Writing the Body and the Rhetoric of Protest in Arab Women’s Literature

Miral al-Tahawy was born in 1968 to a bedouin family of the al-Hanadi tribe in the Egyptian Delta. She is often recognized as the first Egyptian bedouin woman writer to publish modern Arabic literature and to provide an authentic glimpse into Egyptian bedouin life, particularly that of women. Al-Tahawy grew up in a traditional bedouin family—however, her father chose to educate his daughters. She completed a PhD in Arabic language and literature at Cairo University and immigrated to the United States in 2008.

In her work, al-Tahawy exposes the lives of bedouin women in lyrical prose. She has published four novels, all of which have been translated into English: The Tent (AUC Press, 1998), Blue Aubergine (AUC Press, 2002), Gazelle Tracks (Garnet Publishing/AUC Press, 2009), and most recently, Brooklyn Heights (AUC Press, 2012), which received the 2010 Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature and was shortlisted for the 2011 Arabic Booker Prize. Her literary work has received international acclaim and has been translated into more than fifteen languages.

Al-Tahawy has also published two academic books, as well as numerous scholarly articles. Her academic interests range from bedouin folk traditions to modern Arab women’s writing. She is currently an associate professor of modern Arabic literature at Arizona State University.

The Female Body and the Female Word in a Schizophrenic Age

Introduction by Nathalie Alyon

Miral al-Tahawy’s first novel, The Tent, is narrated by Fatima, a young bedouin girl trapped within the walls of her father’s encampment in the Egyptian desert. Her small body climbs trees to gaze past the gates that remain locked to the women of the household, travels to the bottoms of wells to create alternate realities with imaginary characters, and finds solace lying on the lap of the slave-girl, Sardoub. In Fatima’s world women cannot leave the confines of their house unless to wed men chosen for them. Paradoxically, the slave women are among the few local women having any freedom of movement, often limited to weekly trips to the market.

In The Tent, women’s lives in the desert are exposed through descriptions of the restrictions, violence, and curses directed against their bodies. Fatima’s body belongs to her only partially. She dreams of escaping her prison, “to run through the fields and pick grass like Sasa [the slave], or run across the desert like Mouha [a wandering woman].” [1] As Fatima imagines a life beyond the gates, she lives in her body, crawling from room to room, jumping from tree to tree. Yet even her body abandons her when a fall leaves her with one leg amputated. As her ability to move about decreases, she further retreats into a world of stories, folktales, and imagined realities: I looked down into my lap, burying my head in paper. I felt that the letters were creatures of the night, roaming over my body, weighing it down. What is Fatima doing with letters, with words, when the loneliness is excruciating? [2]

Indeed, all of al-Tahawy’s characters are girls or women who carry a sense of not belonging and who must deal with their loneliness as they navigate worlds defined by gender roles. [3] Her latest novel, Brooklyn Heights, explores similar themes through more complex plotlines. Brooklyn Heights unfolds in Hend’s new home in New York, which feels as alienating and distant as her home back in the Egyptian desert. Despite leaving the physical boundaries of Egypt behind, memories of a previous life in the desert continually haunt and permeate every corner of her new country.

It is possible to approach Hend as a grown-up Fatima who, in an alternate reality, manages to escape the locked gates of her desert home and make a new life in the United States. Fatima and Hend both draw power from their bodies and from words. Fatima inhabits the stories she creates; Hend carries poems she hopes to write one day, she aspires to become an accomplished writer. Like Fatima, Hend grows increasingly isolated and dislocated from the people around her, as well as from her own body.

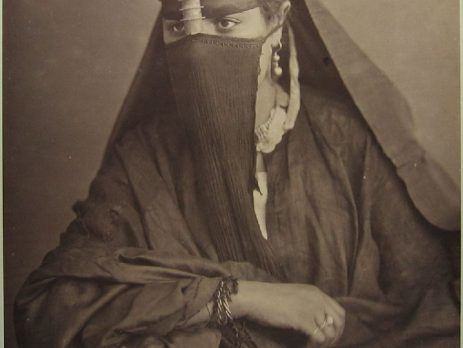

The body, its covering and uncovering, is a recurring theme in al-Tahawy’s fictional world and in her personal history. A section in Brooklyn Heights echoes al-Tahawy’s experience of shedding the hijab: “Hend was the first girl at school to put on the long, flowing hijab. . . . But in the same way that she had been the first girl to put on that long black curtain, she was the first one to discard it.”[4] Similarly, al-Tahawy left her family home “unaccompanied by a male relative for the first time when she was 26, and still had to be covered from head to foot.” Today she lives in Arizona and is a professor of Arabic language and literature. She has returned to a desert landscape, thousands of miles away from the desert where she was born. Only this time, the desert climate frees her from unnecessary covering. [5]

The symbolism of the hijab in the lives of Arab women is the main anchor in “Writing the Body and the Rhetoric of Protest in Arab Women’s Literature.” In this poignant essay, al-Tahawy draws a parallel between the female body and women’s writing as tools for protest and change, juxtaposing it with the long history of the female body having been made an object of oppression, violence, shame, and guilt. She invites a host of questions for further deliberation: Can free writing happen under the hijab? Could the choice to wear the hijab be a symbol of freedom, as is the choice to remove it? To whom does the female body that has been transformed from an object of oppression to a tool for protest belong?

Al-Tahawy argues that the act of revealing the body—whether through the removal of clothes or through writing—is inherently an expression of power and protest rather than “a kind of seduction,” as the patriarchal critical reception ascribes to women’s writing. Al-Tahawy’s essay exposes the mechanisms behind this silent illness that plagues women who cannot freely write about their bodies and identifies the fear-induced self-censorship kindled by the conservative tendency to reduce women’s writing to feminine mystique.

The stifling power of self-censorship in suppressing a writer’s creativity was perhaps best expressed by George Orwell: “To write in plain, vigorous language one has to think fearlessly, and if one thinks fearlessly one cannot be politically orthodox.” It is all but impossible for a prose writer to sustain “inventiveness” in an environment where she must consider the sociopolitical consequences of her words. [6] For women’s writing, a denial of the female body is to write in the “age of schizophrenia” that Orwell attributes to the intellectuals of the post–Second World War era.

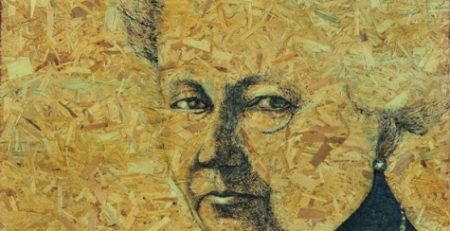

Arab women writers and artists are not the only ones to have been victims of the self-censorship resulting from patriarchal criticism that categorizes women’s writing as sensual, spiritual, or feminine. American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, who also had a close relationship with the desert, comes to mind. To the detriment of the wide array of themes O’Keeffe expressed throughout her eighty-year career, critics often reduced her paintings to a single question: Are O’Keeffe’s flowers vaginas? [7] Despite her consistent denial that her paintings represented the erotic, O’Keeffe’s work continues to be viewed as representing female sexuality—an interpretation that posits her as essentially a “female” artist and her paintings as having “feminine” qualities.

O’Keeffe’s flowers are not vaginas, because she said they are not. Decades later, al-Tahawy makes the case for women artists who want to make their flowers into vaginas to be able to do so without being cast aside as erotic, vulgar, or simply feminine. She calls for the expression of the female body in its full complexity to transcend patriarchal norms that box in the feminine. Her work presents a pioneering voice in this struggle to empower the female body, as well as the female word.

Notes

1 Miral al-Tahawy, The Tent (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2010), Kindle edition, chap. 1.

2 Ibid., chap. 11.

3 Ariel M. Sheetrit, “Deterritorialization of Belonging: Between Home and the Unhomely in Miral

al-Tahawy’s Brooklyn Heights and Salman Natur’s She, the Autumn, and Me,” Journal of Levantine Studies 3, no. 2 (2013): 72.

4 Miral al-Tahawy, Brooklyn Heights, trans. Sameh Salim (London: Faber and Faber, 2012), 66, 68.

5 Aaron Bady, “Interview: Miral al-Tahawy,” Post45, November 8, 2014, accessed April 22, 2017,

http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/11/interview-miral-al-tahawy/.

6 George Orwell, “The Prevention of Literature,” in Books v. Cigarettes (London: Penguin Books, 2008), 33.

7 Hannah Ellis-Petersen, “Flowers or Vaginas? Georgia O’Keeffe Tate Show to Challenge Sexual Clichés,” The Guardian, March 1, 2016, accessed April 22, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/ artanddesign/2016/mar/01/georgia-okeeffe-show-at-tate-modern-to-challenge-outdated-viewsof-artist.

- + About the Author

-

Miral al-Tahawy was born in 1968 to a bedouin family of the al-Hanadi tribe in the Egyptian Delta. She is often recognized as the first Egyptian bedouin woman writer to publish modern Arabic literature and to provide an authentic glimpse into Egyptian bedouin life, particularly that of women. Al-Tahawy grew up in a traditional bedouin family—however, her father chose to educate his daughters. She completed a PhD in Arabic language and literature at Cairo University and immigrated to the United States in 2008.

In her work, al-Tahawy exposes the lives of bedouin women in lyrical prose. She has published four novels, all of which have been translated into English: The Tent (AUC Press, 1998), Blue Aubergine (AUC Press, 2002), Gazelle Tracks (Garnet Publishing/AUC Press, 2009), and most recently, Brooklyn Heights (AUC Press, 2012), which received the 2010 Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature and was shortlisted for the 2011 Arabic Booker Prize. Her literary work has received international acclaim and has been translated into more than fifteen languages.

Al-Tahawy has also published two academic books, as well as numerous scholarly articles. Her academic interests range from bedouin folk traditions to modern Arab women’s writing. She is currently an associate professor of modern Arabic literature at Arizona State University.

- + Analysis

-

The Female Body and the Female Word in a Schizophrenic Age

Introduction by Nathalie Alyon

Miral al-Tahawy’s first novel, The Tent, is narrated by Fatima, a young bedouin girl trapped within the walls of her father’s encampment in the Egyptian desert. Her small body climbs trees to gaze past the gates that remain locked to the women of the household, travels to the bottoms of wells to create alternate realities with imaginary characters, and finds solace lying on the lap of the slave-girl, Sardoub. In Fatima’s world women cannot leave the confines of their house unless to wed men chosen for them. Paradoxically, the slave women are among the few local women having any freedom of movement, often limited to weekly trips to the market.

In The Tent, women’s lives in the desert are exposed through descriptions of the restrictions, violence, and curses directed against their bodies. Fatima’s body belongs to her only partially. She dreams of escaping her prison, “to run through the fields and pick grass like Sasa [the slave], or run across the desert like Mouha [a wandering woman].” [1] As Fatima imagines a life beyond the gates, she lives in her body, crawling from room to room, jumping from tree to tree. Yet even her body abandons her when a fall leaves her with one leg amputated. As her ability to move about decreases, she further retreats into a world of stories, folktales, and imagined realities: I looked down into my lap, burying my head in paper. I felt that the letters were creatures of the night, roaming over my body, weighing it down. What is Fatima doing with letters, with words, when the loneliness is excruciating? [2]

Indeed, all of al-Tahawy’s characters are girls or women who carry a sense of not belonging and who must deal with their loneliness as they navigate worlds defined by gender roles. [3] Her latest novel, Brooklyn Heights, explores similar themes through more complex plotlines. Brooklyn Heights unfolds in Hend’s new home in New York, which feels as alienating and distant as her home back in the Egyptian desert. Despite leaving the physical boundaries of Egypt behind, memories of a previous life in the desert continually haunt and permeate every corner of her new country.

It is possible to approach Hend as a grown-up Fatima who, in an alternate reality, manages to escape the locked gates of her desert home and make a new life in the United States. Fatima and Hend both draw power from their bodies and from words. Fatima inhabits the stories she creates; Hend carries poems she hopes to write one day, she aspires to become an accomplished writer. Like Fatima, Hend grows increasingly isolated and dislocated from the people around her, as well as from her own body.

The body, its covering and uncovering, is a recurring theme in al-Tahawy’s fictional world and in her personal history. A section in Brooklyn Heights echoes al-Tahawy’s experience of shedding the hijab: “Hend was the first girl at school to put on the long, flowing hijab. . . . But in the same way that she had been the first girl to put on that long black curtain, she was the first one to discard it.”[4] Similarly, al-Tahawy left her family home “unaccompanied by a male relative for the first time when she was 26, and still had to be covered from head to foot.” Today she lives in Arizona and is a professor of Arabic language and literature. She has returned to a desert landscape, thousands of miles away from the desert where she was born. Only this time, the desert climate frees her from unnecessary covering. [5]

The symbolism of the hijab in the lives of Arab women is the main anchor in “Writing the Body and the Rhetoric of Protest in Arab Women’s Literature.” In this poignant essay, al-Tahawy draws a parallel between the female body and women’s writing as tools for protest and change, juxtaposing it with the long history of the female body having been made an object of oppression, violence, shame, and guilt. She invites a host of questions for further deliberation: Can free writing happen under the hijab? Could the choice to wear the hijab be a symbol of freedom, as is the choice to remove it? To whom does the female body that has been transformed from an object of oppression to a tool for protest belong?

Al-Tahawy argues that the act of revealing the body—whether through the removal of clothes or through writing—is inherently an expression of power and protest rather than “a kind of seduction,” as the patriarchal critical reception ascribes to women’s writing. Al-Tahawy’s essay exposes the mechanisms behind this silent illness that plagues women who cannot freely write about their bodies and identifies the fear-induced self-censorship kindled by the conservative tendency to reduce women’s writing to feminine mystique.

The stifling power of self-censorship in suppressing a writer’s creativity was perhaps best expressed by George Orwell: “To write in plain, vigorous language one has to think fearlessly, and if one thinks fearlessly one cannot be politically orthodox.” It is all but impossible for a prose writer to sustain “inventiveness” in an environment where she must consider the sociopolitical consequences of her words. [6] For women’s writing, a denial of the female body is to write in the “age of schizophrenia” that Orwell attributes to the intellectuals of the post–Second World War era.

Arab women writers and artists are not the only ones to have been victims of the self-censorship resulting from patriarchal criticism that categorizes women’s writing as sensual, spiritual, or feminine. American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, who also had a close relationship with the desert, comes to mind. To the detriment of the wide array of themes O’Keeffe expressed throughout her eighty-year career, critics often reduced her paintings to a single question: Are O’Keeffe’s flowers vaginas? [7] Despite her consistent denial that her paintings represented the erotic, O’Keeffe’s work continues to be viewed as representing female sexuality—an interpretation that posits her as essentially a “female” artist and her paintings as having “feminine” qualities.

O’Keeffe’s flowers are not vaginas, because she said they are not. Decades later, al-Tahawy makes the case for women artists who want to make their flowers into vaginas to be able to do so without being cast aside as erotic, vulgar, or simply feminine. She calls for the expression of the female body in its full complexity to transcend patriarchal norms that box in the feminine. Her work presents a pioneering voice in this struggle to empower the female body, as well as the female word.

Notes

1 Miral al-Tahawy, The Tent (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2010), Kindle edition, chap. 1.

2 Ibid., chap. 11.

3 Ariel M. Sheetrit, “Deterritorialization of Belonging: Between Home and the Unhomely in Miral

al-Tahawy’s Brooklyn Heights and Salman Natur’s She, the Autumn, and Me,” Journal of Levantine Studies 3, no. 2 (2013): 72.

4 Miral al-Tahawy, Brooklyn Heights, trans. Sameh Salim (London: Faber and Faber, 2012), 66, 68.

5 Aaron Bady, “Interview: Miral al-Tahawy,” Post45, November 8, 2014, accessed April 22, 2017,

http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/11/interview-miral-al-tahawy/.

6 George Orwell, “The Prevention of Literature,” in Books v. Cigarettes (London: Penguin Books, 2008), 33.

7 Hannah Ellis-Petersen, “Flowers or Vaginas? Georgia O’Keeffe Tate Show to Challenge Sexual Clichés,” The Guardian, March 1, 2016, accessed April 22, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/ artanddesign/2016/mar/01/georgia-okeeffe-show-at-tate-modern-to-challenge-outdated-viewsof-artist.

Writing the Body and the Rhetoric of Protest in Arab Women’s Literature

Miral al-Tahawy

(Translated from Arabic by Shoshana London Sappir)

“To my body, the peg of a tent, crucified in the wilderness.”

To this day I do not know why I chose to open my first novel, The Tent, with this dedication, despite all my attempts to cover the features of that body, whether by self-censorship, using rhetorical devices to connote and not denote meaning, or by pure denial of its presence in my writing obsessions.

At that time my body was enveloped in a hijab, disguised under the veils of virtue, and in harmony with tribal mores and the codes of shame. It was the body of a village girl who had learned the terms of social approval early on and evaded the sway of paternal supervision by making an emphatic show of puritanism and prudery. That was a girl who intuitively knew that modesty resides in denying her female identity. But writing came along, took my caution by surprise, and chose to uncover many of the features of the identity I was trying to disavow through denial.

Writing the female body and its representations in literature constitutes a fundamental theme in Arab women’s writing, not only as an expression of gender identity but also as a reflection of the peculiarity of the female space that is laden with diverse physical experiences such as motherhood, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. However, even though women’s writing acknowledges that connection between the body and the female identity of the writers’ selves, the prospect of incorporating the body into writing still arouses fears of the conservative tendency, which is apprehensive about the question of “the body in women’s writing.”

Numerous surveys have found that some female writers deny the sexual references implied by sexual and physical connotations. For example, if we asked a number of female writers how they construct the body in their writing, their answers are likely to be vague, dismissive, and evasive—for example, “the only body I celebrate is the body of imagination” or “so much can be written about the body without focusing exclusively on sensuality.” One writer summed up her philosophy: “I celebrate the body in my writing but in a conservative, inoffensive way.” [1] Despite its simplicity, this answer demonstrates the difficulties of expressing female identity in a society that still views it as an indecency, and writing about it as a risk that requires a high level of adaptation and self-censorship. This is because of the negative social connotations—such as vulgarity, promiscuity, and eroticism—attached to articulating the body when associated with women’s writing.

To me, these questions posed a dilemma. On the one hand, the focus on the body, its sensuality, and its presence in the works of my generation was a phenomenon that could not be denied. This generation of women was quite aware that women should free themselves from their fears and long history of subscribing to social decorum through claims of chastity and purity. On the other hand, there were concerns about preconceived ideas regarding this new women’s writing, such as being attention seeking, wanting to achieve undeserved fame, and getting translated into foreign languages through a sensual celebration of the female body. This celebration is reflected in the titles of these novels, their “dedications,” and the issues they tackle—issues that focus primarily on the body as a main theme.

I cannot deny that I was asked some of these accusatory questions in many interviews: “Do you believe writing about the body is the path to fame and popularity as a writer?” “What do you think about body writing?” “Do you consider your works part of the body-writing trend in Arab women’s fiction?” I would try to evade the implicit accusation of making big rhetorical statements by giving answers that bear contradictory meanings. Most of my answers were statements about how the body is a more profound concept than the sexual body, that writing is not a medium for pornography, and so on. My answers were charged with that anxiety, that fear of classification and straitjacketing, of reducing these new works to nudity to attract readership.

That conditioned association between the body in female writing and obscenity and scandal led many Arab women to deny their physicality in their writing for many years and to focus only on the purity of the body and maternity. They generally did this by trying to comply with social taste, and they attempted to avoid the risk of expressing their sexual identity by denying it or obscuring it, so that the female body became nothing but a metaphor for the homeland or the nation. That conservative tendency was expressed by numerous romantic and social female writers who had reconciled with the values of patriarchal society. However, conservative writing was definitely not the only trend in women’s writing.

Women’s Body: Writing Body

Women’s writing is often critically received like a body: laden with sensual seduction or sexual temptation. Female presence in writing arouses, in both readers and critics, sensual and erotic fantasies that inspire a metaphoric association between a woman’s body and her writing. For instance, women’s writing is often described by way of praise as a “living feminine body,” which allows the recipient to project historical conceptualizations of femininity onto it. Such descriptions also subject women’s writing to the same contradictory social practices that are applied to women’s bodies, such as curiosity about it, lust for it, voyeurism, violation, dispossession, overinterpretation, and implicit criticism of it as weak and inferior.

This imaginary presence of the woman’s body in her writing added openly sensual terminology to the critical reception repertoire, whether in praise of the feminine text or flirtation with the writer. For example, the female author is often described as, “the beautiful young woman,” or her writing is described using flirtatious and sensuous adjectives, such as beautiful, graceful, erotic, daring, sensual, or freshly bloomed. Use of these adjectives in such descriptions is sure to stimulate erotic fantasies in the Arab reader. [2]

Furthermore, male Arab critics have often reduced the aesthetics of female writing to the acts of “revealing” and “undressing.” Therefore, female writing of any kind connotes “undressing,” a word often used as a synonym for writing. Even the writing itself is often described as “naked” or “revealing.” Such texts are often praised as “a rebellious body of writing that reveals and exposes society by exposing itself.” Critical praise idolizes the act of undressing in both its social and psychological aspects. Good writing is writing that performs its role of “revealing the unspoken in Arab society,” and sometimes “unveiling what is hidden,” “baring what was covered,” “stripping reality,” “dropping the veils of historic fear of disclosure and revelation,” or “stripping bare the reality enveloped in a cloak of modesty.” These recurring critical clichés implicitly mix sensual connotations with the lust that comes with lewdness, so that any revelation of the female body becomes a symbolic seduction.

That metaphorical connection between women’s bodies and writing induced a kind of lust in patriarchal critical reception. This manifested in the titles of critical reviews of the new women’s writing, which refer to how the writers perform “a kind of seduction” by revealing women’s feelings, leading one researcher to title his study “The Delight of Women’s Storytelling and the Factors of Arousal and Seduction.” [3]

It also led another critic to title his critical study of a poetry collection by a female poet “Amorous Verbs and the Structure of Desire.” His study begins with these words:

Women’s acts in the field of writing use seduction of a special kind, especially in its overall reception and by constructing the female body and writing about it with an increasing number of symbols. It sets a condition that became a standard for so-called “women’s writing,” for the female body to twist through female text, baring it and exposing it to comments, surveillance, and blame. [4]

The connection between women’s writing and shamelessness, obscenity, and immorality (and hence, arousal and lust) is rooted in Arab history. According to critic Abd Allah al-Ghadhdhami, women’s writing is associated in Arab culture with many of the concerns raised by numerous traditional Arab texts, which associated writing with immorality. Eloquence and fervor were synonymous with virility, and so were monopolized by males for cultural and religious reasons. These reasons described women’s voices as an indecency, and made their physical body something to be veiled, hidden, and covered. The representation of a free woman in Arab society is that of a fertile, amiable, chaste woman whom no one sees. Subsequently, free women were prevented from engaging in writing as a way of forcefully protecting their chastity. During that period writing—along with literature and music—was associated with the obscenity of female slaves. This made it forbidden to teach free women to write, on the assumption that the women would learn to write in order to correspond with men, which meant sending flirtatious letters to seduce them. In that sense letter writing became an instrument of moral corruption and obscenity, as expressed by Khair u-Din Ni’man bin Abi a-Thana’ in his work “The Purpose of Preventing Women from Writing.” [5] Only female slaves were allowed to expose themselves before strangers—the hijab was no religious obligation for them—just as in the past they were allowed to write, which increased their worth.

The emergence of women’s writing in the modern age coincided with the act of lifting the veil and removing the hijab. Since the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the discourse of women’s liberation has been associated with a battle against the conservative religious forces surrounding the removal of the veil. Women’s participation in public life and in writing represented a great part of that struggle. This act of lifting the veil carried broad political and social significance, but it carried negative connotations as well, considering that it was tantamount to “nudity.” The call for lifting the veil went beyond getting rid of face veils and letting go of the hijab as articles of clothing. It was also about being present in society and participating in public, literary, and intellectual life— especially since many of the pioneers of women’s liberation were scholars who were famous for their eloquence and had published pieces in newspapers and magazines. Despite all this, women’s writing in that context constituted a break from convention and, simultaneously, a flirtation with the male world. Literary salons are the most prominent example of that interpretation.

Women’s writing and the lifting of the veil constituted a breach in the isolation imposed on women’s worlds, and as Fatima Mernissi argues, the hijab was less an item of clothing than it was a symbolic erasing of women’s presence from the public sphere. Writing represented the primary form of being present in that public sphere, and as long as it constituted the deepest expression of presence there, it remained associated in the Arab mentality with the act of undressing and unveiling—that is, “nudity”—thus summoning both desire and shame. [6]

There is no doubt that female creativity is a metaphorical “undressing” of patriarchal culture and the reality that men promote. Al-Ghadhdhami’s analysis of the Thousand and One Nights story, “The Seductive Slave Girl,” outlines the symbolic connection between women’s writing and exposing male culture. The “seductive” slave girl Tawaddud debates men to prove that she is more knowledgeable, cultivated, and well-mannered than the caliph’s entire entourage. Every man she defeats in the debate tears off his clothes, leaving him literally naked, defeated, and admitting that a woman surpassed men in terms of education and poetic ability, until they all end up naked before her. This slave girl denudes male culture, illustrating an anachronistic irony: “femininity denuded masculinity.” [7] She also proves that a reading of the body rhetoric in Arab narrative discourse and its evolution from disavowal to disclosure cannot ignore the historical and cultural contexts in which women’s writing emerged and flourished.

The Female Body as an Instrument of Protest

The association between physicality, sensuality, and the female text is a historic one that was not fully created by the female text; rather, it was associated with the social markers of femininity and its presence outside the context of concealment. The female text carried a number of expectations about how it would be received. Mainly, those expectations were revelation, undressing, unveiling, violation, and then, desire and lust. Those are signs that sometimes do not arise from the text itself so much as from the act of female writing and its historic and cultural significance. The lust surrounding the reception of the text in many cases does not reflect the eroticism of the text itself; rather, it reflects the male lust associated with revealing the world of the harem.

Female Arab criticism attempted to make the connection between female writing and the significance of the acts of revelation and undressing in a different context; it also tried to make reading female writing a form of protest rather than seduction. Women’s writing leans toward revelation because it signifies a social and political reaction to women’s concealment and marginalization, and at its core it is an act of protest. In this regard, Khalida Saeed says that “the act of writing for women in particular is a liberating act because it is awareness, positioning, and exposure of experiences and sufferings and imaginations and needs and dreams that have long been silenced and concealed—writing crystallizes them and takes them out into the public domain.” [8]

Another critic sees undressing in women’s writing as a reaction to the history of prohibition:

The relationship between women and writing has the aspect of revelation and nakedness: since women are the most repressed and disadvantaged group in society, writing becomes a great space for them to characterize all of the features of that repression and prohibition. [9]

Despite the expectation that women’s writing grows from the landscape of desire associated with prying into the concealed world of the harem, the discourse of women’s writing about the body is not at all based on eroticism. On the contrary, the texts that escaped self-censorship and managed to express their eroticism in the past and present are fairly rare in Arab women’s narratives. Of course, this does not negate that the body was present in such writing, operating within the social, cultural, and political struggles, or that women’s writing and their bodies were two aspects of a long struggle for liberation. The connection between women’s bodies and women’s writing and the women’s liberation movement is not new. After all, women’s writing in one form or another is one of the manifestations of the feminist movement—its discourse of liberation, its demands to liberate women’s bodies, and its effort to reveal and expose women’s status in the Arab and Islamic world, especially when it comes to physicality and gender identity.

The emergence of the Internet and the expansion of the space to publish and use nicknames in writing—as well as the social evolution that gave writing the green light to be explicit, especially concerning a woman’s sexuality and relationship with her body—was instrumental in developing representations of the body. In other words, the rhetoric of writing the body evolved—from denouncements and condemnations of the values that imprisoned it to protest against those values by revolutionizing the rhetorical discourse of rebellion. The body was no longer the object of oppression but rather an instrument of protest against that oppression. This development in the rhetorical discourse of the body can be seen through the course of several generations.

The first generation of women writers in the 1960s—writers such as Latifa al-Zayyat, Nawal El Saadawi, Ghada al-Samman, and Laila Baalabaki—were concerned with women’s social affairs, and they expressed a clear feminist ideology, adhering to the rights rhetoric that condemns patriarchal society for enslaving women’s bodies. Their writings exposed patriarchal authority and condemned all forms of women’s oppression. The female body played a prominent role in that generation as a theme of protest. Those pioneering writings raised conservative social issues related to the female body such as forced and premature marriage, virginity, pedophilic males assaulting young girls, sexual violence as an instrument of subjugation, and issues of honor crimes and their role in condemning women’s bodies and limiting their freedom. This writing also reflected the social chains imposed on the female body by the patriarchy, as well as other subjects that concerned most of the women writers.

The liberation of the female body from the reign of rigid conventions and traditions was the primary obsession of women’s writing. Perhaps the most noteworthy of the literary experimentations of that generation is that of Egyptian writer Alifa Rifaat, whose sensual writing about the body during the 1960s aroused fierce controversy and sometimes even bans and confiscations. Her bold writings led to her classification as the pioneer of erotic writing in women’s literature.

Even though the female body has preoccupied women writers since the 1950s, it was presented as a victim of male practices and an instrument of social enslavement. Whether feminist discourse was fundamental to those texts or marginal, the writing fought to liberate that body from the dominance of patriarchal society.

The female body remained women’s obsession in writing and the axis of women’s pain, while the representation of that body took on more radical forms of rebellion over time. For generations, writing the body was not limited to condemning society for the body’s enslavement: it also challenged society through the body itself, whether by its sensual affirmation or by using explicit sexual language to emphasize its being a sexual entity with its own desires—desires that should not lead to shame or concealment. The rhetoric of body writing developed and changed from timid demands for the body’s rights to the use of sexuality as a tool to shame society’s hypocrisy for its views on virtue, chastity, and the concept of honor.

Beginning in the early 1990s, a number of critics noticed the emergence of a new trend in women’s narrative writing, one that celebrated the body in an ambivalent way that was shocking to the prevailing taste in critical reception, which Egyptian author Edwar al-Kharrat dubbed “girls’ narrative” and “body narrative.” These terms would lay the groundwork for the emergence of a number of female writers in the 1990s whose writing expressed their sexuality more clearly. A special boldness and the desire to employ the female body more radically within the text characterized most of that generation’s writings. In the attempt to predict that transformation and with the increase in the glaring presence of the feminine with all its uniqueness, special language, and awareness, that writing was metaphorically named “body writing.” At its core it is a literary experience that “attempts to establish a kind of female writing that challenges narrative conventions and norms to construct the domain of female knowledge, presence, spirit, and body, to place its esthetic order and structure beyond the patriarchal order that still governs Egyptian Arab women’s narrative creativity.” [10]

Many female writers, such as May Tilmisani, Nura Amin, and others, came from that generation. Perhaps the most prominent representative of that literary trend was Mona Prince: in her novel So You May See, she demonstrates unusual audacity in the expression of her sexuality as a female within the text.

The phenomenon was not merely Egyptian but more broadly Arab, and it included a great many authors from all Arab countries. Their works won critical acclaim and were translated into numerous languages. The body was the axis of these writings, as can be seen in their telling titles: Memory in the Flesh (Ahlam Mosteghanemi), The Proof of the Honey (Salwa Naimi), The Feminine of Shame and The Discovery of Desire (Fadhila Al Farouq), The Smell of Cinnamon (Samar Yazbek), Passion (Aliya Mamdouh), and The Cursed Novel (Amal Jarah).

The trend reached as far as the Arabian Gulf and Saudi Arabia, spurred by the increase in the use of pseudonyms, which allowed experiments that were far more daring than anything previously imaginable in women’s literature—in, for example, the novel The Others, by Saba Haraz, The Return, by Warda Abdul Malik, and others.

With their titles and content, these works broke the taboos that social acceptance had imposed on women’s bodies. They also ventured into the land of the forbidden through their sexual themes and thorny subjects such as incestuous and homosexual relationships and explicit language in describing the body and its whims, lusts, and even deformations. All of these texts were characterized by their refusal to adhere to the expected conventions of women’s writing. These conventions had for decades pushed women’s writing toward relying on symbolism, overromanticizing, self-censorship, and conservatism, as well as exaggeration in using connotation as a rhetorical alternative to denotation.

Thus began the new women’s trend in writing, which no longer hid under linguistic metaphors overloaded with symbols, but rather opted for creating texts up to the challenge and seeking to shock and startle. These texts offered

a female view of the world and criticism of patriarchal culture, disrupting the recipient’s beliefs and conceptions of what is suitable for a woman to write about. This was a new form of writing that moved in seemingly forbidden territories and revealed the desires of the body and upset social harmony because it repeatedly cut itself off from tradition, expectations, and prevailing norms. [11]

Writing the body emerged simultaneously with the first signs of the Arab protest movements that came before the Arab Spring uprisings. It was also concurrent with the emergence of new forms of protest that had recently been employed by women’s movements, such as nude protests, and the rise of the religious right that reinforced the concept of the body as sin in Arab societies.

This writing raised numerous questions about its nature: Was it erotic writing or protest writing reflecting one of the forms of social, political, and sexual turbulence of a society on the brink of explosion? How did the Internet and pseudonyms contribute as tools for bypassing censorship? How did this phenomenon proliferate in the shadow of a social reality of paradoxes, the rise of the radical religious tendency in the Arab world, and the resulting upsurge of sexual violations of the Arab female body?

There is no doubt that the emergence of that tendency in women’s writing rose in the shadow of a parallel social and political background. The close-knit relationship between the rise of women’s writing and the emergence of women’s protest (by undressing) inspires contemplation of the three-way dynamic relationship between female writing that shocks the reader, protesting in the nude as a female political statement, and the rise of the conservative religious discourse that reviles women’s bodies. This dynamic points to a belief that this literary phenomenon did not rise out of a vacuum, but is essentially a phenomenon of protest fueled by political and social causes.

These reflections lead us to a number of preliminary observations: First, the relationship between the body and protest is strong and rooted in the body’s historical representation as both an object of oppression and an instrument of protest. The human body, male and female, has often been used as an instrument of protest. In many cases, manifestations of the body have served as protest either by acceptance or rejection, just as the body has been used politically by subjugating and violating it in torture and coercion.

Arab women’s bodies have historically been subjected to all kinds of coercion: mutilation (circumcision), harassment, rape, or undressing with the intent to disgrace, such as when suspecting that a wife has been unfaithful. Women’s history has known numerous forms of protest using the body, including self-immolation, which occurs in Arab societies when families force their daughters into marriage, or because of a husband’s misconduct. Recently, during the Arab protests and uprisings, self-immolation became the first manifestation of protest, a manifestation that women inspired men to use. [12]

Most recently, the protest movements, particularly in Egypt, witnessed numerous forms of physical and sexual violations of women’s bodies in the political sphere, and sexual harassment was employed as a political tool to restrain women in protests. [13] The systematic violation and undressing of victims’ bodies to intimidate them and keep them from participating in protests has been documented by many human rights organizations, and this tactic followed “specific instructions aimed at humiliating women.” [14]

The targeting of women’s bodies increased after radical religious groups rose to power after the Arab Spring. In political conflicts some radicals use organized, systematic targeting of women’s bodies to terrorize them and limit their participation: these bodies are used as an instrument of political blackmail. Currently, some radical religious groups are targeting religious minorities by enslaving and selling the bodies of their women—another form of political extortion focused on women’s bodies. [15]

Second, it is impossible to overlook the connection between the violations to which the female body is exposed and the dominant Salafi Islamic legal discourse, which has had a major bearing on reviling and loathing that body. Despite attempts by the more enlightened Islamic scholars and intellectuals to defend Islam’s positive attitude toward women and to emphasize that Islam respects women and is concerned with protecting their bodies, extremist radical discourse continues to use its power to interpret the religious texts surrounding women and their bodies. That discourse continually diminishes the value of women as people and focuses completely on their bodies, which the extremists consider the source of temptation, seduction, and incitement to sin. This discourse has recently found political channels to voice its ideas and has caused a great deal of controversy, specifically regarding women and their bodies.

Such rhetoric has led to strict adherence to dress codes and the oppression of the female body with some forms of clothing. This backward outlook, which was revived in recent decades, did not just diminish the social gains of the women’s liberation movement; we can also say that “as Islamic radicalism rose at the beginning of the last decade, the pendulum for Muslim women swung the other way again. Once more they were to be hidden behind veils, a development that now seemed to legitimize and institutionalize inequality for women.” [16]

Nasr Hamed Abu Zeid examined the decline of Arab women’s status, produced by the Salafist religious discourse about them in the contemporary Arab world, and described it as a predominantly sectarian and racist rhetoric that turns women into “an erotic object that induces urges and impulses, an object of seduction and the devil’s snare, etc. The only solution can be to ‘bury women alive,’ as Arabs did in the pre-Islamic era, except that now they ‘bury’ them in black clothes that fully cover them, leaving only an opening for the eyes, which is literally tantamount to burial above the ground.” [17]

Third, the rise of a new wave of the feminist movement, the nude protest movement, established the use of women’s bodies as a tool of protest. The international and Arab women’s protest movement witnessed previously unheard-of manifestations of protest, such as resorting to nudity to protest social or political conditions. This occurred as a response to the new means of protest presented by the women’s movement FEMEN, and that movement spread to the Arab world through a number of Arab women who undressed to protest political conditions, whether in the streets or public squares or on their personal social media pages.

For instance, the famous Iranian actress Golshifteh Farahani published a photograph of herself half naked on her Facebook page to protest the policy of sexual discrimination in her country. Artist Hala Faisal completely undressed in Washington Square Park in New York to protest the war in Syria. [18] Egyptian activist Aliaa Elmahdy published a completely nude picture of herself with the caption, “This is my body,” then went on to repeatedly publish naked pictures of herself as an act of voicing protest against women’s conditions in Egypt after a revolution that failed to change those conditions. [19] Several Tunisian women activists also staged nude protests, and the Tunisian women’s rights activist Ameena Taylor published nude pictures of herself on the Internet as an act of protest. [20] Moroccan artist Latifa Ahrara stripped on stage in front of an audience to protest the Islamic attitude toward art. [21]

Nude protesting constituted a social blow and set off extensive controversy, even within the liberal movement, about women’s right to use undressing as a means of protest. Many conservative female voices condemned nude protesting, and some activists demanded that the protesters adopt other forms of protest and political participation.

Like nude protesting, Arab women’s writing and its rhetoric are not separate from the social and political context, just as they are not far removed from the cultural context in which women’s bodies are exposed. Therefore, it is impossible to read this new tendency called “body writing” and women’s narratives as if they were an erotic trend, despite the sometimes extreme use of pornographic language and sensual and licentious imagery, because the written texts still contain a significant potential to challenge and rebel against the male world.

Furthermore, the emergence of that writing exposes the strong relationship between excessive use of explicit language and tackling sexual taboos and the rise of the religious extremist discourse’s influence in spreading ideas that emphasize the impurity of the female body and reduce it to genitalia. By now it has become clear that the more the conservative discourse reviles and oppresses the female body, the more extreme is women’s reaction of using that body as an instrument of protest, in ways that the Arab world has never seen before.

Notes

1 Nouara Lahreche, “al-Katibat Arabiat wa qadaya al-jasad” [Arab female authors discuss writing the female body], al-Noor, October 14, 2009, online survey, accessed April 24, 2017, http://www. alnoor.se/article.asp?id=59992.

2 See Sabary Hafez’s series of articles discussing 1990s women writers such as Nora Amin, May Eltelmesany, and Miral al-Tahawy, al-Musawer Magazine, Feb.–Aug. 22, 1998. See also another series by critic Ali al-Ra’ay in the Egyptian daily al-Ahram, issues from July 1996. Shukri Muhammad ʽAyyad, “Nisaʾuna al-saghirat yuʿallimunana al-hubb” [Our little women teach us love], al-Hilal, issues from July, August, and September 1998; Faruq Abdel-Qadir, “New Scene of the Egyptian Novel: Half of the Novelists Are Ladies,” in the Lebanese as-Safir, issues from July 2 and August 2, 2002; and Shereen Abou El-Naga, ʽAtifat al-ihtilaf: Qira’ah fi kitabat niswiya, [The sentiment of difference: Readings in feminist writings] (Cairo: al-Hayʾah al-Misriyah al-ʽAmmah lil-Kitab, 1998).

3 Al-Akhdhar bin al-Saeh, “Ladhdhat al-sard al-nisaʾi wa-ʽawamil al-itharah wa-al-al-Ighraʽ,” Nizwa Magazine, issue 64, Amman, December 12, 2010, accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.nizwa.com.

4 Abdel Nur Idris, “al-Ishtihaʾ wa dawaʾir al-samt: Qira’ah fi diwan sahwaat al-rih li Malikah Bemansur,” accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=302404.

5 Abd Allah Muhammad al-Ghadhdhami, Thaqafat al-wahm: Muqarabat hawla al-marʾah wa-al-jasad wa-al-lughah [Women and language], 3rd ed. (Beirut: Arab Cultural Center, 2006), 112.

6 Fatima Mernissi, Beyond the Veil, trans. Fatima al-Zahra Azweil, 4th ed. (Beirut: Arab Cultural Center, 2005), 155.

7 See al-Ghadhdhami, Thaqafat al-wahm, 88.

8 Khalida Saeed, Fi al-badʾ kana al-muthanna, Khalidah Saʿid (Beirut: Dar al-Saqi, 2009), 178.

9 Zuhur Karam, al-Sard al-nisaʾi al-ʽArabi: Muqarabah fi al-mafhum wa-al-khitab (al-Dar al-Baydaʾ: Sharikat al-Nashr wa-al-Tawziʿ al-Madaris, 2004), 63.

10 Abd al-Rahman abu Awf, “Qiraʾh fi al-kitabah al-nisaʾiyah [The generation of the nineties: Reading in women’s writing], al-Ahram Democracy Magazine, accessed April 29, 2017, http://democracy.ahram.org.eg/UI/Front/InnerPrint.aspx?NewsID=337.

11 Bin al-Saeh “Ladhdhat al-sard al-nisaʾi.”

12 For example, Mohamed Bouazizi was a Tunisian man who set himself on fire. See “What Drives an Ordinary Man to Burn Himself to Death?” New York Times, January 21, 2011.

13 Editorial Board, “Terror in Tahrir Square,” New York Times, March 28, 2013, accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/29/opinion/terror-in-tahrir-square.html.

14 To read more about the systematic violation of the female body, see Ruth Whitehead, “Muslim Brotherhood ‘Paying Gangs to Go Out and Rape Women . . . ,” Mail Online, December 1, 2012, accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article2241374/MuslimBrotherhood-paying-gangs-rape-women-beat-men-protesting-Egypt-thousands-demonstratorspour-streets.html.

15 To read more about systematic sexual harassment in Egypt after the 2011 revolution, see Bisan Kassab and Rana Mamdouh, “Afat al-al-taharrush fi Misr,” al-Akhbar al-Lubnaniya, April 29, 2012, accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.al-akhbar.com /node/166868.

16 Jan Goodwin, Price of Honor: Muslim Women Lift the Veil of Silence on the Islamic World (Boston: Little, Brown, 1994), 31.

17 See Nasr Hamed Abu Zeid, Dawa’ir al-khawf: Qira’ahfi khitab al-mar’ah [Circles of fear: Reading the discourse about women] (Beirut: Arab Cultural Center, 1999), 38.

18 Mohammad Yassin al-Jalassi, “FEMEN Stages Nude Protest, First in Arab World,” al-Monitor, May 30, 2013, accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/culture/2013/05/ femen-nude-protest-tunisia.html#ixzz2WynU0wjd.

19 “The Naked Revolution,” SBS, April 16, 2013, 3:47 pm, accessed April 29, 2017, http://www.sbs.com.au/news/dateline/story/naked-revolution.

20 Al-Jalassi, “FEMEN Stages Nude Protest.”

21 See Loubna Flah, “Actress Latifa Ahrara and Public Nudity,” Morocco World News, December 14, 2011, 12:31 a.m., accessed April 29, 2017, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2011/12/19052/ actress-latifa-ahrara-and-public-nudity/.

Leave a Reply