Photomontage: Shy Abady’s Augusta Victoria Series

Shy Abady (1965) was born and grew up in Jerusalem and now lives and works in Tel Aviv. He is a graduate of the Beit Berl School of Art (Hamidrasha) and is completing a master’s degree in art history at Tel Aviv University. Abady has created several series in which the central axis is biographical, tracing the lives of figures such as Vaslav Nijinsky, Hannah Arendt, and the poet Radu Klapper. In Berlin, between 2007 and 2008, he created the series titled My Other Germany, which moves along the historical-political axis while focusing on German sculptures and memorials. In addition to Abady’s drawings and paintings, a large part of his work in recent years has been based on techniques involving electrical etching on wood.

Since 1995 Abady’s works have been exhibited in one-man and group shows in Israel and abroad. Among his one-man exhibitions in recent years are The Hannah Arendt Project (2005: The Jewish Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; 2006: Jerusalem Artists’ House, Israel; 2010: Beit Hatfutsot, Tel Aviv, Israel); The Revolution that Danced (2009: Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center, Israel); Radu (2012: Zadik Gallery, Jaffa, Israel); and Augusta Victoria (2012: Dan Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel).

In 2000 Abady received a fellowship at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, sponsored by the Council for Culture and Art. In 2011 he received the Israeli national lottery (Mifal Ha-Payis) support fellowship to produce the catalog for the Radu series.

To see more photos from the series, see Abady’s website here.

On the Photomontage

by Zohar Kohavi

In the black distance

gallops are sown of unseen horses

that are melting away. [1]

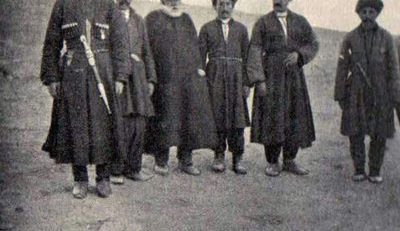

Shy Abady’s Augusta Victoria series, six of whose thirteen images are presented here, focuses on two families: that of Binyamin Ze’ev (Theodor) Herzl (1860–1904), visionary of the Jewish state, and that of the last German emperor and empress, Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941), and his wife, Augusta Victoria (1858–1921).[2] Abady focuses on the interaction between Herzl and Wilhelm II, relating to the fates of their two families as an allegory of the fates of the Jewish and German peoples, as well as that of the Palestinian people. The use of first names for many of the titles (Theodor, Victoria Louise, Joachim, Hans, Augusta Victoria, Wilhelm) suggests that the personal may be used to peruse the public: the portraits of individuals highlight the individual as the bearer of the political, and through this ensemble one sees the line that links the past to the present, and perhaps even to the future, like a pair of compasses moving in widening circles. Indeed, one of the motifs in this series is a line—a line that not only connects the works to each other but also expresses the connection the series makes between history, fate, and private and public worlds, linking them to our time while hinting at the posttraumatic nature of the present. Both families suffered similar tragedies, some of which are expressed in the series. For example, Hans, Herzl’s son, shot himself to death, as did Joachim, the son of Augusta Victoria and Wilhelm II. Through these two families Abady pinpoints coordinates, like dots that we must connect in order to see the historicopolitico-cultural picture. Alongside it—in a manner analogous to that of a hologram that shows the next possible move—he offers an alternative to that picture: the promise, either real or imagined, that lay in the meeting between Herzl and the kaiser. What would have happened, for example, if the kaiser had chosen to help Herzl establish the state of the Jews at the end of the nineteenth century? And if he had helped, what would the Judeo-Palestinian space look like today?

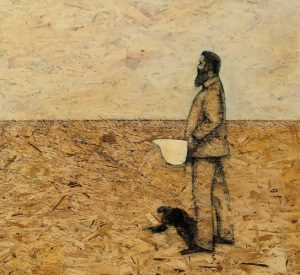

I

Herzl, the father of political Zionism and the founder of Zionism as an institutionalized movement, was born in Budapest. When he was eighteen he moved with his family to Vienna, where he completed his law studies and worked in journalism and as a writer of prose and plays. As part of his efforts to realize his vision of a Jewish state, Herzl sought Wilhelm II’s help in influencing the Ottoman Sultan to grant a charter for Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel. He finally succeeded in obtaining a brief audience with the kaiser in Constantinople, and they had two more meetings in 1898 in the Land of Israel: one near Mikve Israel and the other in Jerusalem. These meetings, however, were a disappointment; it became clear that the kaiser, having learned of the sultan’s opposition to the idea, was no longer willing to try to influence him. The photograph on which the image Theodor is based is the documentation of Herzl’s meeting with Wilhelm II near Mikve Israel in October 1898. It became apparent during the development process that the photograph taken by David Wolfson was unusable, and therefore the meeting had to be documented by photomontage. Herzl was photographed again, this time on his own, in Jaffa. And that was how the picture familiar today was assembled. In a manner not lacking in symbolism, for the purposes of the photomontage the kaiser’s image, captured by the original photograph, was transferred from the white horse on which he had been riding to the black horse that had been standing behind it. A hint of this assemblage is evident in the image of the black horse (The Horse), whose head is covered by a white mask. One might say that Herzl is the modern incarnation of the biblical Moses. Moses led the Israelites to the land of Canaan, and to that end he negotiated with the pharaoh; Herzl negotiated with the kaiser, and other rulers, to promote a similar, perhaps even identical, idea. Both brought the Jewish people to where it lives today, and both, despite the task they had taken upon themselves, were in some sense outsiders; perhaps that is why neither of them was privileged to enter the Promised Land. Moses was not privileged to enter the Land of Israel in the physical sense, and Herzl was not privileged to enter in the political sense.[3] Like Moses’s efforts to bring the Israelites to Canaan, Herzl’s were somewhat surprising—a kind of improvisation that did not appear in the original script. The tension embodied in Herzl the private person corresponds to the foreign, ambivalent affiliation of the Jewish people with this place. Herzl was a Jew who, until he covered the Dreyfus trial, was assimilated and secular—but with the appearance of a semi-ultraOrthodox Jew—and a European who strove to reach the Land of Israel. Like Herzl and the kaiser—who met in Mikve Israel, but whose meeting was memorialized in a semi-artificial way—the Israelites lived in this region as authentic natives but are here today in a semi-artificial way: belonging and not belonging. Coming home is an understandable longing, but sometimes it seems that it is perfect only as a desire—that is, as long as it is not realized. [4] In a certain sense the return of the Jews to their land is comparable to the return of the adult to his parents’ house. One cannot defeat the laws of nature; in his parents’ house he becomes a child and must grow up again.

Shy Abady, Theodor, 2010, Electric etching and oil on OSB, 120x130cm. Copyright Abady.

II

Augusta Victoria, the church and hospice on Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives, was built several years after the 1898 visit of the empress and her husband. The building, dedicated to Augusta Victoria and named after her, was inaugurated in 1910. In Abady’s image (Augusta Victoria I) the compound looks somewhat reduced in size, recalling a building in European folk tales, both in size and status: it is less like a church than a large inn that has lost its normal proportions. It sits, gloomy and semi-abandoned, but on the same yellowish desert background that locks it into a landscape to which it does not belong. The image diminishes the foreignness of the structure that was designed in the classical Germanic style, but it also blurs the Jerusalem stone of which it is built, thus marking the building as not belonging in the landscape in which it is planted. In another image (Augusta Victoria III, which does not appear here) Abady places an olive tree next to the mausoleum in which Augusta Victoria is buried, situating it in a kind of wilderness that is very different from its actual place in the Antique Temple in Sanssouci Park, Potsdam. The works in the series are etched on OSB (oriented strand board), which serves as particle board in Germany. The boards are made of pressed, layered strands or flakes of wood, which create an impression of captive, frozen chaos. Apart from the use of white, a color that here symbolizes death—a motif that recurs in these works—there is almost no use of color in the series. The other dominant colors are black, which results from etching, and yellow, the original color of the OSB. The etching-scorching technique signifies and symbolizes the region and the flaming, burning sun that is so characteristic of the Land of Israel and the surrounding region yet so foreign to Germany. Thus the German material, the substrate, creates a landscape and temperament that are characteristic of the region of Palestine/the Land of Israel. During his visit the kaiser inaugurated the Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem and received from the Ottoman sultan the land on which the Dormition Abbey stands. One may think of these two buildings and the Augusta Victoria compound as properties in a colonialist game of Monopoly played in this region by kings and emperors. And indeed, the Augusta Victoria compound changed hands several times. At the beginning of World War I, for example, the hospice became the chief Turko-German headquarters in Jerusalem and a military hospital. In 1917, after the British conquest, the building became the chief British headquarters in the Land of Israel, and with the beginning of the British mandate (1920), it housed British government institutions. In 1949 the compound fell into Jordanian hands, and in 1967 it fell into Israeli hands. In municipal terms the Augusta Victoria compound is part of Jerusalem, but one sees the desert from it. In this sense the compound is symbolic of the stereotype of culture and progress as opposed to the primitiveness of the past—of civilization’s conquest of the wild. Abady’s series also tells of lingering colonialism—and again the individual case, this time of the compound, is a manifestation of the broader and more general process whose main players at the moment are the current inhabitants of the region. Nevertheless, and despite the minimalism of the images, the series expresses colonialism that is not only local.

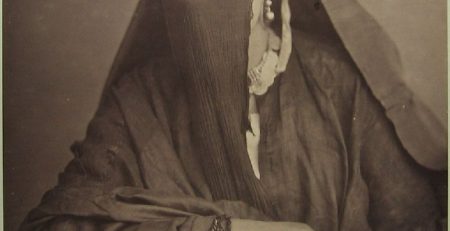

After the dismantling of the empire in 1918, Augusta Victoria fled into exile in Holland along with Wilhelm II, and there she died. The image of her daughter, Victoria Louise, as a Muslim woman is based on the garment she wore at the funeral of her mother, Augusta Victoria, in Potsdam: a black cape and a black veil covering her head, a kind of burka. In the film of the funeral she stands out in her strangeness—belonging and not belonging—her body hidden in black as if it were drawn to the funeral procession from a totally different place. Indeed, the series deals with the “there” and the “here,” with fate, history, and politics, but Victoria Louise’s appearance creates a clear connection to the Muslim and Palestinian space in the region. In my mind’s eye I see the portrait (Augusta Victoria I) of the exiled empress as connected—by means of the background—to the picture of the compound named after her. It is that same compound that belongs and does not belong. Abady’s image portrays it as a compound in exile; in reality it looks like a wing hacked off the Hohenzollern Castle (another image in this series, which does not appear here) and parachuted into the region. Augusta Victoria’s hairline in the image is not clear, and therefore one may imagine the compound as existing within her head, symbolizing her brain entrenched in sorrow over her son who has committed suicide. And the black hatching under the compound echoes the steps of Victoria Louise, as if she were making a getaway, dressed in black.

Shy Abady, Augusta Victoria I, 2010, Electric etching and oil on OSB, 120x130cm. Copyright Abady.

III

Above I suggested that Abady presents us with an alternative historico-politicocultural picture. In a certain sense the alternative in Abady’s images appears indirectly, but in another sense it appears directly, precisely by means of absence—the absence of Palestinians from the images in the series. The real history, both imagined and not imagined, simply happens. The Prussian Hohenzollern dynasty, to which Kaiser Wilhelm II belonged, lived in a world that was changing at breakneck speed, and its status in the world had declined in a manner and at a speed that its leaders apparently had not foreseen. From the series it appears very possible that the State of Israel, and perhaps other countries in the region, is now in a situation that is analogous to that of the empire during the period of Wilhelm II and that it does not understand how quickly history can change. Only two of the portraits in the series have clearly defined eyes that also look directly at the viewer: that of Hans, which is not printed here, and that of Augusta Victoria. Herzl appears to be looking off into the future, but whom does he not see, above whom is he gazing? Who is that, really, beneath the black clothes? Is it indeed Victoria Louise, who sees but is not seen, perhaps by choice? Who was trampled under the hoofs of the galloping horse whose eyes are also quite dim? And in other images that do not appear here, the gazes are also unclear. Whom do Joachim’s pupilless eyes not see? Kaiser Wilhelm in his old age looks, forlorn, at a point outside the image, perhaps at the past. In another image, the kaiser’s oldest grandson, Wilhelm von Preussen, who was to have inherited the title but was killed during the German invasion of France in World War II, seems to be looking at the viewer, his eyes faded; one can only imagine them. This axis of the series generates growing tension, arousing a sense of something not talked about, and spreads an odor of intrigue both private and international—harbingers of catastrophe. The abstract image that concludes the series (The End) looks like magic or sorcery, a suggestion of which can also be found in the image of the horse, whose face mask gives it a dark, medieval appearance. This final image generates a feeling of fluttering: the black color looks as though it is in constant motion, as if it has the potential to become a black hole. Here is sorcery that is able to suck whole worlds into itself but that also has the power to create worlds with the wave of a magic wand. In other words, this conclusion need not be final; it also symbolizes possibilities or alternatives. It can be a new beginning; it can bring forth out of itself new images and new presences. In an interview I conducted with Abady, he said: “We, the Jews of the State of Israel, live with the consciousness of a pogrom.” And indeed, despite the subject matter of the Augusta Victoria series—which is also based on the optimistic vision of Herzl regarding the Jewish state, a vision that is ultimately based on a pessimistic view of the condition of the Jews—this series offers very limited hope. In this context one must note that this is not a happy series. Abady added: “This series, Augusta Victoria, is history and not history. The posttraumatic state that is etched in our Jewish DNA due to the Holocaust overtakes us and keeps us from conducting a true dialogue with the Levantine space. We keep waiting for the next catastrophe.” These words arouse in me a thought that is not at all simple: in a certain sense the realization of Herzl’s vision regarding the state of the Jews is a kind of photomontage.

Shy Abady, Victoria Louise, 2010, Electric etching and oil on OSB, 120x130cm. Copyright Abady.

Notes

[1] David Fogel, “On Autumn Nights” (1923), trans. Chana Kronfeld and Eric Zakim in Chana Kronfeld, On the Margins of Modernism: Decentering Literary Dynamics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 191–192.

[2] The series Augusta Victoria was exhibited at the Dan Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel (2012). Curator: Ravit Harari. For the entire series, see http://www.shyabady.net/en/node/221. Photographer: Yodan Abadi.

[3] Beyond this, there is an anecdotal similarity between the two: Herzl’s face is very similar to the face in Michelangelo’s sculpture Moses.

[4] As Gurevitch and Aran put it, “Even for the native-born, it [the Land of Israel] continues to remain a desire rather than a reality, a goal toward which to strive.” Zali Gurevitch and Gideon Aran, “The Land of Israel: Myth and Phenomenon,” Studies in Contemporary Jewry 10 (1994): 200.

- + About the Artist

-

Shy Abady (1965) was born and grew up in Jerusalem and now lives and works in Tel Aviv. He is a graduate of the Beit Berl School of Art (Hamidrasha) and is completing a master’s degree in art history at Tel Aviv University. Abady has created several series in which the central axis is biographical, tracing the lives of figures such as Vaslav Nijinsky, Hannah Arendt, and the poet Radu Klapper. In Berlin, between 2007 and 2008, he created the series titled My Other Germany, which moves along the historical-political axis while focusing on German sculptures and memorials. In addition to Abady’s drawings and paintings, a large part of his work in recent years has been based on techniques involving electrical etching on wood.

Since 1995 Abady’s works have been exhibited in one-man and group shows in Israel and abroad. Among his one-man exhibitions in recent years are The Hannah Arendt Project (2005: The Jewish Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; 2006: Jerusalem Artists’ House, Israel; 2010: Beit Hatfutsot, Tel Aviv, Israel); The Revolution that Danced (2009: Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center, Israel); Radu (2012: Zadik Gallery, Jaffa, Israel); and Augusta Victoria (2012: Dan Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel).

In 2000 Abady received a fellowship at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, sponsored by the Council for Culture and Art. In 2011 he received the Israeli national lottery (Mifal Ha-Payis) support fellowship to produce the catalog for the Radu series.

To see more photos from the series, see Abady’s website here.

- + Analysis

-

On the Photomontage

by Zohar Kohavi

In the black distance

gallops are sown of unseen horses

that are melting away. [1]

Shy Abady’s Augusta Victoria series, six of whose thirteen images are presented here, focuses on two families: that of Binyamin Ze’ev (Theodor) Herzl (1860–1904), visionary of the Jewish state, and that of the last German emperor and empress, Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941), and his wife, Augusta Victoria (1858–1921).[2] Abady focuses on the interaction between Herzl and Wilhelm II, relating to the fates of their two families as an allegory of the fates of the Jewish and German peoples, as well as that of the Palestinian people. The use of first names for many of the titles (Theodor, Victoria Louise, Joachim, Hans, Augusta Victoria, Wilhelm) suggests that the personal may be used to peruse the public: the portraits of individuals highlight the individual as the bearer of the political, and through this ensemble one sees the line that links the past to the present, and perhaps even to the future, like a pair of compasses moving in widening circles. Indeed, one of the motifs in this series is a line—a line that not only connects the works to each other but also expresses the connection the series makes between history, fate, and private and public worlds, linking them to our time while hinting at the posttraumatic nature of the present. Both families suffered similar tragedies, some of which are expressed in the series. For example, Hans, Herzl’s son, shot himself to death, as did Joachim, the son of Augusta Victoria and Wilhelm II. Through these two families Abady pinpoints coordinates, like dots that we must connect in order to see the historicopolitico-cultural picture. Alongside it—in a manner analogous to that of a hologram that shows the next possible move—he offers an alternative to that picture: the promise, either real or imagined, that lay in the meeting between Herzl and the kaiser. What would have happened, for example, if the kaiser had chosen to help Herzl establish the state of the Jews at the end of the nineteenth century? And if he had helped, what would the Judeo-Palestinian space look like today?

I

Herzl, the father of political Zionism and the founder of Zionism as an institutionalized movement, was born in Budapest. When he was eighteen he moved with his family to Vienna, where he completed his law studies and worked in journalism and as a writer of prose and plays. As part of his efforts to realize his vision of a Jewish state, Herzl sought Wilhelm II’s help in influencing the Ottoman Sultan to grant a charter for Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel. He finally succeeded in obtaining a brief audience with the kaiser in Constantinople, and they had two more meetings in 1898 in the Land of Israel: one near Mikve Israel and the other in Jerusalem. These meetings, however, were a disappointment; it became clear that the kaiser, having learned of the sultan’s opposition to the idea, was no longer willing to try to influence him. The photograph on which the image Theodor is based is the documentation of Herzl’s meeting with Wilhelm II near Mikve Israel in October 1898. It became apparent during the development process that the photograph taken by David Wolfson was unusable, and therefore the meeting had to be documented by photomontage. Herzl was photographed again, this time on his own, in Jaffa. And that was how the picture familiar today was assembled. In a manner not lacking in symbolism, for the purposes of the photomontage the kaiser’s image, captured by the original photograph, was transferred from the white horse on which he had been riding to the black horse that had been standing behind it. A hint of this assemblage is evident in the image of the black horse (The Horse), whose head is covered by a white mask. One might say that Herzl is the modern incarnation of the biblical Moses. Moses led the Israelites to the land of Canaan, and to that end he negotiated with the pharaoh; Herzl negotiated with the kaiser, and other rulers, to promote a similar, perhaps even identical, idea. Both brought the Jewish people to where it lives today, and both, despite the task they had taken upon themselves, were in some sense outsiders; perhaps that is why neither of them was privileged to enter the Promised Land. Moses was not privileged to enter the Land of Israel in the physical sense, and Herzl was not privileged to enter in the political sense.[3] Like Moses’s efforts to bring the Israelites to Canaan, Herzl’s were somewhat surprising—a kind of improvisation that did not appear in the original script. The tension embodied in Herzl the private person corresponds to the foreign, ambivalent affiliation of the Jewish people with this place. Herzl was a Jew who, until he covered the Dreyfus trial, was assimilated and secular—but with the appearance of a semi-ultraOrthodox Jew—and a European who strove to reach the Land of Israel. Like Herzl and the kaiser—who met in Mikve Israel, but whose meeting was memorialized in a semi-artificial way—the Israelites lived in this region as authentic natives but are here today in a semi-artificial way: belonging and not belonging. Coming home is an understandable longing, but sometimes it seems that it is perfect only as a desire—that is, as long as it is not realized. [4] In a certain sense the return of the Jews to their land is comparable to the return of the adult to his parents’ house. One cannot defeat the laws of nature; in his parents’ house he becomes a child and must grow up again.

Shy Abady, Theodor, 2010, Electric etching and oil on OSB, 120x130cm. Copyright Abady.

II

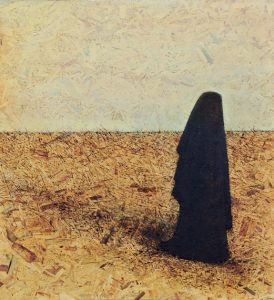

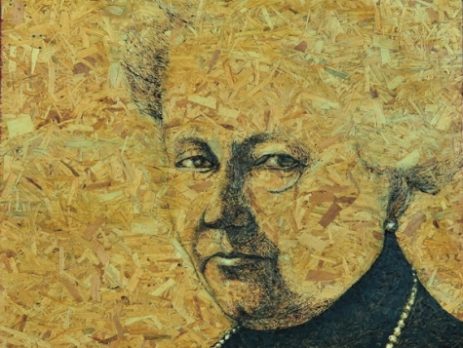

Augusta Victoria, the church and hospice on Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives, was built several years after the 1898 visit of the empress and her husband. The building, dedicated to Augusta Victoria and named after her, was inaugurated in 1910. In Abady’s image (Augusta Victoria I) the compound looks somewhat reduced in size, recalling a building in European folk tales, both in size and status: it is less like a church than a large inn that has lost its normal proportions. It sits, gloomy and semi-abandoned, but on the same yellowish desert background that locks it into a landscape to which it does not belong. The image diminishes the foreignness of the structure that was designed in the classical Germanic style, but it also blurs the Jerusalem stone of which it is built, thus marking the building as not belonging in the landscape in which it is planted. In another image (Augusta Victoria III, which does not appear here) Abady places an olive tree next to the mausoleum in which Augusta Victoria is buried, situating it in a kind of wilderness that is very different from its actual place in the Antique Temple in Sanssouci Park, Potsdam. The works in the series are etched on OSB (oriented strand board), which serves as particle board in Germany. The boards are made of pressed, layered strands or flakes of wood, which create an impression of captive, frozen chaos. Apart from the use of white, a color that here symbolizes death—a motif that recurs in these works—there is almost no use of color in the series. The other dominant colors are black, which results from etching, and yellow, the original color of the OSB. The etching-scorching technique signifies and symbolizes the region and the flaming, burning sun that is so characteristic of the Land of Israel and the surrounding region yet so foreign to Germany. Thus the German material, the substrate, creates a landscape and temperament that are characteristic of the region of Palestine/the Land of Israel. During his visit the kaiser inaugurated the Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem and received from the Ottoman sultan the land on which the Dormition Abbey stands. One may think of these two buildings and the Augusta Victoria compound as properties in a colonialist game of Monopoly played in this region by kings and emperors. And indeed, the Augusta Victoria compound changed hands several times. At the beginning of World War I, for example, the hospice became the chief Turko-German headquarters in Jerusalem and a military hospital. In 1917, after the British conquest, the building became the chief British headquarters in the Land of Israel, and with the beginning of the British mandate (1920), it housed British government institutions. In 1949 the compound fell into Jordanian hands, and in 1967 it fell into Israeli hands. In municipal terms the Augusta Victoria compound is part of Jerusalem, but one sees the desert from it. In this sense the compound is symbolic of the stereotype of culture and progress as opposed to the primitiveness of the past—of civilization’s conquest of the wild. Abady’s series also tells of lingering colonialism—and again the individual case, this time of the compound, is a manifestation of the broader and more general process whose main players at the moment are the current inhabitants of the region. Nevertheless, and despite the minimalism of the images, the series expresses colonialism that is not only local.

After the dismantling of the empire in 1918, Augusta Victoria fled into exile in Holland along with Wilhelm II, and there she died. The image of her daughter, Victoria Louise, as a Muslim woman is based on the garment she wore at the funeral of her mother, Augusta Victoria, in Potsdam: a black cape and a black veil covering her head, a kind of burka. In the film of the funeral she stands out in her strangeness—belonging and not belonging—her body hidden in black as if it were drawn to the funeral procession from a totally different place. Indeed, the series deals with the “there” and the “here,” with fate, history, and politics, but Victoria Louise’s appearance creates a clear connection to the Muslim and Palestinian space in the region. In my mind’s eye I see the portrait (Augusta Victoria I) of the exiled empress as connected—by means of the background—to the picture of the compound named after her. It is that same compound that belongs and does not belong. Abady’s image portrays it as a compound in exile; in reality it looks like a wing hacked off the Hohenzollern Castle (another image in this series, which does not appear here) and parachuted into the region. Augusta Victoria’s hairline in the image is not clear, and therefore one may imagine the compound as existing within her head, symbolizing her brain entrenched in sorrow over her son who has committed suicide. And the black hatching under the compound echoes the steps of Victoria Louise, as if she were making a getaway, dressed in black.

Shy Abady, Augusta Victoria I, 2010, Electric etching and oil on OSB, 120x130cm. Copyright Abady.

III

Above I suggested that Abady presents us with an alternative historico-politicocultural picture. In a certain sense the alternative in Abady’s images appears indirectly, but in another sense it appears directly, precisely by means of absence—the absence of Palestinians from the images in the series. The real history, both imagined and not imagined, simply happens. The Prussian Hohenzollern dynasty, to which Kaiser Wilhelm II belonged, lived in a world that was changing at breakneck speed, and its status in the world had declined in a manner and at a speed that its leaders apparently had not foreseen. From the series it appears very possible that the State of Israel, and perhaps other countries in the region, is now in a situation that is analogous to that of the empire during the period of Wilhelm II and that it does not understand how quickly history can change. Only two of the portraits in the series have clearly defined eyes that also look directly at the viewer: that of Hans, which is not printed here, and that of Augusta Victoria. Herzl appears to be looking off into the future, but whom does he not see, above whom is he gazing? Who is that, really, beneath the black clothes? Is it indeed Victoria Louise, who sees but is not seen, perhaps by choice? Who was trampled under the hoofs of the galloping horse whose eyes are also quite dim? And in other images that do not appear here, the gazes are also unclear. Whom do Joachim’s pupilless eyes not see? Kaiser Wilhelm in his old age looks, forlorn, at a point outside the image, perhaps at the past. In another image, the kaiser’s oldest grandson, Wilhelm von Preussen, who was to have inherited the title but was killed during the German invasion of France in World War II, seems to be looking at the viewer, his eyes faded; one can only imagine them. This axis of the series generates growing tension, arousing a sense of something not talked about, and spreads an odor of intrigue both private and international—harbingers of catastrophe. The abstract image that concludes the series (The End) looks like magic or sorcery, a suggestion of which can also be found in the image of the horse, whose face mask gives it a dark, medieval appearance. This final image generates a feeling of fluttering: the black color looks as though it is in constant motion, as if it has the potential to become a black hole. Here is sorcery that is able to suck whole worlds into itself but that also has the power to create worlds with the wave of a magic wand. In other words, this conclusion need not be final; it also symbolizes possibilities or alternatives. It can be a new beginning; it can bring forth out of itself new images and new presences. In an interview I conducted with Abady, he said: “We, the Jews of the State of Israel, live with the consciousness of a pogrom.” And indeed, despite the subject matter of the Augusta Victoria series—which is also based on the optimistic vision of Herzl regarding the Jewish state, a vision that is ultimately based on a pessimistic view of the condition of the Jews—this series offers very limited hope. In this context one must note that this is not a happy series. Abady added: “This series, Augusta Victoria, is history and not history. The posttraumatic state that is etched in our Jewish DNA due to the Holocaust overtakes us and keeps us from conducting a true dialogue with the Levantine space. We keep waiting for the next catastrophe.” These words arouse in me a thought that is not at all simple: in a certain sense the realization of Herzl’s vision regarding the state of the Jews is a kind of photomontage.

Shy Abady, Victoria Louise, 2010, Electric etching and oil on OSB, 120x130cm. Copyright Abady.

Notes

[1] David Fogel, “On Autumn Nights” (1923), trans. Chana Kronfeld and Eric Zakim in Chana Kronfeld, On the Margins of Modernism: Decentering Literary Dynamics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 191–192.

[2] The series Augusta Victoria was exhibited at the Dan Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel (2012). Curator: Ravit Harari. For the entire series, see http://www.shyabady.net/en/node/221. Photographer: Yodan Abadi.

[3] Beyond this, there is an anecdotal similarity between the two: Herzl’s face is very similar to the face in Michelangelo’s sculpture Moses.

[4] As Gurevitch and Aran put it, “Even for the native-born, it [the Land of Israel] continues to remain a desire rather than a reality, a goal toward which to strive.” Zali Gurevitch and Gideon Aran, “The Land of Israel: Myth and Phenomenon,” Studies in Contemporary Jewry 10 (1994): 200.

Leave a Reply