt religion. The Sayings of the Lord, like Hegel’s Science of Logic, though in a very different way, is an attempt to peer into the workings of God’s thought before he created the world.”[1] Frank died in Offenbach on December 10, 1791.

***

Kaplinski’s point of departure, and the framework of his text, is the story of the discovery of his Frankist roots and his family links to Frank. But in the course of this personal discovery, Kaplinski attains many broader insights into Frank, his aspiration to reach “the naked truth,” and Frankism’s taboo status to this day. Kaplinski also addresses the criticism of the rites Frank conducted and argues that sometimes the criticism dwells on the sexual license so that the license overshadows the ritualistic manner in which sex was used.

Kaplinski points out the connection between the Frankists, Christianity, and Islam. As I have already noted, Frank converted twice and apparently even sought to draw close to the Russian Orthodox Church. It is also known that the views and practices of Frank and his disciples did not change as a consequence of their conversion to Christianity, and Kaplinski points out that Frank’s views did not change as a result of his conversion to Islam. Frank related to Christianity and Islam, and to religious establishments in general, as bodies through which he could advance his plans. In this sense, one may compare the relations between Frank and these institutions, to which Kaplinski refers, to the relations between a parasite and its host. Like cultural phenomena, the parasite and its “interests” must be examined in the environment in which it exists.

As Kaplinski writes, we do not have much information about Frank’s ties to Islam and to heterodox factions in Islam. He notes the similarity between the Frankists and the Bektashi (a Sufi order) and argues that they share a mystical tradition. According to Kaplinski, to fully understand these phenomena one must study their mutual connections. In this he seems to be complementing, albeit from another direction, Maciejko’s argument that “Frank’s syncretistic motif did not lead to the addition to, or enrichment, of one religion by means of the elements of the other religion, but rather to a conscious merging of them all.”[2]

Rachel Elior argues that Frank, in his consciousness, sayings, words, deeds, and visions created “a lawless reality that constitutes a new world that is linked to that of Adam in the Garden of Eden, a world before sin, that precedes the distinction between good and evil, between taboo and permission, and between life and death. He explained this anomic and anarchist reality by linking it to the Sabbatean revolution, which was based on the coming of the Messianic age, and which is nothing but a return to the beginning of days, since the Messiah is identified with Adam.”[3] I do not think that Kaplinski would object to this argument, which indicates hubris (and I have already noted that in a certain sense Frank was totally fearless). Nevertheless, note that Kaplinski emphasizes other sides of Frank’s teachings and deeds that usually go unremarked; thus, for example, he argues that by founding his tiny state, Frank became the herald of Zionism.

Kaplinski is a poet, and that is evident in his text. His moves are silent, almost covert; his writing advances naturally; and he does not tend to wordiness. He writes as if he were holding a power-steering wheel, a wheel with which the slightest motion generates significant movement. And indeed, reading Kaplinski’s text is like traveling through a historico-cultural landscape. Some may disagree with him, but his discussion is not historical, and Kaplinski does not seek to posit an argument. If we return to the metaphor of travel, the goal of the experience of travel that he offers us is not to bring us to a final destination but rather to expose us to various landscapes in the “Frankist land.” The smooth writing engulfs the reader in the warm comfort of travel, but one must stay awake and pay attention to the nuances that appear in the text seemingly casually; nod off, and the landscape passes one by.

Notes

[i] Gershom Scholem, “The Career of a Frankist: Moses Dobruschka and his Metamorphoses,” in Studies and Texts Concerning the History of Sabbetianism and its Metamorphoses (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1974), 141.

[1] Pawel Maciejko, “Dangers and Pleasures of Religious Syncretism: On the Frankist Doctrine of Conversion,” in ‘New Old Things’: Myths, Mysticism and Controversies, Philosophy and Halacha, Faith and Ritual in Jewish Thought through the Ages, ed. Rachel Elior (Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought, Vol. XXIII, 2011), 2:275.

[2] Ibid, 257.

[3] Rachel Elior, “Jacob Frank and His Book the Sayings of the Lord: Religious Anarchism as a Restoration of Myth and Metaphor,” in The Sabbatian Movement and Its Aftermath: Messianism, Sabbatianism and Frankism, ed. Rachel Elior (Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought, Vol. XVII, 2001), 2:487.

- + About the Author

-

Jaan Kaplinski’s ancestors include Estonians, Poles, Jews, Tartars, and Greeks. He was born in 1941 and grew up in the old university town of Tartu (Dorpat) in Estonia, where he studied linguistics. He has written some eight hundred poems, two collections of short stories, a novel, and many essays and articles. Several of his books have been translated into English, and one of them– Ice and the Titanic– into Hebrew. From 1992 to 1995 he was a deputy in the first democratically elected parliament of Estonia, after the country had regained its independence in 1991. He has traveled widely in Europe, Asia, and America. He has a large family and lives, most of the time, in an old farmhouse near Tartu.

- + Analysis

-

Being Frank?

by Zohar Kohavi

From the beginning of my involvement in the history of the Frankist movement, I understood the special combination of two factors that were at work in it and that shaped it in the generation before the French Revolution and in the generation after it. These two factors are the leaning toward esoteric and kabalistic schools of thought, on the one hand, and the leaning toward the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) and the enlightened (maskilic) frame of mind, on the other. Both trends become intertwined and lend this movement a strange and wondrous duality.[i]

Jacob Frank and his community, which apparently included Jews of every social class and occupation, were actually Dönme, that is, secret Sabbateans, who called themselves Sabbatean Believers. That is how they were perceived by many Jews, and indeed the name “Frankists” came into use only in the nineteenth century. Many of the rites Frank introduced–such as profanation of the Sabbath; abstention from fasting, even on Yom Kippur; and incest–subverted Jewish customs and the social order, although one must not infer from this that Frankism was a marginal phenomenon.

From the story of Jacob Frank’s life or, to be more precise, of his adventures, emerges a portrait of a subversive and unrestrained character, charismatic and quick-thinking, mythic and ecstatic, dark and enigmatic, and at the same time, narcissistic, aggressive, coarse, sly, and deceptive. These characteristics suggest a very complex personality, but at the same time they appear to coexist with each other. Frank’s biography reflects a considerable gap between his outward liminality and his inner identity. Another characteristic, perhaps the one that joins together all the diverse aspects of his personality, is movement. Frank traveled around the world, moving among languages (between Yiddish and Ladino, inter alia); moving among clerics and among rulers (both male and female); moving between religions, and also, in keeping with his teachings, moving between worlds – between the concealed world and the revealed world, and between the old world and the new world that he wished to represent. When one learns of his “(mis)deeds,” one cannot but be amazed by his ease of movement and by the impression that he moved in the world effortlessly, as if he were coasting. Also, one cannot help but notice that such movement and action are characteristic of both historical and fictional figures, in the past and in the present, who are fearless or unable to feel fear. Such figures are rooted in a world without borders, and this makes one doubt their autonomy (which can exist only in the presence of borders).

Jacob Frank was born in Korolivka, Podolia, in 1726, apparently to a Sabbatean family. He spent his childhood with his family in Czernowitz and in Sniatyn; later he lived in Bucharest, where he earned a living as a merchant. From there he moved to the Balkans, arriving in Izmir and Thessaloniki, cities in which many Dönme lived. In 1752 he married in Nikopol, Bulgaria. Between 1752 and 1755 he started claiming that he was the incarnation of Shabbetai Zevi and that he was the Messiah. In 1755, Frank and his followers returned to Poland, where he presented himself as the Messiah and disseminated his teachings and subversive rites. In 1756, for example, Frank aroused a scandal in Landskron when he conducted an antinomian religious-sexual rite that resulted in the arrest of the participants (Frank was released, apparently because he was a Turkish national). This scandal led to the excommunication of Frank and his community in 1757 by the rabbis of Brody, forcing his persecuted followers to flee to the protection of Bishop Dembowski in Kamianets-Podilskyi. Under the auspices of the bishop, an eight-day disputation between the Frankists and the rabbis was held. In October 1757, the bishop ruled in favor of the Frankists and ordered, inter alia, that the rabbis be punished and that all volumes of the Talmud be burned. The burning of the books was interrupted by an unexpected twist in the plot: the sudden death of the bishop. This was seen as divine intervention, and consequently the persecution of Frank’s community was renewed. By then Frank was already back in Turkey. In 1757, he converted to Islam along with many of his believers (as had Shabbetai Zevi in his day), perhaps because of his desire to receive Turkey’s protection after all the persecution the Frankists had suffered. In 1758, King August III of Poland granted his protection to Frank and his followers and thus enabled them to return to Iwania, a town in Podolia. During this period Frank consolidated his leadership of the sect, introduced organizational rules, developed his doctrine, and claimed that all religions were nothing but way stations through which the believer must pass before arriving at true belief, like the peel of a fruit through which one must pass before the fruit can be eaten. At this time Frank seems to break away from Sabbatean theology.

In 1759, Frank and his followers turned to the archbishop of Lvov and asked to convert to Christianity but to keep several Jewish practices, such as engaging in study of the Kabala and abstaining from eating pork. The church rejected the conditions but agreed to accept the Frankists, despite rabbis’ warnings that the sect was rooted in Sabbatean belief. Prior to the conversion, a public disputation between the Frankists and the rabbis took place regarding the principles of Jewish faith, such as the Frankist claim that all the biblical prophecies concerning the coming of the Messiah had already been fulfilled and that the Messiah was the true God. They also debated the blood libel according to which the Talmud requires Jews to use the blood of Christians. The Frankists sided with the arguments of the church, largely because they wanted to be accepted by the church. The disputation ended indecisively but led to the conversion of hundreds of Frank’s faithful (according to tradition, thousands converted), including Frank himself. A short while later, in the beginning of February 1760, Frank was arrested after the church learned that the Frankists’ conversion had not been sincere and that he and his followers saw him as the living incarnation of God. Frank was exiled to the Częstochowa monastery, where he remained some thirteen years in relatively comfortable conditions. During this period he sent emissaries to the Greek Orthodox Church and to the Russian authorities. In 1762, his wife joined him and a group of his faithful was allowed to live near the monastery and conduct orgiastic rites. In August 1772, following the Russian conquest of the area, Frank was released and until 1786 he lived in Brno, Moravia, under the protection of the authorities.

In Brno, Frank enlarged his community and turned it into a court of sorts; he did the same also in Offenbach, near Frankfurt, where he settled in 1787. His court took on a military character. His followers wore a uniform and underwent continuous military training, strict discipline was enacted, and violations entailed severe punishment, including imprisonment in a jail within the court. During this period many Sabbateans who lived in Moravia joined Frank. In Brno and Offenbach he also wrote The Collection of Words of the Lord (known also as The Sayings of the Lord). The book was actually transcribed by several of Frank’s longtime disciples, and it includes hundreds of sayings concerning stories, memories, and proverbs, and kabalistic and mythical traditions. Maciejko argues that “Frank went farther than his predecessors: His bizarre theosophy is an attempt to look at what one is forbidden to look at, to return to the sources that preceded the sources of the overt religion. The Sayings of the Lord, like Hegel’s Science of Logic, though in a very different way, is an attempt to peer into the workings of God’s thought before he created the world.”[1] Frank died in Offenbach on December 10, 1791.

***

Kaplinski’s point of departure, and the framework of his text, is the story of the discovery of his Frankist roots and his family links to Frank. But in the course of this personal discovery, Kaplinski attains many broader insights into Frank, his aspiration to reach “the naked truth,” and Frankism’s taboo status to this day. Kaplinski also addresses the criticism of the rites Frank conducted and argues that sometimes the criticism dwells on the sexual license so that the license overshadows the ritualistic manner in which sex was used.

Kaplinski points out the connection between the Frankists, Christianity, and Islam. As I have already noted, Frank converted twice and apparently even sought to draw close to the Russian Orthodox Church. It is also known that the views and practices of Frank and his disciples did not change as a consequence of their conversion to Christianity, and Kaplinski points out that Frank’s views did not change as a result of his conversion to Islam. Frank related to Christianity and Islam, and to religious establishments in general, as bodies through which he could advance his plans. In this sense, one may compare the relations between Frank and these institutions, to which Kaplinski refers, to the relations between a parasite and its host. Like cultural phenomena, the parasite and its “interests” must be examined in the environment in which it exists.

As Kaplinski writes, we do not have much information about Frank’s ties to Islam and to heterodox factions in Islam. He notes the similarity between the Frankists and the Bektashi (a Sufi order) and argues that they share a mystical tradition. According to Kaplinski, to fully understand these phenomena one must study their mutual connections. In this he seems to be complementing, albeit from another direction, Maciejko’s argument that “Frank’s syncretistic motif did not lead to the addition to, or enrichment, of one religion by means of the elements of the other religion, but rather to a conscious merging of them all.”[2]

Rachel Elior argues that Frank, in his consciousness, sayings, words, deeds, and visions created “a lawless reality that constitutes a new world that is linked to that of Adam in the Garden of Eden, a world before sin, that precedes the distinction between good and evil, between taboo and permission, and between life and death. He explained this anomic and anarchist reality by linking it to the Sabbatean revolution, which was based on the coming of the Messianic age, and which is nothing but a return to the beginning of days, since the Messiah is identified with Adam.”[3] I do not think that Kaplinski would object to this argument, which indicates hubris (and I have already noted that in a certain sense Frank was totally fearless). Nevertheless, note that Kaplinski emphasizes other sides of Frank’s teachings and deeds that usually go unremarked; thus, for example, he argues that by founding his tiny state, Frank became the herald of Zionism.

Kaplinski is a poet, and that is evident in his text. His moves are silent, almost covert; his writing advances naturally; and he does not tend to wordiness. He writes as if he were holding a power-steering wheel, a wheel with which the slightest motion generates significant movement. And indeed, reading Kaplinski’s text is like traveling through a historico-cultural landscape. Some may disagree with him, but his discussion is not historical, and Kaplinski does not seek to posit an argument. If we return to the metaphor of travel, the goal of the experience of travel that he offers us is not to bring us to a final destination but rather to expose us to various landscapes in the “Frankist land.” The smooth writing engulfs the reader in the warm comfort of travel, but one must stay awake and pay attention to the nuances that appear in the text seemingly casually; nod off, and the landscape passes one by.

Notes

[i] Gershom Scholem, “The Career of a Frankist: Moses Dobruschka and his Metamorphoses,” in Studies and Texts Concerning the History of Sabbetianism and its Metamorphoses (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1974), 141.

[1] Pawel Maciejko, “Dangers and Pleasures of Religious Syncretism: On the Frankist Doctrine of Conversion,” in ‘New Old Things’: Myths, Mysticism and Controversies, Philosophy and Halacha, Faith and Ritual in Jewish Thought through the Ages, ed. Rachel Elior (Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought, Vol. XXIII, 2011), 2:275.

[2] Ibid, 257.

[3] Rachel Elior, “Jacob Frank and His Book the Sayings of the Lord: Religious Anarchism as a Restoration of Myth and Metaphor,” in The Sabbatian Movement and Its Aftermath: Messianism, Sabbatianism and Frankism, ed. Rachel Elior (Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought, Vol. XVII, 2001), 2:487.

Discovering my Frankist Roots

Jaan Kaplinski

I was born in Estonia of an Estonian mother and a Polish father. As for my father, Jerzy, I really never met him: He was arrested when I was six months old and later perished in a gulag labor camp. I grew up as an Estonian without knowing much of my father. I suppose even my mother didn’t know he had had Jewish ancestors. Much later I was told by an older friend of mine, a professor of Old Testament theology, that the family name Kaplinski was most probably Jewish. He said Kaplinskis were Jews living on church-owned lands in Poland. He was only partly right: Most, if not all Kaplinskis, like Kaplins, Kaplans, Kaplanskis, and Kaplens are originally Cohens, members of the extended priestly family. But this is something I found out much later, as a middle-aged man. I’m sure my father knew much about his ancestors; he was even fluent in Yiddish, but he was wise enough not to talk about it in the 1930s. Still, there had been rumors about him being a Jew; at least once he was attacked in the street by some nationalist thugs, and one of his acquaintances had called me this “Jewish boy.”

I was somewhat puzzled by what the professor had told me about my family name, but didn’t care too much about it. I studied linguistics and tried to learn some Arabic and Hebrew. And purely by chance, I bought a book from an elderly man liquidating his mostly esoteric-theosophic library. This was Erotik der Kabbala by the once well-known author Jiři Langer, a friend of Franz Kafka. There I read for the first time about Jacob Frank and his sect. Like most of what is written about Frank and the Frankists, Langer’s book is somewhat biased. For him, Frank’s understanding of the Kabala was erroneous and he misled his followers. Like most writers, Langer too pays a lot of attention to the orgiastic rites of the Frankists, interpreting them as the practice of free group sex, no different from similar practices of the twentieth-century hippies and other ancient and modern adepts of free love. Here, I cannot completely agree. But on this topic, a bit later.

In the late 1990s I was given a book in Polish about my great-granduncle, Polish painter and emigrant political activist Leon Kapliński, where I found out that our family had really been Frankist, like many other families of Polish intellectuals. And during a visit to the United States in 1999 I was able to spend some time in the libraries at Stanford and Columbia universities. It was there that I found that our family was quite closely connected with Jacob Frank himself. I have strong reasons to believe that our direct ancestors were the father-in-law and brother-in-law of Frank—the rabbi Toviah Cohen from Nikopol, in present-day Bulgaria, and his son Jacob, brother of Hannah, Frank’s wife. Here, I have a different view from that of the man I consider to be the most competent contemporary scholar in the field of Frankism—the Polish researcher Jan Doktór. In his opinion, Jacob Kapliński was the husband of Frank’s sister, a Sabbatean erudite, Yehuda Levy Tova.[1] I have no information indicating that a Levy descendant could have had the family name Kaplinski. And in a Polish bookit is written that Frank married a woman from the priestly family of Aharon.[2] But here, I haven’t been able to find out as much as I would have wished. I have no close relatives in Poland, and even nowadays, people do not want to speak or even to know about their Frankist ancestors. And sometimes they are harshly reminded of them, as happened in the 1930s to my distant relative Tadeusz Żeleński (whose pen name was Boy), a translator and controversial publicist. A critic found “ghetto spirit” in Boy’s writings, although his ancestors had converted nearly two hundred years before. And the question of the renowned Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz’s possible Frankist background is still largely taboo. My great-great-grandmother’s maiden name was Magdalena Brzezińska. I once wrote to Zbigniew Brzeziński, whom I had met earlier, asking whether we might be related; he answered that he didn’t know much about his ancestors, who had probably come from somewhere in Volhynia… Our family archives went up in flames during the war, and thus I know little about my distant ancestors, except the fact that my grandfather’s great-grandfather, Eliasz Adam Kapliński, tried to organize a Frankist congress in Karlsbad in 1823.[3]

Although, as I have written above, I grew up without any knowledge of my ancestors’ ideas and doings and with a very vague idea of Judaism, even without knowing it I had some contact with ideas possibly born under the influence of Frankism and Sabbateanism. As a student of linguistics, I discovered the philosophical works of Fritz Mauthner, who invented the expression “critique of language,” which was later developed by Wittgenstein and other philosophers. Much later I discovered that Mauthner’s grandfather had served in Frank’s court in Offenbach, and that there had been some relics—including a portrait of Eva Frank, Jacob’s daughter—in the possession of the Mauthner family. As Mauthner writes, some Frankist emissaries later took these things away, as seems to have been the case in other families too. I can well understand the desire of upper-middle-class Poles to hide their origins, but it is hard for me to understand why the last Frankists willingly or unwillingly helped them in this. Could we take it as a special case of what the Islamic sectarians, first of all the Ismailiyyas, call taqiyya—a tactic to hide some controversial points of their belief? And certainly there were many controversial aspects in the teaching and activities of Jacob Frank and his entourage. His rhetoric is sometimes fiercely negativistic, and his sexual practices are blatantly unconventional: There were indeed things people integrated into the normal bourgeois life of the mid-nineteenth century that they had good reasons to hide and/or forget.

There are publications on Jacob Frank in the United States and Poland; the book by Alexander Kraushar on him has been published in English translation.[4] Unfortunately, the best studies on Frank and Frankism are by the Polish scholar Jan Doktór and seem to have been ignored by the academic world in America. Dr. Doktór has published a critical edition of the The Sayings of the Lord in Polish and some books about Frank.[5] While we know much about Frank’s relations with the Catholic Church, there is not much clarity about Frank’s contacts with Islam. His conversion to Islam seems to have had little impact on his views, although several papers, among them Gershom Scholem’s article on the Dönme, mention close connections between some Sufis from the Bektashi order of dervishes and Jacob Frank, as had been the case with leading Sabbateans. This fact suggests that it would be worthwhile to find out more about the parallels between the Sabbatean-Frankist teaching and practices and those of the Bektashis. Unfortunately, as far as I know, no one has done this, and I am not able to do it. Still, an academic from a Bektashi family in Turkey has told me what she could recall from what one of the eminent Bektashi spiritual leaders, a family friend, had told her when she was still an adolescent. I quote from my diary from December 10, 1994: “There are no more true sheikhs among the Bektashis. One of them whom she knew best had been a merry person, always laughing. He had said that one must get rid of religion (dīn), the outer shell, but also of faith (īmān). He had sometimes read the Bible, loving especially stories that made him laugh as, for example, David dancing in front of the Ark of the Covenant. In his opinion, the three ‘abrahamic’ religions are of equal value. When she asked him about the other religions, the old man laughed and said that he had had enough trouble because of the three.”

I cannot but feel that such an inside view was a nice addition to what is written on the Bektashis on books and websites I have had access to. I wonder whether what the old sheikh (or baba?) had told her could perhaps give some new nuances to the interpretation of Jacob Frank as a radical antinomian preaching “redemption through sin,” as expounded by Gershom Scholem.[6] Certainly, both Jacob Frank and radical Bektashis like the old sheikh were terrible sinners from the point of view of orthodox Judaism or Islam. But their aim was not to be good Muslims or Jews, but to attain the Ultimate, the Divine, the “naked” Truth. And in their view, any orthodoxy, any religion, was or could become an obstacle on the way to attaining it. Thus, it had to be cast away, like the shell of an oyster or a nut.

We could perhaps even ask whether Frank didn’t follow in all seriousness the precept of Deuteronomy that every practicing Jew repeats in his Shema prayer: “You must love God your Lord with all your heart, all your soul, and all your might.” If you love God in this way, you can’t love your religion with the same fervor. The teaching of the “anti-Talmudist” Frank could have given birth to a different type of Talmud, if his movement had survived longer and gained some recognition outside the rather limited circle of his followers.

It is interesting that Frank too spoke of shells, probably inspired by the Zoharist tradition: “This help [given by God to save his kingdom] is like a walnut from which we take away the green shell; then, the nut itself is seen, but it is still covered with a hard shell that has to be broken in order to get to the core inside it.”[7]

There is no essential difference between the sayings of the Bektashi sheikh and Jacob Frank’s. This means that they share a common mystical tradition. It has probably been better preserved in the Near East, which up to the present day is an ethnic and religious mosaic where different communities interact both in antagonistic and friendly ways. Both the Sabbatean-Frankist movements and some Sufi orders have certainly had more similarities than is often acknowledged. This means that in order to understand the genesis and development of these movements we must not study them in isolation but in their mutual interaction. I don’t think that we should try to explain cultural, even linguistic, phenomena primarily in their own context, avoiding or even ignoring the influences of other cultures, languages, or religions. Here, I think Moshe Idel is right when he writes that “there is indeed no categorical difference between the manner in which Jewish and other mystical symbolisms have emerged.”[8]

One of the basic ideas we find in Frank’s sermons is his devotion to the Shekhinah, which he calls “the Maiden” (Panna) and at least partly identifies with the Holy Virgin of the Catholic tradition. Here it is perhaps reasonable to keep in mind the fact that among the Bektashis, women are considered equal to men and take part in all important rituals. The person to whom the old sheikh told his unorthodox views was a girl…

Most authors take for granted that Frank was a libertine, a kind of precursor of the hippy-era sexual revolution. But his acts can be interpreted somewhat differently. Reading the chronicle of his deeds and sayings we can conclude that he and his disciples certainly practiced ritual sex.[9] Here we find a description of the ritual of “extinguishing the candles,” something the Turkish heterodox religious groups are, justly or unjustly, accused of practicing. But ritual sex is not free sex. When Frank chose a man and a woman whom he ordered to fornicate, most often he did not ask them about their own wishes or sympathies.

The chronicle mentions several times that Frank used to send some men from his entourage (including my ancestor Jakub Kapliński, brother of Hannah Frank) to Istanbul. Jan Doktór sees this as a sign of Frank’s continuing ties with some heterodox Muslim groups, citing one of his sayings about his future reconversion to the “mahometan faith.”[10]

Jacob Frank lived between two eras. Like most important leaders of mass movements before him, he was a mystic, a visionary; his talks are sermons. But at the same time, he used religion in a pragmatic way, helped by his probable understanding of the three religions having the same inner core, the real “nut” inside several shells. This relativistic attitude gave him a free hand to use any of them as means to achieve his aims. And one, perhaps the foremost, of these aims was to establish a state for his people, a Jewish state. This he attempted to achieve with the help of conversion and negotiations with rulers and religious leaders in Turkey, Austria, and Russia. Still, in his time it was possible only if the Jews converted to a state religion, be it Islam, Catholicism, or Orthodoxy. And in his own strange way, he achieved something. Frank’s estate in Offenbach was an ephemeral micro-state, but still the first Jewish state in the modern world, Frank being its sovereign ruler, although the extent of his sovereignty is still not fully clear. As a ruler, he was both an eccentric and a realist. As a realist he understood the necessity of giving “his Jews” military training, and some of the Frankists later became military men. But his eccentricity, his waste of money on luxury and pomp, undermined the finances of his state, leading it quickly to bankruptcy. It would be unjust to write off Frank’s achievements completely. Still, I think we can call him a precursor of the Zionists, most of whom were also not Orthodox Jews anymore, having gone further in their emancipation, a process certainly influenced by the Frankist heresy.

It would also be unjust to Frank to deny that some of his sermons are quite interesting and impressive, even to modern readers. As his story is intimately connected with my family story, I cannot read without being moved the account of a ceremony that took place roughly a year before his death, when he was already seriously ill. We can perhaps call it baptism, and the child “baptized” by Frank was my ancestor Eliasz Adam Kapliński.

When the Lord was dressing the first child of the Turk, who was the middle Kaplinski, he made with him the following ceremony: He himself took water in his h[oly] hand and after having washed his head he put the turban on it and after having put around his neck a silk scarf he began to weep so bitterly that tears streamed down his holy face. Afterwards the Lord said to [the wife of] Kaplinski, who was present, ‘There will be three ships on which True believers will be: The first ship, on which I too will be, will be most fortunate and they will always be together with me; the second ship will be near me, will be also greatly fortunate and [people there] will also be able to see me; but the third will be very far away. May God grant that [people there] might see my face once in three years, but perhaps never at all. Those words the Lord ordered all those here at the gathering to annunciate to the Company.’[11]

I don’t know and nobody really knows what exactly Frank meant by talking of the ships. But his vision is quite poetical and poetry keeps some of its lure even when it’s not really understood. Like the poetry in sacred books.

Notes:

[1] Jan Doktór, Rozmaite adnotacje, przypadki, czynności i anekdoty pańskie, opracował, przygotował do druku i opatrzył wstępem (Warszawa: Tikkun, 1996), 107.

[2] Historya Franka i Frankistów, napisał Zygmunt Lucyan Sulima, (Kraków: 1893).

[3] Abraham G. Duker, “Polish Frankism’s Duration: From Cabbalistic Judaism to Roman Catholicism and from Jewishness to Polishness,” Jewish Social Studies 25 no. 4 (1963): 289.

[4] Alexander Kraushar, Jacob Frank: The End to the Sabbataian Heresy , (Lanham: University Press of America, 2001).

[5] Jan Doktór, ed. Księga słów pańskich, ezoteryczne wykłady Jakuba Franka, vol 1-2 (Warszawa: Semper, 1997).

[6] Gershom Scholem, “Redemption through Sin,” in The Messianic Idea in Judaism and Other Essays on Jewish Spirituality (New York: Schocken Books, 1971), 78-141.

[7] Jan Doktór, Księga słów Pańskich, ezozteryczne wykłady Jakuba Franka, opracowanie naukowe i komentarze , (Warszawa: Semper, 1997), 2:15.

[8] Moshe Idel, Messianic Mystics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 270.

[9] Jan Doktór, Rozmaite adnotacje, przypadki, czynności i anekdoty pańskie, opracował, przygotował do druku i opatrzył wstępem (Warszawa: Tikkun, 1996), 60-61.

[10] Rozmaite adnotacje, p. 101 and 109.

[11] Jan Doktór, Rozmaite adnotacje, 92. Also see Kraushar, 337. There is also a translation of this document by Harris Lenowitz that I used in part: http://www.scribd.com/doc/58894013/Jacob-Frank-The-Master-s-Words. Unfortunately, there are many mistakes in this translation that I had to correct.

Leave a Reply