-

Add to cartQuick view

Babel by Cemil Meriç (Translation)

“Babel,” the first chapter of Cemil Meriç’s Bu Ülke, is translated here to English for the first time. Meriç, a Turkish intellectual, inspired many scholars and leaders in post-Kemalist Turkey. “Babel” is a critical discussion of Kemalist intellectuals’ cultural and political outlook and the cultural reforms they instated. Meriç refuses to accept the divisions between East and West, religious and secular, and Right and Left which he sees as straitjackets imported from Christian Europe that prevent freedom of thought. At the same time, his writing integrates a philosophy inspired by the West with one that originates in the East and creates a symbiosis between them. He challenges the premises of the Turkish modernization project and the attempt to create a new generation, new state, new language and new culture. Writing in a subversive language, Meriç contends that a reformist project disconnected from its past is doomed to a lack of substance and failure.

$5.00Free!Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

Dreams and Nightmares: Reading Akram Aylisli’s Stone Dreams on the 100th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

Free!This article analyzes Stone Dreams, a novel by famous Azeri writer Akram Aylisli. Published in the Russian literary journal Druzhba narodov (Fraternity of peoples) in December 2012, it condemned anti-Armenian pogroms that took place in the cities of Baku and Sumgait at the end of the 1980s. The book also addressed the massacre committed by Turkish troops during the genocide of the Armenian people (1915–1923), including the mass execution of the Armenian population in Aylisli’s native town of Aylis/Agulis. On Christmas day of 1919, under orders by Turkish commander Adif Bey, almost all of the village’s Armenians were killed, with the exception of a few young girls, whom Aylisli knew when he was a young man. By the late 1980s they were gray-haired women, and the narrative of Aylisli’s novel was based on the stories told by these older people in the village. The publication of Aylisli’s novel caused mass outrage in Azerbaijan because of its alleged one-sidedness. The outrage took the form of mass demonstrations in front of Aylisli’s house, as well as the public burning of his books and accusations of treason.

Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

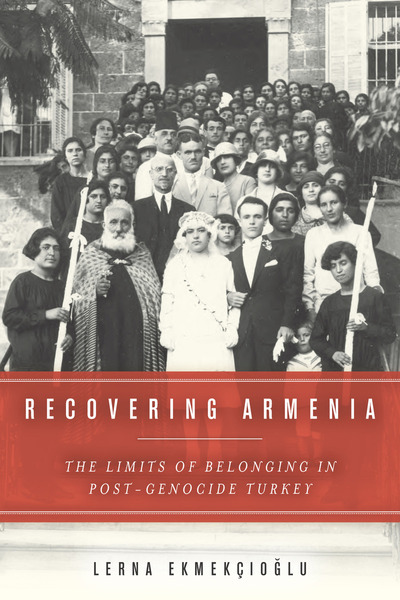

Lerna Ekmekçioğlu, Recovering Armenia: The Limits of Belonging in Post-Genocide Turkey. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016. 240 pp.

Free!Lerna Ekmekçioğlu, Recovering Armenia: The Limits of Belonging in Post-Genocide Turkey. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016. 240 pp.

Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

Review Essay: The Transforming Landscape of Turkey’s Alevi Politics

Free!Review Essay:

Elise Massicard, The Alevis in Turkey and Europe: Identity and Managing Territorial Diversity. New York: Routledge, 2013. 255 pp.Necdet Subaşı, Alevi Modernleşmesi: Sırrı Faş Eylemek. İstanbul: Timaş, 2008. 320 pp.Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

Review Essay: Tormented By Politics

Free!Umut Özkırımlı, and Spyros A. Sofos,Tormented by History: Nationalism in Greece and Turkey (London: Hurst and Co., 2008), 219 pp.

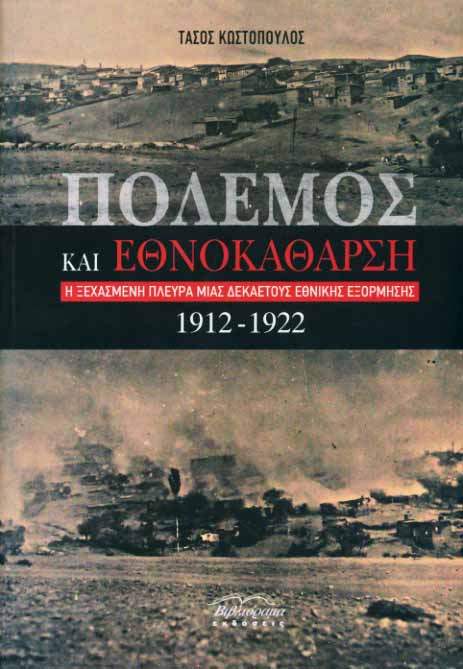

Kostopoulos, Tasos, Πόλεμος και Εθνοκάθαρση: Η Ξεχασμένη Πλευράμιας Δεκαετούς Εθνικής Εξόρμησης, 1912-1922 [War and Ethnic Cleansing: The Forgotten Side of a Ten-Year National Surge, 1912-1922] (Athens: Vilviorama, 2007), 319 pp.

Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

The Armenian Genocide in Interwar Hungarian Political Discourse

Free!This article demonstrates how the Armenian Question and the interpretations of the Armenian Genocide—both justifying and opposing it—shaped political discourse during and after the First World War in Hungary, particularly with regard to the years preceding the Holocaust. The first part briefly presents the evolution of the Armenian Question in the Hungarian public and political discourse from the late nineteenth century up to the First World War. Next the article outlines the diverse nature of Hungarian sources on the Armenian Genocide and its aftermath, corroborating that interwar Hungarian governments had detailed knowledge of the past plight and current situation of Armenians in Turkey. The third part depicts the different manifestations of the discourse on the Armenian Genocide between the two world wars in connection with refugees, anti-Semitism, and Turkish-Hungarian economic and political relations. Finally, some preliminary conclusions are drawn and some possible consequences are examined.

Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

Challenging Religious and Secularist Patriarchy: Islamist Women’s New Activism in Turkey

Free!Since the late 1990s, following the state’s process of de-politicization and exclusion, educated Islamist women in the urban centers of Turkey have been active in raising Muslim women’s identity consciousness and generating solidarity with those affected by the headscarf ban. In the women’s organizations analyzed in this article, Islamist women are carving out a niche to challenge both secularist and Islamist patriarchal practices and discourse. This article contends that organized Islamist women have become significant actors in autonomously mobilizing religious women—in the political parties and in the Islamic movement—in the democratization process. The Islamist women’s learning process has opened them up to dialogue and cooperation—on gender equality and other liberalization issues—with secular women as well as with other oppressed groups. However, their “feminist” stance creates some dilemmas for Islamist and secular women.

Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

Rethinking Turkey’s Soft Power in the Arab World: Islam, Secularism, and Democracy

Free!This article analyzes the meaning, characteristics and evolution of Turkey’s ambitions and limits in the exercising of “soft power” within the Arab World. The article’s central thesis is that Turkey’s model of “soft power” derives from a “historical evolutionary process”, in which the relationship between Islamism and republican secularism creates not two separate and conflicting worlds, but two symbiotic parts within the collective historical development that comprises contemporary Turkey. This process has enabled Turkey to develop a complex and changeable admixture of Islam, secularism and democracy; this “alchemy”, and its future developments, are the key to the meaning of Turkish “soft power”. The article will trace Turkey’s projection of soft power since the AKP’s accession to power in 2002. It will highlight both the AKP’s potential, particularly as signaled during the first mandate, and the party’s limits, which emerged in the subsequent two mandates. The article proposes that Turkey’s soft power has progressively diminished as the government’s initially fine balance between Islam, secularism and democracy has unraveled.The article is divided into four parts. The first part explores the origins of the concept of soft power in the literature and the historical process that enabled Turkey to project that power toward the Arab world. The next part depicts the peculiarities of Turkish soft power as instanced during the AKP’s first mandate. The third part describes the developments that made Turkey “attractive” to the Arab world and the relationship between the projection of Turkish soft power and the birth of the “Arab spring”. Finally, the last part considers the Arab spring’s effects on Turkish soft power. Of particular note are the limits and contradictions that have diluted Turkey’s soft power credibility.Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

The Silver Lining of the Turkey-EU Refugee Deal: Pushing Ahead with the Integration of Syrian Refugees into Turkish Society

Free!One of the repercussions of the Syrian civil war is that Turkey has become host to the largest number of refugees in the world. While initially Turkish perceptions were that the refugees would return to Syria after the end of the conflict, there is a growing recognition that at least half of them will remain in Turkey. This acknowledgment has required Turkey to rethink its policies toward its Syrian “guests.” The thorniest issues have been the question of granting work permits and citizenship to some of the refugees. The claim put forward in this article is that the attention these issues gained in 2016 can partly be explained by the Turkey-EU refugee deal, which suggests that despite the criticism against it, it has also had a positive effect in promoting the integration of Syrian refugees into Turkey.

Add to cartQuick view

- Home

- About JLS

- Issues

- Vol. 9 No. 1 | Summer 2019

- Vol 8 No 2 Winter 2018

- Vol. 8, No. 1: Summer 2018

- Vol. 7, No. 2: Winter 2017

- Vol. 7, 1: Summer 2017

- Vol. 6, Summer/Winter 2016

- Vol. 5, No. 2 Winter 2015

- Vol. 5, No. 1 Summer 2015

- Vol. 4, No. 2 Winter 2014

- Vol. 4, No. 1 Summer 2014

- Vol. 3, No. 2 Winter 2013

- Vol. 3, No. 1 Summer 2013

- Vol. 2, No. 2 Winter 2012

- Vol. 2, No. 1 Summer 2012

- Vol. 1, No. 2 Winter 2011

- Vol. 1, No. 1 Summer 2011

- Blog

- dock-uments

- Subscribe

- Submit

- Contact