Shedding Some Darkness on the Light: Night and Night Life in 18th-Century Istanbul

by Avner Wishnitzer, Tel Aviv University

On September 8, 1790, a small group of European sailors set out for a night of merrymaking on the waters of the Bosphorus. Such nighttime sailings were common, but this group was particularly rowdy and very near the imperial palace, where the sultan, Selim III (1789–1808), was trying to sleep. The next morning, the tired and angry sultan sent the following order to one of his senior officers:

Last night, toward the morning, Frenk sailors [sailed] with a boat back and forth several times in front of the palace while singing songs. Order the Chief Scribe to warn all ambassadors and Europeans never to perform this shameless act [again]. I will mercilessly kill whoever does it . . . Let him [the Chief Scribe] issue a stern warning.

From the sixteenth century, the Ottoman sultans maintained a distance from their subjects, in a way that was meant to enhance their aura of unattainable power. They stayed hidden in their palaces, appearing in public only surrounded by a huge retinue, which also demonstrated the ruler’s power and wealth. The rowdy sailors had entered the forbidden area under cover of night. They were too close. The angry order, therefore, was intended to mark the boundaries that the night threatened to blur. The order demonstrates that the night is not merely a darker version of the day. Darkness shapes social interaction in different ways, which may vary from one society to another and from one geographical area or historical period to another. The night, in short, has a history.

Joseph Warnia Zarzecki- Sultan Selim III (Google Art Project)

In recent decades, scholars in various fields have begun to examine diverse aspects of the dark hours. Artificial lighting and its cost receive special attention. Whereas in the past, the amount of artificial light a society produced was viewed as a clear measure of its degree of “enlightenment,” recent studies emphasize the economic, ecological, and health costs of excessive lighting. Governmental agencies and nongovernmental organizations disseminate information on the negative effects of excessive lighting and promote regulations and laws that limit “light pollution.” Darkness, which for generations was identified with danger and evil that must be banished by means of light, is now perceived increasingly as an important interval that must be protected. Clearly, the groups acting to limit lighting are not seeking to return humanity to “the darkness of the Middle Ages,” but rather to develop means of more economical, environment-friendly and healthy lighting. To use the words of one of the leading researchers in this area, “It seems that a brighter future for mankind may in fact be a darker future.”

The critical approaches to excessive lighting have increased the interest in the history of the night. Consequently, in recent years a number of important studies have appeared that reconstruct various aspects of night life in past societies. Research in this area in the Middle East is still in its infancy, but it has already yielded several interesting insights. In contrast to the common assumptions that before the introduction of street lighting people in the Middle East went to sleep “with the chickens,” new research has uncovered a number of night-life traditions that had social, political, and cultural roles.

For some, the hours of darkness were a time for seclusion. Sufis, for example, found convenient conditions in the quiet and darkness for turning inward “and gazing on the mirror of the heart,” as they often called it. The eighteenth-century Sufi poet Erzurumlu Ibrahim Hakki wrote:

The eye of the people of love is awake at the time of dawn/ The soul of the people of the heart is filled with secrets at the time of dawn/ The town of the heart is quiet at night, without the common crowds/ The feast of the soul [bezm-i can] takes place without the distress of strangers at the time of dawn.

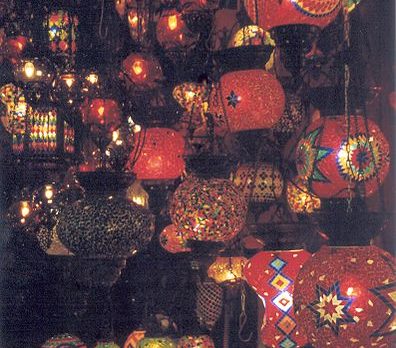

For others, the night was a time for other kinds of feasts. Hundreds of taverns and other alcohol-selling businesses that operated primarily in the Christian neighborhoods of Istanbul served customers, Christians and Jews, but also Muslims who took advantage of the dark to slip away from peering eyes and drink wine and rakı. Coffee houses and hamams too were venues for night life, dubious sometimes, but very popular. In all of these places, night allowed what the day forbade. From the perspective of many of the city’s inhabitants, nighttime was an opportunity to escape the surveillance of neighborhood, guild, and family, all of which served as mechanisms of social control. Darkness allowed slipping between the cracks of the social order without being seen. This was the time of drinking parties, dalliances, and extramarital sexual relations.

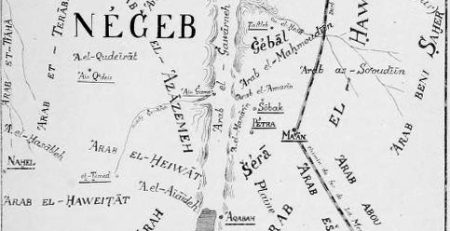

The sociopolitical structure of the Ottoman Empire and the physical surroundings of Istanbul created traditions of nighttime entertainment, some of which were unique to particular social groups and some of which cut across class and community lines. One of them, which was common at least from the seventeenth century, was sailing on the Bosphorus. On full-moon summer nights, groups of revelers would participate in “floating parties” in boats that sailed in unison as one block, with musicians, singers, food, and often alcoholic beverages on board. Usually, parties were paid for by a wealthy person, demonstrating his power and benevolence. The projection of the moonlight on the dark water (known as “silver cypress”) and the sounds of the oars and the music in the quiet of the night were immortalized in poems and songs, some of which were recited or sung on those very boats. In other words, nighttime entertainment did not rely on banishing the darkness and transforming the night into day, but rather sought to sensitize participants to the unique experience of the night. Here is an example from a poem by Naşid (d. 1791):

My young boy, let us be satiated with a cup of pure wine / Let us drink so much that we let loose our inhibitions / Come on, don’t recline to sleep this early, my lord/ Oh, [you] moon on the summit of grace, let us go out to the full moonlight/ One or two lutes we need, and a few good singers/ They should sing night tunes and play teasing music at times/ Let us alight at the meadows of Küçüksu for a while / Oh, [you] moon on the summit of grace, let us go out to the full moonlight

Commoners’ traditions of nighttime entertainment were a challenge for the authorities, because without cheap and effective lighting technology they could not be monitored effectively. In this sense, the sultan’s anger toward those rowdy sailors with whom I opened was literally “blind.” Whereas people who disturbed the sultan’s peace in daytime were caught immediately, those sailing at night were hidden from his sight and thus beyond his reach.

To cope with crime and political subversion, which operated under cover of darkness, the Ottomans used a variety of tools aimed at monitoring and reducing nighttime traffic in the city. For example, the gates of walled cities were closed at dusk, and so were the gates of the quarters, neighborhoods, markets, and other closed compounds. Armed guards roamed the streets and arrested anyone walking without a light. However, as we have seen above, despite all the measures of control, the night had its own life.

Gaslight arrived in Istanbul around the middle of the nineteenth century and led to a dramatic change in the nature of night life in the city, and gradually in the other cities throughout the Middle East. Artificial light contributed to a sense of security among the inhabitants and opened up new possibilities for nighttime work and entertainment. However, just as the accelerated urbanization of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries created urban spaces that resembled each other, while erasing the differences between habitats and destroying ecological systems, artificial light erased unique nocturnal experiences and destroyed local traditions of nighttime entertainment. When assessing the spread of street lighting, then, it is worth noting along with the obvious advantages of artificial light the loss of cultural plurality that accompanied the process. The lost world of darkness is worth reconstructing not for the sake of nostalgia, but rather as new angle from which to examine the modern, hyper-illuminated night, an angle that may allow us to imagine alternatives. It is possible that we too, in the twenty-first century, can benefit from a little more darkness and a little more quiet, to stop for a while and turn inward, or to sing together, away from the eyes of the sultan.

* I wish to thank Walter Andrews and Selim Kuru for their invaluable assistance.

Leave a Reply