Ezidi Poetry (2014)

Historical Context: Ezidi Poetry (2014)

This poem is a part of a collection of poems which was published in Vol 5.1 of JLS.

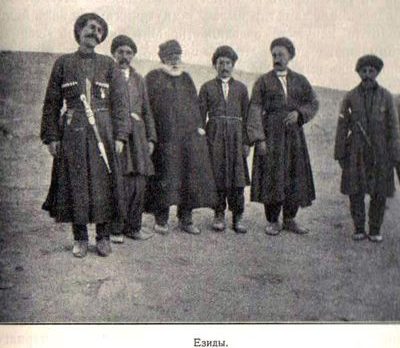

August 2014 was probably the most difficult and blood-soaked month in the recent history of the Ezidi community in Northern Iraq. The Ezidis are an ancient Kurdish- speaking ethno-religious group, whose believers are considered by Islamists to be “devil worshippers” and thus “the worst of infidels.” On August 3, 2014, Islamic State (IS) militants invaded the Shingal (Kurdish for Sinjar) region—an area that was populated at that time largely by Ezidis—with a clear and preannounced mission: to eliminate the Ezidi presence there.

This new wave of Ezidi “posttraumatic poetry” provides an invaluable glimpse into the depths of the community’s traumatic collective memory—of events of the last year and of the long line of persecutions against them.

Read more analysis here

“I Own Nothing Save My Dreams”: Ezidis Recount Their Tragedy

Idan Barir

August 2014 was probably the most difficult and blood-soaked month in the recent history of the Ezidi (Yezidi) community in Northern Iraq. The Ezidis are an ancient Kurdish-speaking ethno-religious group, whose believers are considered by Islamists to be “devil worshippers” and thus “the worst of infidels.” On August 3, 2014, Islamic State (IS) militants invaded the Shingal (Kurdish for Sinjar) region—an area that was populated at that time largely by Ezidis—with a clear and preannounced mission: to eliminate the Ezidi presence there. The Kurdish Peshmerga forces, the only military force that had pledged to grant the persecuted and threatened Ezidi minority protection, surprisingly withdrew from the battlefield in the entire Shingal region, leaving some 350,000 Ezidis at the mercy of their worst of enemies. Approximately 80,000 Ezidi men, women, children, and the elderly—who could not flee by car to Iraqi Kurdistan—had to find refuge among the peaks and ravines of Mount Shingal in the scorching heat of the Iraqi desert. Hundreds of Ezidis, mostly children, the sick, and the disabled, lost their lives to famine, thirst, and disease during the weeks spent on the mountain. Ultimately, the stranded Ezidis were rescued by Kurdish forces from Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan) and were transported through Syrian territory to Iraqi Kurdistan. On August 6, only three days after the Shingal atrocities took place, IS forces invaded the Ezidi villages of Baʿshiqa and Bahzani, some sixteen kilometers (ten miles) east of IS-controlled Mosul. They took advantage of both the Peshmerga’s retreat and the horror that befell the town’s residents after seeing what had happened in Shingal, quickly occupying the towns and driving their entire Ezidi population, estimated at 30,000, into Iraqi Kurdistan.

- + Historical Context

-

Historical Context: Ezidi Poetry (2014)

This poem is a part of a collection of poems which was published in Vol 5.1 of JLS.

August 2014 was probably the most difficult and blood-soaked month in the recent history of the Ezidi community in Northern Iraq. The Ezidis are an ancient Kurdish- speaking ethno-religious group, whose believers are considered by Islamists to be “devil worshippers” and thus “the worst of infidels.” On August 3, 2014, Islamic State (IS) militants invaded the Shingal (Kurdish for Sinjar) region—an area that was populated at that time largely by Ezidis—with a clear and preannounced mission: to eliminate the Ezidi presence there.

This new wave of Ezidi “posttraumatic poetry” provides an invaluable glimpse into the depths of the community’s traumatic collective memory—of events of the last year and of the long line of persecutions against them.

Read more analysis here

- + Analysis

-

“I Own Nothing Save My Dreams”: Ezidis Recount Their Tragedy

Idan Barir

August 2014 was probably the most difficult and blood-soaked month in the recent history of the Ezidi (Yezidi) community in Northern Iraq. The Ezidis are an ancient Kurdish-speaking ethno-religious group, whose believers are considered by Islamists to be “devil worshippers” and thus “the worst of infidels.” On August 3, 2014, Islamic State (IS) militants invaded the Shingal (Kurdish for Sinjar) region—an area that was populated at that time largely by Ezidis—with a clear and preannounced mission: to eliminate the Ezidi presence there. The Kurdish Peshmerga forces, the only military force that had pledged to grant the persecuted and threatened Ezidi minority protection, surprisingly withdrew from the battlefield in the entire Shingal region, leaving some 350,000 Ezidis at the mercy of their worst of enemies. Approximately 80,000 Ezidi men, women, children, and the elderly—who could not flee by car to Iraqi Kurdistan—had to find refuge among the peaks and ravines of Mount Shingal in the scorching heat of the Iraqi desert. Hundreds of Ezidis, mostly children, the sick, and the disabled, lost their lives to famine, thirst, and disease during the weeks spent on the mountain. Ultimately, the stranded Ezidis were rescued by Kurdish forces from Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan) and were transported through Syrian territory to Iraqi Kurdistan. On August 6, only three days after the Shingal atrocities took place, IS forces invaded the Ezidi villages of Baʿshiqa and Bahzani, some sixteen kilometers (ten miles) east of IS-controlled Mosul. They took advantage of both the Peshmerga’s retreat and the horror that befell the town’s residents after seeing what had happened in Shingal, quickly occupying the towns and driving their entire Ezidi population, estimated at 30,000, into Iraqi Kurdistan.

Ezidi I Am

Haji Mershawi

I bear the pain of 74 genocides

and a million years of sobbing.

My distinguishing marks are

a shut mouth and a paralyzed will.

The Creator does not know me

and no road map can contain me.

The Most Merciful’s angels abhor me.

No indulgence will speak in my favor

and no Qur’anic verses will fortify my walls.

I am the other’s paved way to paradise.

I apologize to everyone who killed me

if he did not make it to heaven.

If he did make it, I expect no gratitude.

Agony is inherent in my genes.

Pain roots itself in my blood stream.

Gloom clothes itself in my body cells.

I am destined to live

only as the other pleases;

I am destined to die

only when the other pleases—

crucified on the ruins of God’s memory,

outcast from the living side of life,

thrown like an agonizing lariat

on the serrated blade of oblivion.

My only homeland exists in the sheen of tears.

My only condolence exists in the conch of grief.

In me, imprisoned, the flood of my humanity abscesses,

pours out like pus.

No mediation will ever get me closer

to that forgotten God

and no escape for me

from his ill-tempered wills.

Bound I am in the frost of fears,

kneaded I am in the dough of disappointments

mingled in weeping, mixed with bitterness—

my voice a mere stifled groan

in a forest of lamentations.

Hay blocks the ears of the universe

while the Lord troubles himself with other options.

(Untitled)

Sarmad Al-Aldakhi

This city stands upright

just like an Iraqi palm,

but it does not rise up.

It may tumble down to hug the child

who sells handkerchiefs on the roads—

this boy, who brought his heart to pain,

his eyes to tears, his naked body

to the street with no end, his weeping

voice to ears that will not listen.

Nothing here resembles Shingal!

No poets walking the streets;

the poems smell of gunpowder.

My baby girl falls in the lap of crying,

and even my sweetheart

satisfies herself with stealing my shirt.

She prefers me staying with her

only at the end of the night.

Nothing here resembles Shingal![1]

The bread’s smell at dawn,

Murad’s Rose Petals[2],

Khidhir Faqeer’s poems,[3]

the anemones’ crimson,

the qewwalin‘s[4] roar

at the morning’s feast.

Nothing here resembles Shingal!

Notes:

[1] Shingal is the common name in Kurdish for Sinjar, a mountain ridge located some 120km (75 miles) west of Mosul, in northern Iraq. Shingal is also the name of a big town on the southern slopes of the mountain. Here, it seems that the poet is referring to the entire region around the ridge, inhabited mostly by Ezidis and also known as Shingal or Sinjar

[2] The poem alludes to the Yazidi poet Murad Suleiman Allo and his collection of poetry “Rose Petals” (Bitalāt Al-Ward)

[3] The late Khidhir Faqeer was a popular poet from Shingal known as a singer of local folk songs in the region.

[4] Qewwalin [pl.] are Ezidis from a certain religious group responsible for playing Daff and Shabbāba (kinds of drum and flute, respectively), accompanying Ezidi religious ceremonies.

Identity

Haiman Alkarsafy

Tell them that I will not die,

even if they break the cane

that leads me toward history.

My body will find the strength

to conquer obstinacy.

It will gather its extremities,

and, over the shards of this child’s dream,

I shall return to my home.

Tell them that, like rats, they fought me,

or butchered me,

with my identity caught between their jaws.

This mountain hugged the neighbor’s son.

Tell them

that these are not mere whispers,

nor are they fake patriotic cries—but

my personal identity,

my Ezidi self,

my language,

my Shingali self—

and I shall not be confused.

I am still alive

in the bodies of the children.

I shall remain until eternity,

holding banners of peace and victory in my hands.

Rain Rain

Sana Tapany

They asked the sky, source of compassion:

Do you know on whom you pour your raindrops?The sky answered most arrogantly:

On the seeds, the earth, and the mountain.

I water them for the spring to be more beautiful,

for people to be happier, for us to live

with more hope in our lives.They replied with great shame:

How, then, have you not heard of the children of Sinjar?

They have neither roof over their heads,

nor sock nor sandal on their feet.

Have you not heard of the women of Sinjar?

Despite the tragedy they experienced,

their homes became no more than tents

of unprotected cloth. Nor have you heard

of the men of Sinjar? Those who survived death

fight to rescue guiltless abducted captives.

Have mercy on them, our dear sky.

So if this earth shows no mercy for them,

You, sky, will be more merciful to them.

The Captive

Murad Suleiman Allo

Join the caravan of love and go past my caravans,

insert a letter to the verse of the Nawafel prayer.[1]

Shout out loud in the face of blackening death,

the soft chirping of nightingales will not suffice today.

Which prayer would you prefer, hazel eyes of mine?

Reiterate Shingal’s[2] laments, do not ask questions.

Always put your trust in Tawûsê Melek,[3] head of the angels,

in his name, in his power I will shatter your shackles and chains.

Let the Daeshie[4] ask Angel Gabriel about his fidelity.

Since when was the caliphate given to wicked idlers?

If you spill our blood, it will not dry out.

Since when did the desert run out of sand?

You will not succeed in destroying us or finish us with your fermans.[5]

You have not nor will you succeed in incinerating the civilization of Babylon.

There is no glory in setting a neighbor against another,

and no reward in the capturing of pregnant women.

You may say that your invasion is a justified act,

as the thorns throng together along the stem.

You ignorant fool, your heart black as your uniform.

You worthless whoreson of the desert, master of filth.

Ask the wars of Iraq about our endless capacities,

the Kalashnikov, and the blasts of mortars and shells.

We have always been spearheads in the field of battle,

we paid in martyrs from our ranks and in widows’ tears.

We shall squeeze the Daeshies and chop off their tails,

and as furnaces blaze we will only voice howls of joy.

This is the nature of the Ezidi, honest and vigorous,

he never consented to become a passive subject.

We will restore the glory of Dawûd, Mirza, and Basha,[6]

and of those defending fiercely the love of the stem for the sickle.

Behold how Kheiry pursued their pathand how every fighter walks this path today.

Notes:

[1] In Islam – Supererogatory prayer, optional prayers outside the obligatory daily prayer, acquitting extra benefits on the believer and demonstrating his piety.

[2] Shingal is the Kurdish name of Sinjar.

[3] Tawûsê Melek, or ‘the Peacock Angel’ is the head of the angels according to the Ezidi belief, and is sometimes identified as Angel Gabriel.

[4] Common name among Ezidis (and others) for ISIS fighters.

[5] Originally – Firmanat. This word was originally borrowed from Ottoman Turkish, in which it means a Sultanic decree. Ezidis often use this word to refer to the annihilation campaigns that were carried out against the Ezidi community for its religious difference from Sunni Islam, many of which occurred during the Ottoman period, under a Sultanic decree ordering the killing and/or the forced conversion of ‘infidel’ Ezidis.

[6] Dawûd is short for Dawûde Dawûd, leader of the Ezidi tribe of Mihrikan in Shingal during the 1920s and 1930s. He is remembered as commander of a large Ezidi rebellion against the British authorities in Shingal that began in 1925. Mirza is short for Mir Ezidi Mirza Dasani, mythical ruler of the Ezidis in the 17th century, who became known as a hero in the battlefield. Mirza is remembered as the Ezidi leader who improved the ties between Ezidis and the Ottoman authorities to the degree that he was appointed governor of the entire province of Mosul in 1649. Basha was the nickname of Hamo Shiro, a prominent leader of the Ezidi Faqiran tribe from Shingal. Hamo Shiro rose to prominence when he led his tribe in battle against one of the great annihilation campaigns waged by the Ottoman Empire against the Ezidis of Shingal in 1892 and succeeded in driving the Ottoman forces away from the area. Following Shiro’s granting asylum in Shingal to Armenian refugees fleeing the genocide in Anatolia during WWI, the British authorities appointed him governor of Shingal and its Ezidi communities, and granted him the title of Pasha (Basha in Arabic).

- + Ezidi I Am/ Haji Mershawi

-

Ezidi I Am

Haji Mershawi

I bear the pain of 74 genocides

and a million years of sobbing.

My distinguishing marks are

a shut mouth and a paralyzed will.

The Creator does not know me

and no road map can contain me.

The Most Merciful’s angels abhor me.

No indulgence will speak in my favor

and no Qur’anic verses will fortify my walls.

I am the other’s paved way to paradise.

I apologize to everyone who killed me

if he did not make it to heaven.

If he did make it, I expect no gratitude.

Agony is inherent in my genes.

Pain roots itself in my blood stream.

Gloom clothes itself in my body cells.

I am destined to live

only as the other pleases;

I am destined to die

only when the other pleases—

crucified on the ruins of God’s memory,

outcast from the living side of life,

thrown like an agonizing lariat

on the serrated blade of oblivion.

My only homeland exists in the sheen of tears.

My only condolence exists in the conch of grief.

In me, imprisoned, the flood of my humanity abscesses,

pours out like pus.

No mediation will ever get me closer

to that forgotten God

and no escape for me

from his ill-tempered wills.

Bound I am in the frost of fears,

kneaded I am in the dough of disappointments

mingled in weeping, mixed with bitterness—

my voice a mere stifled groan

in a forest of lamentations.

Hay blocks the ears of the universe

while the Lord troubles himself with other options.

- + (Untitled)/ Sarmad Saleem

-

(Untitled)

Sarmad Al-Aldakhi

This city stands upright

just like an Iraqi palm,

but it does not rise up.

It may tumble down to hug the child

who sells handkerchiefs on the roads—

this boy, who brought his heart to pain,

his eyes to tears, his naked body

to the street with no end, his weeping

voice to ears that will not listen.

Nothing here resembles Shingal!

No poets walking the streets;

the poems smell of gunpowder.

My baby girl falls in the lap of crying,

and even my sweetheart

satisfies herself with stealing my shirt.

She prefers me staying with her

only at the end of the night.

Nothing here resembles Shingal![1]

The bread’s smell at dawn,

Murad’s Rose Petals[2],

Khidhir Faqeer’s poems,[3]

the anemones’ crimson,

the qewwalin‘s[4] roar

at the morning’s feast.

Nothing here resembles Shingal!

Notes:

[1] Shingal is the common name in Kurdish for Sinjar, a mountain ridge located some 120km (75 miles) west of Mosul, in northern Iraq. Shingal is also the name of a big town on the southern slopes of the mountain. Here, it seems that the poet is referring to the entire region around the ridge, inhabited mostly by Ezidis and also known as Shingal or Sinjar

[2] The poem alludes to the Yazidi poet Murad Suleiman Allo and his collection of poetry “Rose Petals” (Bitalāt Al-Ward)

[3] The late Khidhir Faqeer was a popular poet from Shingal known as a singer of local folk songs in the region.

[4] Qewwalin [pl.] are Ezidis from a certain religious group responsible for playing Daff and Shabbāba (kinds of drum and flute, respectively), accompanying Ezidi religious ceremonies.

- + Identity/ Haiman Alkarsafy

-

Identity

Haiman Alkarsafy

Tell them that I will not die,

even if they break the cane

that leads me toward history.

My body will find the strength

to conquer obstinacy.

It will gather its extremities,

and, over the shards of this child’s dream,

I shall return to my home.

Tell them that, like rats, they fought me,

or butchered me,

with my identity caught between their jaws.

This mountain hugged the neighbor’s son.

Tell them

that these are not mere whispers,

nor are they fake patriotic cries—but

my personal identity,

my Ezidi self,

my language,

my Shingali self—

and I shall not be confused.

I am still alive

in the bodies of the children.

I shall remain until eternity,

holding banners of peace and victory in my hands.

- + Rain Rain/ Sana Tapany

-

Rain Rain

Sana Tapany

They asked the sky, source of compassion:

Do you know on whom you pour your raindrops?The sky answered most arrogantly:

On the seeds, the earth, and the mountain.

I water them for the spring to be more beautiful,

for people to be happier, for us to live

with more hope in our lives.They replied with great shame:

How, then, have you not heard of the children of Sinjar?

They have neither roof over their heads,

nor sock nor sandal on their feet.

Have you not heard of the women of Sinjar?

Despite the tragedy they experienced,

their homes became no more than tents

of unprotected cloth. Nor have you heard

of the men of Sinjar? Those who survived death

fight to rescue guiltless abducted captives.

Have mercy on them, our dear sky.

So if this earth shows no mercy for them,

You, sky, will be more merciful to them. - + The Captive/ Murad Suleiman Allo

-

The Captive

Murad Suleiman Allo

Join the caravan of love and go past my caravans,

insert a letter to the verse of the Nawafel prayer.[1]

Shout out loud in the face of blackening death,

the soft chirping of nightingales will not suffice today.

Which prayer would you prefer, hazel eyes of mine?

Reiterate Shingal’s[2] laments, do not ask questions.

Always put your trust in Tawûsê Melek,[3] head of the angels,

in his name, in his power I will shatter your shackles and chains.

Let the Daeshie[4] ask Angel Gabriel about his fidelity.

Since when was the caliphate given to wicked idlers?

If you spill our blood, it will not dry out.

Since when did the desert run out of sand?

You will not succeed in destroying us or finish us with your fermans.[5]

You have not nor will you succeed in incinerating the civilization of Babylon.

There is no glory in setting a neighbor against another,

and no reward in the capturing of pregnant women.

You may say that your invasion is a justified act,

as the thorns throng together along the stem.

You ignorant fool, your heart black as your uniform.

You worthless whoreson of the desert, master of filth.

Ask the wars of Iraq about our endless capacities,

the Kalashnikov, and the blasts of mortars and shells.

We have always been spearheads in the field of battle,

we paid in martyrs from our ranks and in widows’ tears.

We shall squeeze the Daeshies and chop off their tails,

and as furnaces blaze we will only voice howls of joy.

This is the nature of the Ezidi, honest and vigorous,

he never consented to become a passive subject.

We will restore the glory of Dawûd, Mirza, and Basha,[6]

and of those defending fiercely the love of the stem for the sickle.

Behold how Kheiry pursued their pathand how every fighter walks this path today.

Notes:

[1] In Islam – Supererogatory prayer, optional prayers outside the obligatory daily prayer, acquitting extra benefits on the believer and demonstrating his piety.

[2] Shingal is the Kurdish name of Sinjar.

[3] Tawûsê Melek, or ‘the Peacock Angel’ is the head of the angels according to the Ezidi belief, and is sometimes identified as Angel Gabriel.

[4] Common name among Ezidis (and others) for ISIS fighters.

[5] Originally – Firmanat. This word was originally borrowed from Ottoman Turkish, in which it means a Sultanic decree. Ezidis often use this word to refer to the annihilation campaigns that were carried out against the Ezidi community for its religious difference from Sunni Islam, many of which occurred during the Ottoman period, under a Sultanic decree ordering the killing and/or the forced conversion of ‘infidel’ Ezidis.

[6] Dawûd is short for Dawûde Dawûd, leader of the Ezidi tribe of Mihrikan in Shingal during the 1920s and 1930s. He is remembered as commander of a large Ezidi rebellion against the British authorities in Shingal that began in 1925. Mirza is short for Mir Ezidi Mirza Dasani, mythical ruler of the Ezidis in the 17th century, who became known as a hero in the battlefield. Mirza is remembered as the Ezidi leader who improved the ties between Ezidis and the Ottoman authorities to the degree that he was appointed governor of the entire province of Mosul in 1649. Basha was the nickname of Hamo Shiro, a prominent leader of the Ezidi Faqiran tribe from Shingal. Hamo Shiro rose to prominence when he led his tribe in battle against one of the great annihilation campaigns waged by the Ottoman Empire against the Ezidis of Shingal in 1892 and succeeded in driving the Ottoman forces away from the area. Following Shiro’s granting asylum in Shingal to Armenian refugees fleeing the genocide in Anatolia during WWI, the British authorities appointed him governor of Shingal and its Ezidi communities, and granted him the title of Pasha (Basha in Arabic).

Leave a Reply