-

Add to cartQuick view

Add to cartQuick viewGender, Religion, and Secularism in the English Mission Hospital of Jerusalem, 1844–1880

Free!This article offers new insights into the operation of the Mission Hospital built in Jerusalem in 1844 by the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews (LJS) and the space that was created within it. I argue that the encounter in Jerusalem between Jewish women and the missionaries worked to create a liminal space that was neither religious nor secular, neither Jewish nor Christian, but all (and none) of these at once. I draw on Olwen Hufton’s concept of the “economy of makeshifts” to portray the hospital’s unique space. Based on the existing literature and new evidence, I show that in effect the Mission Hospital served women more than men, and I suggest that the gender composition of the patients allowed the hospital to succeed and helped to shape its operation. After a brief review of the literature, I introduce the LJS and compare its Jerusalem medical mission with contemporary medical institutions in England. I then expand on evidence showing that the Mission Hospital was in fact more of a women’s hospital and suggest why that was the case.

Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

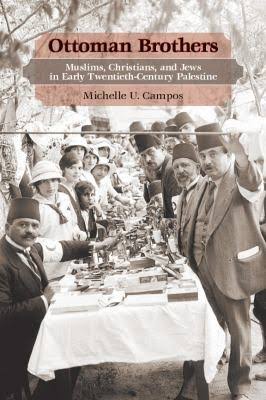

Michelle U. Campos. Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011. 360 pp.

Michelle U. Campos. Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011. 360 pp.

$5.00Free!Add to cartQuick view -

Add to cartQuick view

A Center of Transnational Syriac Orthodoxy: St. Mark’s Convent in Jerusalem

Free!This article highlights the role of St. Mark’s Convent in Jerusalem as a center of transnational Syriac Orthodoxy. Beginning with Manuel Vásquez’s discussions of transnational religion, it underlines the processual aspect of the transnationalism that characterizes contemporary Syriac Orthodoxy in the Holy Land, as it emerged from a mixture of pilgrimage, genocide, and diaspora as well as the combined forces of ecclesiastical expansion and changing political contexts. A complex web of relationships thus connects the community of Jerusalem to the other Syriac Orthodox groups in Bethlehem and Jordan, to the Syriac Orthodox center in Damascus and Ma‘arat Saydnaya, to the monasteries in Tur Abdin, to the faithful in India, and to the many communities in the diasporas of Europe, the Americas, and Australia. In Jerusalem this network is maintained by a narrative expressed in texts and images that combines the ancient connection to the holy places with the nationalist narrative of the lost homeland, brought together in the profuse use of Classical Syriac, the symbolic language of both church and nation.

While this community in many ways resembles the other small orthodox churches of the Holy Land, especially the Armenian and Ethiopian churches—whose members, like the Syriac Orthodox, tend to see themselves as ethnically different from the majority of local Christians—the Syriac Orthodox differ in that their homeland is a virtual one, existing primarily in the transnational network that ties all the different locations together. In the creation of this virtual homeland, Jerusalem plays a crucial role as the least political, most ecumenical, and most international of all current Syriac Orthodox centers.

Add to cartQuick view

- Home

- About JLS

- Issues

- Vol. 9 No. 1 | Summer 2019

- Vol 8 No 2 Winter 2018

- Vol. 8, No. 1: Summer 2018

- Vol. 7, No. 2: Winter 2017

- Vol. 7, 1: Summer 2017

- Vol. 6, Summer/Winter 2016

- Vol. 5, No. 2 Winter 2015

- Vol. 5, No. 1 Summer 2015

- Vol. 4, No. 2 Winter 2014

- Vol. 4, No. 1 Summer 2014

- Vol. 3, No. 2 Winter 2013

- Vol. 3, No. 1 Summer 2013

- Vol. 2, No. 2 Winter 2012

- Vol. 2, No. 1 Summer 2012

- Vol. 1, No. 2 Winter 2011

- Vol. 1, No. 1 Summer 2011

- Blog

- dock-uments

- Subscribe

- Submit

- Contact